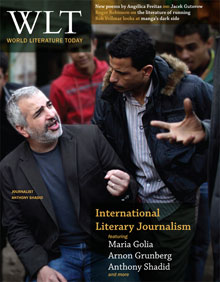

Reclaiming What Was Lost: A Conversation with Anthony Shadid

LEFT: Photo of Shadid by Nada Bakri. RIGHT: A photo of the ancestral home in Marjayoun by Anthony Shadid.

Currently the New York Times' Beirut bureau chief, Anthony Shadid has won two Pulitzer Prizes and many other accolades in the fifteen years he's covered the Middle East for the Washington Post, the Associated Press, and the Times. During that time, Shadid bore witness, at great personal risk, to many of the region's most historic moments. In 2002 he was shot in the shoulder while reporting in Ramallah, in the West Bank. Last spring he and three other Times journalists were kidnapped and held for four days while reporting in Libya.

A native of Oklahoma City, Shadid graduated from the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1990, where he studied Arabic and earned degrees in journalism and political science. While his first two books, Legacy of the Prophet and Night Draws Near, focused on Islamic politics and the struggles of ordinary people in one of the world's most politically volatile regions, his forthcoming memoir, House of Stone, matches years of tireless research into his own genealogy with a lyrical, first-person narrative. Shadid took a leave of absence from the Post in 2006–07 to rebuild his family's home in Marjayoun, Lebanon, the home from which his ancestors fled amid the chaotic implosion of the Ottoman Empire after World War I.

Shadid lives and works in Beirut, seeking refuge from work at his home in Marjayoun on the weekends.

Matt Carney: In House of Stone, you rebuild the house that your great-grandfather Isber built. In these very detailed, flashback-type passages, you show how it once was, which surely required some great feats of imagination on your part, only drawing from firsthand accounts of it and the rubble left. How does that sort of imagination differ from what you use in writing your run-of-the-mill news report?

Anthony Shadid: To be honest, it wasn't all that different, because I knew those passages would have to be as literary as possible. In some ways, I tried to make that writing perhaps more evocative than the present-day narrative. I wanted to be lyrical in those flashbacks. But in the end, I think the lyricism is still built on detail, which is built on reporting, in a way.

I didn't make up anything, and that was a real challenge. If I did try to imagine something, I'd make it clear that it was an imagination. So that was where all the research went in. I think the mechanics of writing are so brutal sometimes. I had to try to recapture details that were almost lost by doing countless interviews. It's funny, when my family reads this, they'll hear a snippet here, a snippet there, of the interviews I did with them that took so long. It felt very natural to me. The journalism part of that was to build those details so I could make the writing evocative enough that it was somehow memorable.

MC: The overarching conflict in House of Stone is between creation and destruction: the act of building a house in a place rife with conflict. You never quite spell it out as a good-versus-evil struggle—you hint at it, but you never take it quite that far. Why is that?

AS: Because I'm not sure it was good and evil, in the end. I think it was more a question of loss. "Can we reclaim something that is lost?" Honestly, I tried not to answer that in a straightforward way at the end of the book, because I think what we do is we imagine something that compensates for that loss. I don't know if we can reclaim loss or not.

It was actually an epiphany for me, the experience itself. You can imagine communities that, in some ways, don't overcome that loss, don't make up for that loss, but in some ways they make that loss irrelevant. I think that's really important. I think that idea of imagining identity and imagining community is not only a very personal narrative, but it's a very powerful idea for the Middle East as well. I think a lot of this war, this carnage, this evil that you mentioned is over these very restrictive identities, or smaller identities. Unimaginable identities, in some ways. I think there is an anecdote to that, perhaps, in imagination.

MC: You definitely get that from reading House of Stone, the notion that the American involvement in the Middle East has caused many long-standing consequences that you don't always get the chance to properly cover in practicing journalism.

AS: I've been covering the Middle East for fifteen years now, lived in the region—I was a student there in 1990-91—twenty years almost. You could almost write the history of the Middle East, the history of Marjayoun, the history of Lebanon—you take your pick of the region right now—and it's a history of borders, both physical and mental. Within the consequences of history, that is what is so powerful to me. Marjayoun died because of borders being drawn. It's agonizing dealing with their own history. . . . You're not going to be able to fight those borders. Those borders are borders, they remain, we can't imagine anything that can transcend them. It became a real tension I felt in writing the book, in trying to explore and understand that gulf.

MC: A theme that pervades the book is hope. You yourself have been kidnapped, seen morgues with tens of thousands of unidentified dead, you spent a good deal of time with Assaad, a character whose outlook is so negative, and even end the book with the passing of your wise, caring friend, Dr. Khairalla. Where does this hope come from?

AS: Assaad depressed me. When I was spending the most time with him during that time in Marjayoun, I really did dislike the town, and I didn't want to be there. I know it sounds almost disingenuous for me to suggest that this worked out as well as it did, but I think I really did make peace in the end with the town, because I created a community in Marjayoun that meant something to me. It was that humanity. And I didn't write this in the book, but it was Dr. Khairalla's humanity. There was a spiritual element, to both our friendship and to his existence itself, that resounded. And that humanity I see in him, which I've seen time and again in the Arab world, the Middle East, and Lebanon, I've never lost contact with that.

When I was arrested in Libya in March 2011—abducted, actually—it was tough. There was a lot of beating early on. And you know, bruises heal, you get over it, but that kind of fear and terror lingers for a while. We had gone through our worst beatings after we were taken halfway across the country in the back of a pickup truck. When they took us to an airport I panicked, because my wrists were bound so tightly that I felt like I was going to lose my hands and this one guy came up to me—I thought he was about to hit me, so I turned my head—and he whispers "I'm sorry" to me in English. And even as brutalized, as traumatized an environment that I found in Libya, there was still that humanity of the culture. Despite all the wars, all the carnage, all the shit, to be honest, that I saw in 2006, before I started to write House of Stone, that culture has never lost its humanity. That's something which keeps me humane, it keeps my work humane, it keeps me hopeful about where we're headed. It makes me think that we're going to end up okay. I'm not sure what it's going to look like, but I figure it's going to end up okay.

Ritual tethers us to a place and a time. Especially with coffee. In Marjayoun, you'd have coffee five or six times a day. It's the cadence to life, it's the foundation of social interaction, it's the way friendships are renewed and deepened.

MC: On page 69 of House of Stone, you find your way to the limits of journalism. When it stops, what begins? History?

AS: What I've always been frustrated with, in journalism itself, is that the ambition of a story never meets the story in the end. How can I rephrase that better? "You never feel that the story fulfilled the ambition you had for it" is a better way to phrase it.

That's just endlessly frustrating to me. Of course I spend hours and hours on outlines. I outline every story that I write. And then, because of space constraints, because of perspective, because there is a sort of straitjacket on journalistic writing, on reportage—especially that reportage which finds its way into a newspaper—you try to break those rules, you try to rub against those rules, but in the end you still have to play by certain rules. I'm not talking about bias or anything like that, just the very mechanics of writing.

But I think when you take a step back and actually look at the difference between journalism and writing, or the limits I talked about in that passage of the book, I think it's a very sensitive line when it comes to journalism. Reporting on the Arab Spring, for instance—the revolutions—was the most tumultuous year I've ever worked as a journalist, and there are probably five or six stories that'll hold up over time, even though I wrote over three hundred. It's kind of frustrating when you look back—maybe there's more than that, maybe ten or fifteen—but still, it's just a fraction of what you've done.

I think that's what I'm talking about in House of Stone a little bit. We don't get to see the consequences of those stories. We don't get to read about the characters' change over time. That would necessitate more comprehensive writing, in some respects, and I think that is frustrating.

MC: In reading House of Stone, I wondered about bayt [Arabic for "house," with connotations of family and home]. Do you think it's something you can create outside of the Middle East?

AS: I do. Bayt is a state of mind. We were talking about imagination earlier—I think bayt is the cornerstone of imagination. It can be something as physical as the house in Marjayoun became. But I think it incorporates that sense of community which is infused with memory and hope and ideals. I have to say, in the end, bayt was the house in Marjayoun to me. Especially for someone who hasn't had much of a home for a long time because I've been wandering for so long. But I think it's also this idea of what the house in Marjayoun represents: a Middle East that feels very dear to me.

It kills my wife—when I go back to the house I just sit there, she thinks I'm obsessed with the details of the house and I'm really not. It's what the house is evoking and what it represents and what it means to me. It's a receptacle, in a way, for imagination, for hope, and—let's be honest—for fear, too.

MC: Your ancestors fled Lebanon for North America and became very happy here, establishing their bayt in Oklahoma, Kansas, and South America.

AS: That's exactly right; they created home. I think they imagined their own communities. My grandparents have that house in northwest Oklahoma City—they created their own Marjayoun in a different place, their notion of Marjayoun. They always called their ancestral home Jedeidet Marjayoun, or Marjayoun, and they felt very powerfully that they had imagined their jedeidet as far away as you could imagine it.

MC: You and your foreman, Abu Jean, developed a very intimate friendship despite your enormous contrasts. You're American and exist within deadlines, he's Arabic and representative of an older world. I recall that turning point where you realized his word for "tomorrow" meant something more like "eventually." How did that understanding enrich your bayt?

AS: It's funny, I became less stressful! It was such an epiphany, I'll never forget that day. "Anthony, tomorrow"—he'd use the Arabic word, bukra—"tomorrow, the cucumbers are going to come up," or something like that. After I thought about it, I went to my friend Hikmat and told him, "I get 'tomorrow' now!" It more literally translates as "tomorrow, and after," so it's even looser than the idea of "tomorrow." All I'd dealt with for so long were deadlines, and I was finally able to embrace that moment where not only did deadlines not matter, but time didn't matter all that much in the bigger scheme of things. That was something wonderful about Abu Jean, in building the house. To him, it wasn't about finishing the house, but the experience itself, and being a part of that experience and living that experience and the community he had in the warshe (workshop), and that was something I learned a lot from because as journalists, as reporters, it's always headline, deadline, you know? "File that story." "Why are you two hours late?" I think when I look back at that moment, I realized we have time. We can linger for a while.

MC: You write about the character Assaad, who lived in America for so long and always imagined life to be better in Lebanon. Then when he gets there, he becomes even more depressed. "The curse of a generation," you write. "Always looking for something so much more, so much better. The cost of too much freedom." What do you mean by that?

AS: Assaad had the freedom that his father wouldn't have had, that his grandfather wouldn't have had. In the end, I think he never found anything. To me, Assaad is the most tragic character in the whole book because he had no home in the end. He was neither Arab nor American, neither there nor here. He was so sad in the end when he was getting ready to go back. . . . You got a sense that he was setting himself up for even more disappointment. That's what I meant about his generation, that they encountered a lot of disappointment in a lot of ways.

MC: You had that opportunity which Isber was hoping his descendants would have when he sent his children across the Atlantic Ocean and you came back. America afforded you great opportunity. There's a nice cyclical quality to that.

AS: I found Isber a very fascinating character because I didn't know that much about him, to be honest. I knew about the house and I knew about who he was, what he represented, and what he did, but I didn't know that much personally about him. So when I researched him—and I tried to bring this out in the book, although I didn't want to be too heavy-handed with it—there are a lot of intersections between his narrative and mine. These ideas of house and family and loss and building something lasting and the cost of ambition. It was interesting to me how much I felt, as the book went on, as the writing went on, how much echo there was between our lives. There's permanence to my decisions because of his.

MC: One of the last parts of the book covers the baptism of your friend's daughter. You also talk a lot about customary preparations of food, especially coffee. There's a thick atmosphere of Old World ritual. What's the role of ritual in a world of instant communication?

AS: When I was writing about the baptism, my fear was that ritual is all we have left sometimes, in the end. Ritual devoid of community, devoid of life, devoid of meaning in some ways. We're left with hollow ritual, which marks the extinction of an older community.

Ritual tethers us to a place and a time. Especially with coffee. In Marjayoun, you'd have coffee five or six times a day. It's the cadence to life, it's the foundation of social interaction, it's the way friendships are renewed and deepened. That ritual becomes, I think, the depth of a community in a way that instant communication never could.

I've always been struck by this. Focusing on ritual came out of a story I did in 2003 in Baghdad. It was on the death of a young boy during the invasion. Again, the point of humanity—both for the region and for readers to understand that humanity—meant something to me. I wanted to cover from the moment that boy died in Baghdad to the moment he was buried. Basically a day in the death of this young boy. I remember watching as they were washing his body, just how practiced those rituals were. How many times those motions had been done. Time after time, year after year, century after century. There's something so powerful about that. I'm not sure if the power comes from death or from elsewhere, but it haunted me and it still haunts me, that ritual can tap into such a broader idea.

MC: Is your biggest personal conflict celebrating creation amid reporting destruction? Because that's sort of the premise of the book, that you're building this home, something of a monument to creation, in a place so full of conflict.

AS: What I saw the house as, and I say this to my wife when she asks why the house is so meaningful to me: It's the only thing I've created in this world. And because there's so much death, so much destruction, so much carnage, I have to ask: Is there a way to stop loss? Is there a way to reclaim what was lost? I still don't know the answer. We have to think of it in a different way, and I think that's where imagination comes in. It's the question that haunted me going into this experience, and still sticks with me. How do we stand loss?

Maybe it doesn't really matter? I don't know. If we can imagine identities that are transcendent, or imagine communities that are transcendent, I wonder if loss even matters. I'm not sure if that's the case or not, but that's kind of how I came to it in the end. I think this matters not just for Marjayoun, or my life, or this house. I think that matters to the Arab world. The Arab world cannot imagine identities in a different way. The wars that I've covered for fifteen years have gone on for generations.

You go to places like northern Iraq or you go to the border between Turkey and Syria, and you do see new identities and communities emerging there. That's actually what I want to do my next book on. I found that very hopeful and very meaningful and very powerful. It's kind of a counternarrative to this idea of smaller and smaller identities that have defined the region for so long.

MC: What is it that you find encouraging in these new identities?

AS: I'm not going to try to be an academic or historian, but if you look at the Arab world over the centuries, cities themselves have been much better at negotiating conflict, negotiating community, and forging a broader sense of identity that can embrace diversity. I see that hyperlocal identity becoming more prominent and more powerful in a lot of different places. I see it in northern Iraq, I see it on the Turkish-Syrian border, I see it in some ways in Lebanon. In these places you don't have to become Sunni or Shia or Christian or Muslim or Lebanese or Syrian or Turkish. These smaller identities go on and on until it's mind-numbing. Your other identities are embraced within this larger notion of the urban sense of self. I see that returning and I think that's very hopeful, even for a place like Marjayoun. There's the possibility that you can be Marjayouni instead of Lebanese or Greek Orthodox. I think it's a century-long process, but when it comes to identity, it's a source of hope that I see.

MC: House of Stone ends with several characters talking about Marjayoun dying. You agree. Hearing you now talk about how there's hope, and how you love to go to your home back there, has me wondering if that's changed at all.

AS: The town is going to die. Marjayoun won't make it. But I feel very powerfully about the community experience. I created my own sense of community there, my jedeidet in a way. The same way that Dr. Khairalla did, or Kareem. The jedeidet that was able to bring us together then and in the time since has been very meaningful to me. It really is the place I feel most at home.

December 2011