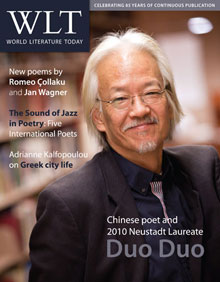

受奖辞

Translator's note: Duo Duo has always insisted that a poet should speak through his poetry instead of through any explanatory prose. Keeping true to this belief, Duo Duo gave a brief yet highly evocative acceptance speech at the Neustadt Prize banquet. In an elliptical, at times almost hermetic language, Duo Duo shed light on his poetics through his own expulsion from contemporary Chinese history and within a universal "all-encompassing story."

Ladies and Gentlemen:

Tonight, in front of everyone here, I wish to keep my tone low, so that the word gratitude can be heard more clearly. This is a word that must be said, and should have been said a long time ago.

Upon hearing the verses of Baudelaire, Lorca, Tsvetaeva, and Ehrenburg for the first time, a generation of Chinese poets was already grateful—for the transmission of creativity from hand to hand during those stark years. Words, in the hands of their receivers, had directly become destiny.

Poetry hit us with its power of immediacy, and I believed that from that point of impact, the power would be transmitted back out from us.

Since then, my borders have been only two rows of trees.

Even as I speak, remnants of the 1970s still resound, and contain every echo of the reshaping of one’s character. One country, one voice—the poet expels himself from all that. Thus begins writing, thus begins exile. A position approaches me on its own. I am only one man; I establish myself on that. I am only a man.

I am not speaking about history, but about man, whose appearance in this word history has long been debated. In this word, life is led away by poetry, to search for, as Sylvia Plath said, “a country far away as health.”

I am speaking about writing, that difficult étude.

In the process, what must be spoken meets what cannot be said. Each word is a catalyst, requiring the writer to break out forcefully from another story, from the primitive camp where history, society, and politics converge, to touch upon that “what” and that “who.” At that touch, one finds the unlimited boundaries of man, concealed by words.

At this point, half of each word has been written, the half that can be understood. Grammar is still pondering the other half. Each word is not only a sign. Inside each word there is an orphan’s brain. No words can be younger, but inside the word suffering are all the secrets of being human.

Perhaps pondering words is also a form of seeking justice. If a monologue can invite a chorus, then perhaps it can speak for others as well. Poetry is self-sufficient in its uselessness, and therefore it is contemptuous of power.

At the very least, the ideal of poetry demands this: even as the poet is still catching up, it has already revealed its most dignified aspect. It allows light to be cast on the scales, which light must shine and move upon. Light therefore arrives where man himself can arrive, so as to recognize love anew.

What illuminates us is hesitancy, so action is always condemning; darkness becomes more complete, to the point that it has sealed up all its remaining cracks, without knowing that light in fact originates from within itself. And that is what words must penetrate through.

The present is thereby even more hidden, the hierarchy cannot speak this rule—a spell that has been written down.

When the road has already become an unstressed word, even when tracing its genealogy, what returns are only the echoes of this particular civilization. So we stop here, we stop at the place where we think we can go back and experience the whole journey, on a quest for that word which has been enclosed in ore along with a swooning, ancient past—a sealed-up riddle that is only testing its listener.

In a poet’s listening, at the limits of his honesty, at the ends of logic, a “what” will be opened, that “what”—the present moment. From its deepest roots, a word will burst out from the riddle. Perhaps this word is what has been revealed by hints: an approaching, an encountering, a dialogue.

The road is only in the present, and we use the echoes as milestones.

What I am speaking about is how a poet’s experience is brought into words.

After experiencing the cacophony of revolution, subversion, experimentation, and deconstruction, what can the poet still hear? Inside this word that has burst out from the riddle—silence—is our common condition: on the level of a completely material world, on a human physical level, we are allowing a dysfunctional intelligence to peck at and eat away the landscape; it is a continuation of slogans; a sustainable violence is using memory as fuel, and what has been replenished is the echo of our condition, because the exile of words begins here.

But from the discursive space created by the poetic canon, what constantly echoes is the speech that has never been separated from silence: there is only memory, no forgetting, because there are no mountains, only peaks. . .

The pantheon of classical Chinese poets is emerging, bringing mountain ranges, rivers, weight, and pressure along in their words and between their lines, to be with us not only where language breaks but also at geological fault lines, waiting for us to pick up where they left off—another season in this meadow of life. In another story, in the same allegory, the way we return to the sound of the fresco is the way the light creates our horizon.

At this point, we need the voice of an all-encompassing story to speak.

To speak of East–West, West–East, to speak of this common stage on which we all appear—the earth, the advancing starry skies and dwellings—our allies in writing, our readers—our grasslands under the sea . . .

Nature already has no other water or ink, the danger has been found, poetry has fallen to the periphery, and this periphery comes close to home. Poetry takes this periphery as a blessing and continues to offer rituals for the sick rivers, to offer readable landscapes for the heart.

This is the reason we persevere.

Norman, Oklahoma

October 22, 2010

English Translation from the Chinese

By Mai Mang

Mai Mang (Yibing Huang), who nominated Duo Duo for the Neustadt Prize, was born in Changde, Hunan, in 1967 and inherited Tujia ethnic minority blood from his mother. He established himself as a poet in the 1980s and received his BA, MA, and PhD in Chinese literature from Beijing University. Mai Mang moved to the United States in 1993 and earned a second PhD in comparative literature from UCLA. He is the author of two books of poetry, Stone Turtle: Poems 1987–2000 and Approaching Blindness, as well as Contemporary Chinese Literature: From the Cultural Revolution to the Future (2007). Mai Mang is currently Associate Professor of Chinese at Connecticut College. His essay “Duo Duo: Master of Wishful Thinking” appears in the March issue of WLT.

女士们,先生们:

今夜面对诸位,我仅愿望低调地言说,以便让感谢这个词能够听得更为真切。这是一个必须说出的词,且在很久以前就应当说出。

当初次听到波德莱尔,洛尔迦,茨维塔耶娃,爱伦堡诗行的音节,一代中国诗人已经在感谢——这严厉岁月里创造之手的传递。词语,已在接受者手中直接成为命运。

诗,以其瞬间就能击中的力量袭击我们,在击中处,我信此力也能从我们传递回去。

自此,我的国界只是两排树。

在我如此讲述之际,七十年代的残响还在回荡,里面有重塑人格的全部回声。从这一点——一个国家一个声音,诗人把自己开除出去。写作开始,流亡开始。立场,便自动向我移近,只不过是一个人,并以此确立自身,只不过是人。

我说的不是历史,是出现在历史这个词中被争论过的人。在这个词中,生命被诗歌带走,去寻找“一个像健康一样遥远的国度”。(西尔维亚·普拉斯语)

我说的是写作,那首艰难的练习曲。

其间,非说不可的遇到了说不出来的。每一个词是一个原因,要求写作者从另一个故事,从历史,社会,政治所汇集的原始营地强行突围,去触及那个什么,那个谁。在触及中,找到词所隐瞒的人的无限边界。

从这一点,每个词写出了一半,可理解的一半。语法,仍在对词叩问的另一半进行。每一个词都不是符号,每一个词内有一个孤儿的大脑。说不出更年轻的词,但在苦难这个词中有人的全部秘密。

也许,叩问词也就追问了正义。如独白能引来合声,也许就是代言。诗,以其无用而自足,并以此蔑视权力。

至少,诗歌理想是这样要求的:当诗人尚未跟上自己,已把最具尊严的部份暴露给它。是它,让光投在光必须照射并移动的刻度上。光,也就在人可抵达处抵达人,以便把爱重新辨认出来。

照亮我们的是踌躇,行动便总是在谴责,黑暗就更加充分,以致愈合了它所遗漏的缝隙,尚不知光也源其自身。而那是由词语洞穿的。

当下就更为隐蔽,等级说不出这统治——一个被写出来的咒语。

当道路,已成为一个读不出重音的词,即使在对其高谱系的追溯中,传来的也只是本次文明的回声。我们便一路停在那里,停在我们以为返回可以让我们经历全程的地点,追问那个与昏迷的远古一道封闭在矿石中的词,一个被封闭的谜,只考验它的倾听者。

在诗人的倾听中,在他诚实的极限,逻辑的尽头,会有什么被打开,那个什么——那个当下。从它更深更深的根据里,谜崩出词。词,也许就是由暗示所揭露出来的接近,相遇,对话。

道路只在当下,而我们把回声当里程。

我说的是诗人经验怎样被带入词语。

在经历了革命、颠覆、试验、拆解的喧嚣之后,诗人还能听到什么。这从谜崩出的词——沉默,里面有我们共同的处境:在一种完全形而下的水平上,在人的物理的水平上,任坏死的智力啄食风景,这是口号的继续,一种可持续的暴力把记忆当了燃料,回填回去的是我们处境的回声,因为词的流亡是从这里开始的。

但从诗学典范所创造的词语空间,持久鸣响的却是从未与沉默分开过的言说:只有记忆,没有遗忘,因为没有山峰,只有高峰……

中国古典诗人的群像浮现了,带着字里行间一路而来的山脉,河流,重量与压力,和我们在一起,不只在语文的中断处,也在地质的断层,等待我们接说——这生命草坪的又一季。在另一个故事里,同一个寓言里,我们怎样重归壁画的音响,光也就怎样创造我们的视野。

从这一点,就要由一个总体故事的说者说下去了。

说东方——西方,西方——东方,说这共同出场的舞台——大地,向前的星空与居所——我们书写的联盟,我们的读者——我们的海底草原……

大自然已没有另外的水墨,危险已被找到,诗歌已沦为边缘,而边缘靠近家园。诗歌享用这边缘,并继续为生病的河流提供仪式,为心灵提供可阅读的风景。

这是我们绵延的理由。