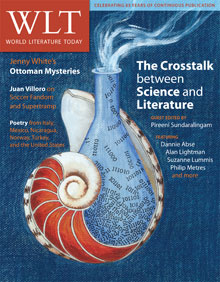

Bridging the Two Cultures: A Conversation between Alan Lightman and Rebecca Newberger Goldstein

In their recent exchange, physicist Alan Lightman and philosopher Rebecca Newberger Goldstein reflected on “thinking and feeling our ways beyond what we can know,” and how they devise “emotional experiments” in their fiction in order to probe the limits of rational thought.

Dear Alan,

I want to thank you, first of all, for allowing this conversation to take place electronically, a form of communication that I know you have some serious qualms about. You’re as averse to it as I am to the telephone. (I hate the telephone because it doesn’t allow for long periods of silence. If one is quiet for too long, the other person invariably asks, “Are you still there?”)

I thought I’d start off by asking the fairly obvious question centered on a similarity between us. We’ve both had what some might consider “irregular” writing careers, as we both started as academics in somewhat technical areas—you in physics and cosmology, me in analytic philosophy, with a concentration in philosophy of science—and only switched to writing after we’d earned our credentials in those other fields. Was this always your plan, or have you found yourself surprised by the turn your career has taken?

I have to confess that, in my own case, the literary turn took me somewhat by surprise. I’ve always loved literature—it’s almost a physical need for me to gorge myself regularly on fiction and poetry—but I never planned on this passion shaping my career until I found myself . . . well, writing a novel, almost in a trance. Looking back, I see how I might have been preparing to be a novelist with all that gorging, but I certainly wasn’t conscious of any literary intentions until the voice of a character announced herself to me in the first sentence of my first book: “I’m often asked what it’s like to be married to a genius.” It was what Henry James called a donnée, and I accepted it as that and just sat down and wrote the novel, The Mind-Body Problem. I have so say, none of my other books, neither fiction nor nonfiction, ever arrived in quite the same peremptory way.

Tell me about your experience in broadening out into fiction. Have you always been aware that both science and literature were paths you would follow? Were you surprised to find yourself writing the extraordinaryEinstein’s Dreams?

With eager anticipation,

Rebecca

*

Dear Rebecca,

It will be a delight for me to talk about our careers together, although I wish that the conversation were in person. I understand that you are traveling a lot now, and this e-form is the only way possible.

I was both surprised and not surprised about the blooming of my literary career. Since a young age, I did have a passion for both the sciences and the arts. I built rockets and gadgets and looked at things under my microscope. I created a small laboratory in a storage room next to my bedroom, where I kept various chemicals, Bunsen burners, test tubes, batteries, and electrical wire, resistors and capacitors, etc. I also loved to read, and I wrote poetry. Poetry was my first writing form. Almost none of the poetry I wrote at that age (8–16) was worth anything, but it was a vehicle for expressing my emotions and my thoughts. I was philosophical from a young age (as I am sure you were) and wrote poems about death and the puzzle of existence as well as odes to thirteen-year-old girls I was in infatuated with. I also loved the meter and sound of poetry. I loved the sound of interesting words.

My friends separated clearly into two groups: the “artists” (intuitive, spontaneous, etc.) and the “scientists” (logical, deliberate, etc.). I passed between the two groups of friends (who did not mix with each other) easily and found myself behaving like an “artist” when I was with my artist friends and like a “scientist” when I was with my scientist friends. So, I knew very well that I had these two different capacities and interests, and that the combination of the two was unusual. My friends, parents, and teachers did not exactly discourage my dual capacities, but they made it clear that life would be easier for me if I went in one direction or the other, not both. I had no role models for people who were both scientists and artists, although in high school I became aware of C. P. Snow, and I read some of Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring and realized, “Hey, here is a scientist who can write in a literary form.”

I am not sure that I had a clear idea of exactly what career I wanted to pursue, but I did not want to give up my “dual capacities.” At some point, it became a practical matter. I had to choose a major. I knew of a few scientists who later became writers (Snow, Carson) but no artists who later in life became scientists, so without understanding the basis for this fact but just accepting it, I majored in physics (at Prince-ton). However, I took lots of courses in literature, philosophy, etc., and even a studio class in sculpture with the prominent Princeton sculptor Joe Brown. Again, as a practical matter, I went to graduate school in physics (Caltech), but even there I took some courses in philosophy. At this point, I was publishing poetry in small literary magazines. I did not start spending a lot of time writing until around 1980, six years after my PhD and after I had a secure job in science (at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics). At this point, I began writing essays about science for a magazine called Science 80, published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. (My first couple of essays about science had been published inSmithsonian magazine.) I found the essay a wonderful form of writing in which I could be informative, personal, philosophical, and poetic. I am still proud of some of those early essays. After a couple of years of this, I published a collection of my essays in book form and also published a couple of essays in the New Yorker. I was encouraged by William Shawn, the editor of the New Yorker, and by John McPhee, both of whom read my stuff. With that encouragement, I began to experiment with the essay, stretching its limits, adding fictional elements. Around 1991, shortly after moving from Harvard to MIT (where I had been given a joint position in science and humanities), I got the idea for Einstein’s Dreams, which was my first book of fiction. But as you can see, I arrived there in gradual steps. In fact, I had already published some stand-alone “fantasy” type essays that were not dissimilar from the chapters of Einstein’s Dreams. So, I was not so surprised to have arrived at that point, but I was extremely surprised (as was everyone) at the success of that book.

So, this is a very long answer to your question about whether I was surprised or not surprised by the onset of my literary career. I can add that I remember I was worried, in the early and mid-1980s, about whether my scientific colleagues would disapprove of my writing for the public. At that time, I was quite immersed in the scientific community, and there were very few practicing scientists who were writing for the public. Rachel Carson, Lewis Thomas, Stephen Jay Gould, and Loren Eiseley had not been writing for long at that time. In the scientific community, there was definitely an ethos that you were going soft if you wrote for the public instead of spending 100 percent of your time doing research. Of course, the situation today is much different. Now there are many practicing scientists who are also literary writers, and they are celebrated. But in the early and mid-1980s, when I started, there were only a few. I remember that I had lunch with Stephen Jay Gould once in the mid-1980s, and we talked about just this issue.

With much appreciation and affection,

Alan

*

Dear Alan,

You seem to have been far more clearheaded about plans for your future than I. I just seem to have bumbled my way unwittingly. I suspect this had something to do with my being raised in a very religious household. The idea of a girl having any large plans for her future was unthinkable, and I never learned the art of cultivating personal ambitions. I’ve just been led along, almost blindly, by the things I’m interested in.

And, like you, my tendencies showed themselves early. We were not very well-off in my family, and children’s books were far beyond our means. So every Friday afternoon, I was taken, along with my siblings, to the public library to get our Sabbath reading material, since we weren’t permitted to do much else other than read from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday. From the moment that I could read books for myself, I imposed a strict rule. On each weekly library visit, I would take out two books, one that I called a “good-for-me” book, which was always nonfiction, and the other that I called a “fun” book, which was always make-believe. And I wouldn’t allow myself to read the fun book until I had read the good-for-me book. So I think the lifelong pattern of loving but slightly dismissing fiction was there from the beginning.

It happened to be one of the good-for-me books that first lit my fire. It was a book about atoms, and it delivered the absolutely astounding news to me that the seemingly solid objects all around me were not as they seemed but were composed of little colorless bits whirring around in orderly ways through empty space. My six-year-old world was rocked! It seemed that the world as I saw it—including all the pretty colors I loved so much—weren’t “out there” in the objects at all, but were somehow due to the interaction between those whirring bits and me. How altogether changed the world became with this astonishing news. I remember just sort of walking around in a daze, thinking, “In here it’s like this, but out there it’s like . . . what?” This whole idea of an “in here” and “out there” just blew me away. I didn’t have anyone I could talk all this over with, of course, so I just kept reading whatever I could. There were people who knew what really was “out there,” and they were called “scientists.” Man, these scientists were something else! They seemed to be performing an almost unimaginable feat, getting outside of their own minds. How’d they do that? My awe with scientists didn’t make me want to be a scientist—as I said, I completely lacked the art of thinking about my own future—but I did want to learn about how they did the things they did, and maybe even to meet one of them in my lifetime and then ply him with questions. That was as far as my ambition at that time went. But as I got older I did want, quite ardently, to get out of the “in here” of my own insular world and “out there” to where knowledge about the great large world was being pursued.

When I got to college—Barnard College at Columbia University, and the great privilege of getting to go there was a saga in itself—I enjoyed my math and physics classes immensely, but found that it was the philosophy classes—most especially the epistemology and philosophy of science and philosophy of mathematics classes—that touched my interests the most deeply. I was still consumed with knowing how we manage to know the things we know, how we traversed the space between “in here” and “out there,” if indeed we did. And here’s a confession: I never took a single literature course, or art course of any sort, for that matter. I perpetuated my childhood bias that fiction was just fun, something I would allow myself to indulge in only after I’d put in the good hard work of mastering “real” knowledge. Perhaps because my education was nothing I could take for granted, I felt I couldn’t squander it on studying things that gave me nothing but drunken joy.

I went on to Princeton, after I graduated Barnard, and got a PhD in philosophy. Not so surprisingly, given my childhood obsession with the “in here” and the “out there,” my dissertation topic was on what we now call “the hard problem of consciousness,” though at that time we simply referred to it as “the mind-body problem.” I’d come to Princeton thinking I would do hard-core philosophy of science—foundations of quantum mechanics, perhaps—but I got rather seduced by Tom Nagel’s seminal paper “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” and decided to work with him (he was then at Princeton). Very little did I ever dream that, within a few years of getting my doctorate and a desirable job, I would publish a novel—a novel, of all things!—calledThe Mind-Body Problem. I still hadn’t learned how to think ambitiously about my own future, or I never would have dared to do it. I would have realized that publishing a novel was not the sort of thing for a very young woman in a male-dominated field to do if she wished to be taken seriously by her colleagues. Perhaps only someone from my insular background could manage to be as clueless as I’ve managed to be.

I’ve brought up my religious past, and that brings me to the next question I’d love to ask you, one which concerns another surprising parallel between our two careers. Both you and I have recently published works that explore the fraught space between—to put it somewhat crudely—reason and faith. Your novel, Ghost, concerns a person who perhaps has a supernatural experience, one that he himself is not altogether ready to believe in, and the way in which this ambiguous experience gets co-opted by others. My novel 36 Arguments for the Existence of God: A Work of Fiction is focused on the contemporary debate between science and religion. My protagonist, Cass Seltzer, is a psychologist of religion who has published a runaway atheist best-seller and become a poster boy for secularism, but he, too, has a tendency toward transcendent experience and gets dubbed “the atheist with a soul.”

I suspect that, if asked to place yourself on one side of the reason/faith divide, you, like me, would go stand over with the reason people; and yet we both, I think, have a tendency to see “the other side” with some sympathy, to perhaps tolerate more ambiguity and conflict in this area than others of our rationalist persuasion do. Is that why you felt compelled to write a novel on the subject, because of what a novel can encompass when it comes to human dilemmas concerning the limits of human understanding? And while you’re at it, perhaps you could address this general question of what the novel can encompass that other forms of writing can’t. What determines you to write a novel—or, for that matter, in your case, a poem—about a particular intellectual theme or dilemma, rather than an essay or a nonfiction book?

Warmest wishes,

Rebecca

*

Dear Rebecca,

If I may attempt to answer the second question first: Why write about ideas and intellectual themes in fiction rather than in nonfiction? First of all, I would argue that as far as human beings are concerned, there are no purely intellectual themes. Everything we care about has an emotional dimension. I am far from an expert on the brain, but the amygdala, the part of our brain that deals with emotions, is a very primitive organ created millions of years ago for survival, and it is probably involved at some level with every thought we have, whether we like it or not. Homo sapiens has evolved a lot intellectually, but not much emotionally. Look at all the judges and senators and generals who throw their professional careers away for extramarital affairs. If you want a person to really care about something, intellectual or not, you need to hit him or her in the amygdala. Reading a novel is a far different experience from reading a book on history or astrophysics or, dare I say, philosophy. When we read a novel, we are taken to the scene, we smell the scent of linseed oil, we hear the cracking voice of a grandfather, we see the smoke rising from a burning house in the distance. We feel the joy and suffering of good characters. Either consciously or unconsciously, we enter the world created by the novelist and experience things at a visceral level. Words and actions and scenes make an emotional impression on us, and that impression is deep. Nonfiction, of course, is extremely important in its own right, and has its own advantages, and there are some readers who wouldn’t touch fiction with a ten-foot-thick dictionary. In nonfiction, we can give the reader lots of facts and even understanding of the facts. (I believe that Harold Ross, the first editor of the New Yorker, said, “I never met a fact I didn’t like.”) But if we want to get deep inside the primitive brain of our reader (and in her skin and blood as well), fiction has its advantages. When I began working on the book that eventually became my novel The Diagnosis, which, roughly speaking, is about the American obsession with money, speed, and information, I first outlined a nonfiction book like Jonathan Schell’s Fate of the Earth. I actually wrote a number of factual chapters about the subject, documenting such things as consumption, productivity, loss of leisure time, etc. Then, halfway through, I realized that what I was really after was a mentality, a way of living in the world, a bankruptcy of the spirit. I decided that these psychological issues would be better treated in novelistic form. In fiction, I could make the reader feel the frenzy of modern life in America and get inside the head of a particular victim of that frenzy.

Now turning to your second question: Why did I use fiction as a way to write about the divide between science and religion? Why not just discuss the two different approaches to the world, their celebrated histories, perhaps give a few case studies, give the pluses and minuses of each worldview, and finally come down on one side or the other? First of all, I feel that science and religion are the two greatest forces that have shaped civilization as we know it. Whatever one’s view as to which should have the upper hand, one cannot dismiss one endeavor or the other (as Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and others have done). Instead, one should try to understand why each worldview has been so powerful. Personally, I certainly endorse the scientific worldview as a necessary way of understanding the physical universe. But I also believe that there are realms of thought and interesting questions beyond the reach of science, such as “What is the nature of love?” or “Is it right to kill other human beings in war?” Personally, I do not believe that an intelligent being created the universe. But science can never disprove that assertion. After reading a great work like William James’s Varieties of Religious Experience, a thinking person must acknowledge that religion satisfies deep emotional and psychological needs that we all have. In Ghost, I wanted to explore and try to understand better those needs. I started with a rational kind of person and subjected him to an irrational, “supernatural” experience. What would he make of such an experience? Would he deny it? Or would he desperately try to explain it away, to find some rational explanation of irrational events? Or would he alter his worldview? As my main character reacts to the experience and evolves, he goes through all of these phases. I wanted to both understand and convey to the reader a largely emotional experience, a grueling and psychologically tumultuous reexamination of one’s understanding of the nature of things. How could I do better than have the reader herself involved emotionally with the text—namely, portray the narrative in novelistic form, with all the techniques available to the novelist? In a way, this novel, and many novels, are like emotional experiments. You put your characters in a difficult situation, and you see how they will react. You, the writer, should not figure out their reaction in advance. You should not work out the plot in advance. If you do, it is not an honest experiment. It is a prejudged experiment, like the physicists who measured the wrong number for the speed of light for decades because they thought they knew what the number should be, so they kept kicking the equipment until it gave the number they were expecting. You, the writer, should, after putting your characters in a difficult situation, stand back and wait and listen, and eventually your characters will react in an authentic and sometimes surprising way. It is always good when a character surprises the writer, because then you know you have done an honest experiment and found out something new. I have never had a supernatural experience myself, but I wanted to know how a person such as myself might react to such an experience, so I created the experiment in the novel. And I got a deeper understanding of what the religious experience is all about. I hope that I conveyed some of that understanding to the reader.

Thank you for your excellent questions and comments so far. I can't wait to see what else you have up your sleeve.

Dear Alan,

My sleeves are large when it comes to producing topics that you and I could profitably discuss together, but I think the readers of this journal might be reaching the limits of any desire they have to eavesdrop on us, so perhaps we ought to wind down.

I would like to add something to your comments about the ways in which the intellectual and the emotional aspects of our beings interpenetrate each other, since for me this is a large topic, the heart of why I’ve felt driven to resort so often to fiction.

The reason I love fiction as a setting for thinking about the sort of issues that engage me is that fiction allows a way of doing justice to a fact that thinkers often ignore, namely that it’s not only our thinking selves that are brought to bear when we explore intellectual issues, but our feeling selves as well. I think this fact is particularly true in philosophy, precisely because philosophy casts us out into the tricky intellectual terrain of questions that appear to have answers—although sometimes this appearance is challenged, and sometimes successfully—but where the answers don’t seem to be forthcoming from all the empirical information at our disposal. In other words, given all that we presently know, both empirically and conceptually, it’s possible to hold vastly differing views on questions like free will, the mind-body problem, the grounds of morality, the existence of God, the nature of the a priori, the universe vs. the multiverse, and many other problems. In other words, these questions are, for us, with our specific evolutionally-endowed cognitive equipment and at this moment in our collective cognitive history, mysteries. We don’t have the means for answering them, so when we think about them—and most of us can’t help but think about at least a certain subset of them—our entire temperament, which is just as much emotional as it is intellectual, is brought into play.

There are lots of factors that go into these temperaments, including how we feel about the very fact of mystery in the first place. For some thinkers the notion of impenetrable mysteries is beckoning; they revel in it, and frame propositions about the world that only increase the mystery, which propositions sometimes get themselves expressed religiously and sometimes not. For others, mysteries are regrettable but undeniable; they put up with them and frame propositions about the world that accommodate themselves to it. For others, the idea of the incorrigibly mysterious is intolerable; it makes them break out into hives. They frame propositions about the world that deny all mysteries, either “domesticating” them by turning them into empirical or conceptual problems, or by trying to eliminate them as pseudo-problems, thereby banishing them from the conversation.

These differing reactions to the whole idea of the mysterious are only one of the many variables that go into making up our temperament, our point of view, our character; and one of the things I love about fiction is that we’re allowed to show the play of temperament in our thinking, as well as our feeling, lives. The sort of fiction I love, both to read and to write, works to subvert the distinction that people often draw between the intellect, on the one hand, and the passions on the other. You can’t get away with that false dichotomy if you’re going to write about intellectual themes in fiction. You have to embed themes, no matter how abstract, in the emotional substance of your characters and your plot, and that embedding seems to me to give a truer picture of what it is really like to try and make sense of this world, thinking and feeling our way out beyond what we can know.

I began this conversation by thanking you for generously conceding to this form of communication, and I thank you with even more gratitude now, since you’ve shared the profundity of your ideas and your personal history so generously. I know that you harbor serious skepticism about e-mail, and about many of the other forms of technology which you think encourage shallowness, a flattening and thinning of our inner lives. But would you agree with me that new technologies in communication can sometimes contribute to a deepening of awareness? I hope so, since I think that’s what we were both after in this electronic exchange.

But next time, I promise, we’ll have our meandering conversation across a table in a café in Cambridge, which is still probably the best way, just so long as my conversationalist isn’t driven crazy by my interminable silences.

Until then, with admiration and affection,

Rebecca

*

Dear Rebecca,

You wanted me to give a brief reply to your last question: Does technology sometimes enhance our communication and connection with each other? Certainly. I have always thought that technology, in and of itself, is neutral in values. It is how we human beings use technology that gives it value. Technology can be used for good and for ill. Let us limit ourselves to communication technology. When e-mails are used as the fast-food version of communication, then they don't have much value to me, and I get indigestion of the brain. Fast-food communications are thoughtless and time-wasting, and they lead to a mentality of superficiality. On the other hand, e-mail can be used to connect people who would otherwise not be able to communicate at all. E-mail can connect family and friends and lovers who have no access to telephones. E-mail allows me to direct my project for helping young women in Cambodia, twelve time zones away. So, yes, technology can be a good thing.

Thank you, Rebecca, for a most enjoyable conversation, all through e-mail. I love your thoughts and ideas. You are both a scientist and an artist.

October 2010