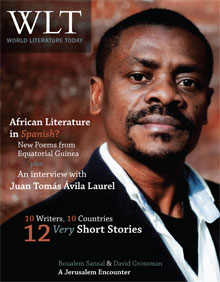

The Uncertain Territory of Memory

A Conversation with Chilean Writer Roberto Brodsky

Roberto Brodsky (b. 1957) came of age in Santiago de Chile during the revolutionary years of Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity government (1970–73). Born to Ukrainian Jewish immigrants that escaped the pogroms during the first decades of the century, Brodsky grew up immersed in leftist politics and culture. During the Popular Unity he was a young militant in the FER (Frente de Estudiantes Revolucionarios). In 1973 the right-wing military coup divided his family, forcing them into exile in Venezuela, Argentina, and Spain. After his return to Chile in the early 1980s, he worked as a journalist and playwright and became involved in clandestine oppositional press networks.

Roberto Brodsky (b. 1957) came of age in Santiago de Chile during the revolutionary years of Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity government (1970–73). Born to Ukrainian Jewish immigrants that escaped the pogroms during the first decades of the century, Brodsky grew up immersed in leftist politics and culture. During the Popular Unity he was a young militant in the FER (Frente de Estudiantes Revolucionarios). In 1973 the right-wing military coup divided his family, forcing them into exile in Venezuela, Argentina, and Spain. After his return to Chile in the early 1980s, he worked as a journalist and playwright and became involved in clandestine oppositional press networks.

Latin American societies somehow became ruthless, and fell apart, then had to be rebuilt. Now, in the aftermath, there is the search for that site, the memory of that disaster. It is in that search, I think, where the most telling revelations are to be found because they are revelations that relate to the future.

In more recent decades, he has emerged as a prominent novelist and screenwriter whose work deals largely with memories of Chile’s dictatorial past. His novels, including El peor de los héroes (1999; The worst of the heroes), Últimos días de la historia, (2001; The last days of history), El arte de callar (2004; The art of being silent), and Bosque quemado (2007; Burnt forest), explore themes such as social activism, education, human rights, exile, return, trauma, and memory. Along with Andrés Wood, he co-wrote the screenplay to the enormously successful feature film Machuca (2004), which offers a nuanced portrait of the events leading up to the 1973 military coup through the eyes of adolescents. His most recent novel, Bosque quemado, which has recently been awarded the prestigious Premio Jaén de Novela in Spain (2007), tells the story of Moisés, a communist cardiologist who struggles to work through painful memories of political exile in the wake of the military regime.

Currently, Brodsky is working on a new novel and documentary script focused on Chilean cultural production of the 1980s under the Pinochet regime. This conversation is largely centered on Brodsky’s vision of memory, history, and representation in contemporary Latin America as well as on his friendship with writer Roberto Bolaño and his novel Últimos días de la historia that is soon to be translated into English. The interview took place on February 24, 2011, in Eugene, Oregon, where Brodsky spoke to students at the University of Oregon and later presented the documentary film Mi vida con Carlos (2010; My life with Carlos) at the Cine-Lit International Conference on Hispanic Film and Fiction in Portland. Brodsky co-wrote the script to the documentary with Germán Berger-Hertz. Currently, Roberto Brodsky lives in Washington, D.C., and teaches as a visiting scholar at Georgetown University.

Memory: Making the Present Less Deceitful

Lisa DiGiovanni: In the last decade, we have seen an outpouring of headlines, films, and novels that explore stories of Chile’s dictatorial past. At the same time, there has been an extraordinary interest in nostalgically remembering the Allende years. What do you think of this “memory boom”? Do you view it as an exploitation of the topic? Is there an excess of memory?

Roberto Brodsky: Well, I think that after a traumatic period, societies often initially want to cleanse themselves of the past. But later the reconstruction and representation of the period begins. It seems to me that within that context the production, or overproduction, of memory texts and cultural products is normal and expected. What I find interesting is the variation in cultural production. On one hand, there is a type of production that memorializes the struggles that took place and recollects how we were. On the other hand, there is a kind of production that aims to represent a sense of how a community was, the efforts that were put forth, and the outcomes in the present. I consider the second type far more compelling because it deals with the search for what we might call “the Latin American catastrophe,” which involves the processes that occurred in the 1970s and ’80s when tremendous political developments were taking place, huge collapses and black holes. Latin American societies somehow became ruthless, and fell apart, then had to be rebuilt. Now, in the aftermath, there is the search for that site, the memory of that disaster. It is in that search, I think, where the most telling revelations are to be found because they are revelations that relate to the future. They are forward-thinking. It’s not merely a task of memorialization or archival categorization but rather a task that involves a political intention or an attempt to guard or protect against the potential threats that the future may present. So there are two types of cultural production: usually there is one that is more traditional and memorialistic, which tends toward preserving the motifs of a period, and another that moves toward unexpected discoveries and probes what happened in terms of what might take place tomorrow as well.

LDG: So we can say that there are certain uses of memory in the present?

RB: Yes, but what fascinates me most is when memory is represented as a construct of the present. That is, when we can see the shifts in time, the ellipses that occur in representations, the attacks of involuntary recollections, the moments that might interrupt one’s speech with undetermined, unsettled, or ineffable images which suddenly appear, making the present less deceitful. I think that is the point; memory is something that reveals rather than conceals, making the present less deceitful. The more traditional type of cultural production conceals; it shields us, allowing us to anchor ourselves in a present without actually seeing it, and therefore without discovering what is in that present that sheds light on what happened yesterday.

Pedro García-Caro: Your point connects very well to one of the concepts we wanted to address, which is monumentalizing the past and creating public memory spaces, which to some extent has occupied much of Chilean cultural production. To what extent is this effort the result of a fixation with the past and with the trauma that does not open the way for the expression of the future projects to which you have referred? Can one monumentalize the past without pause and without reflection?

RB: The problem with monumentalization is that something is put in place to later forget it. The best way to forget something, and that which constitutes its discursive power, its sign, is to monumentalize it. It is to erect a building, a statue, a memorial, a symbol that allows us to refer to that monumental tragedy, epic, resistance, or whatever, and, by extension, to pass it into oblivion and to create a new territory. But on the other hand, I think that it is important to create a space for memory and the different representations of the past because they need a space. What type of place is that? That is the question. What place? Is it in the monuments? Is it in the institutions? In civil society? In grassroots groups? Or in art itself? I think that is the question, and I do not really know what place that is. I know that my place, or a possible place, is in fiction—in the sense that it is in fiction that we might represent the presence of memory, working “active” memory, as we discussed—a type of memory that is constantly rearticulated from one day to the next. For me, fiction is the space where it is possible to articulate discourses of memory and of the present that enable us to look at the events of the past in a less deceitful way. In fiction we might voice memories of past epic myths of the resistance, as well as the need to anchor them down in the present. Each of us finds our way, and I understand that from the social point of view there might be a need for a type of monument to which you are referring. Yet I think that monumenalization serves to anchor down the past in order to forget it.

Beginning to Narrate: Scraping the Pot

PGC: What is most worrisome is that entire generations have been dedicated to this type of memorializing project that whitewashes memory and does not allow them to be vigilant of the arrival of neoliberalism and the dictatorship of the market.

It is as if reality had disappeared and you were in a dark room, and in order to begin communicating you had to hit yourself and realize, “Ah, this is a leg, this is an ear, a piece of hair,” and little by little you began to open your eyes after having become accustomed to the darkness.

RB: I think that removing oneself from the present is terrible. We have to be very careful not to evade the present. If one is absent from the present, sheltering themselves, or retreating to the preservation of memory in an almost archaeological sense, I think that they are failing to see the whole realm to which those memorialized facts belong. One cannot escape from the present or withdraw because those events belong to a present that is always being constructed. One shouldn’t become outdated with respect to what is taking place in the present. Memory essentially consists of things in the present that are linked to the past, things that suddenly appear and break into the present unexpectedly. So, I think that the archaeological approach to reconstructing the past is very problematic. I understand that there are people who do it, but it is dangerous insofar as it threatens one’s ability to capture and critically represent important signs that are unfolding in the present.

LDG: Speaking of that critical standpoint, in your work there is a powerful historical confrontation. The characters in your novels and scripts embark on a self-critical path, a path of self-reflection. In that way you underscore a certain collective responsibility and reject the mythical narrative of activism.

RB: Well, for me the loss of that shared cultural atmosphere that characterized the 1970s and ’80s in Latin America was extremely profound. When I say “that shared atmosphere,” I mean the common ground that when one person said “x,” the other understood “x.” At some point that was broken, and, as a result of that break, it became impossible to make sense of reality in Latin America, or the reality of that environment, or to represent it without putting yourself in the heart of the problem. All my fictions are narrated from the first-person point of view. Some may be fictitious or testimonial, but the story is always formed from the first person, because that perspective indicates an example of the real. Therein lies the assertion, “That exists, that is me, and I have to see how that affected me, and how I confront what happened.” I think that there is a need to verify the existence of certain things, to render visible the existence of certain things. My intention isn’t necessarily conscious, but that self-reflective element is a fundamental part of my narrative representations because I think it is from that standpoint that you can truly reconstruct reality. It is as if reality had disappeared and you were in a dark room, and in order to begin communicating you had to hit yourself and realize, “Ah, this is a leg, this is an ear, a piece of hair,” and little by little you begin to open your eyes after having become accustomed to the darkness. Gradually, you begin to regain sight and recognize certain things. For me, that has been the way to recover the symbolic, the valuable, and to start thinking.

In my fiction, I try to put the narrator, or narrative, in an absolute critical confrontation and destabilization. I ask, “Let’s see if he rises up. If he survived, let’s see if he rises up. You were saved. Why were you saved?” The point of these narratives is not so much that they are survivor stories, but rather narratives that express, without seeking justification, that “I was saved and I’m here for the present. Because I am a survivor.” So even if you don’t narrate from the survivor’s point of view, that is, if you narrate from the standpoint of knowledge of certain things rather than fragility or weakness, the narrator must still recognize his or her own position as a survivor. It’s as if there was a remnant in the destruction of the symbolic and the representational. It is that remnant that one must implore to start telling the story anew.

I search for that occasion to begin writing. Take, for example, Gonzalo’s character in Machuca. He says, “I’m not from here, I’m safe.” What is interesting is that there is no salvation. Salvation is for others. He knows that his salvation lies elsewhere. His salvation lies in recovering the story in the aftermath. I think that at some point in Latin America we came upon the remains in the aftermath. We began scraping the pot, and from that point on we started telling the story again. We had reached a point in which our old mythologies seemed bankrupt; the stories, performances, and promises that we had once told of the future utopias of the continent were empty. Those narratives no longer filled people with enthusiasm; they crumbled, and a dystopian vision took hold. The disenchantment was immense, and we had to begin scraping the pot to see what was left. What remained? What shred of truth might remain in that great accumulation of events, which seemed to bespeak the apocalyptic Aguirre, the Wrath of God, coming to tell us that this is the dream? What remains of all that? We reached that point. There are a fair number of writers and artists who have reached that point and have begun to salvage what remains. From there, they begin to tell the story.

LDG: Rescuing things but with a very critical eye—

RB: Exactly. There is a certain foresight that one learns with respect to the world. It is not that defeat is completely insurmountable, as (Alberto) Méndez expresses when chronicling defeat, or that hope cannot be recognized in anything. It is more a question of comprehending the dimensions of the defeat. And when you know the scale of defeat, you are very careful about the promises and representations of myths, of discourses, and of the legendary tales that you construct about yourself and your environment and your past. One becomes very heedful.

El desencanto

PGC: That image of the pot, of scraping the empty pot, connects to the idea of postmodern cynicism and the feeling of disenchantment with utopias. But what you are suggesting is a distinct version of the postmodern that differs from that of the pastiche, the quotation, the parody, the metatext, and other worn-out postmodern forms. You talk about something much more realistic, without grandiose projects, nor modernist, nor Stalinist, but rather of an attempt to rebuild, little by little, a new project of coexistence. How do you stand in relation to what we might consider a generational disenchantment?

When someone reads a work of fiction, what are they looking for? Somehow, one seeks an insight, an experience, and a story of a world, or a glimpse into another world that is more or less recognizable,which does not have to capture everything but might offer us something. We either push it aside or devour it. So, it cannot be meaningless.

RB: Yes, absolutely. Well said. Postmodern pastiche and the ability to get excited about lies and to mix them with truths, and philosophies with stories, and testimonies with whatever. For me, that is something that others do, but it doesn’t really work if your project is not to tell lies, but rather to observe and to try to live “the real.” To not get excited with the lies. Nor to make yourself a prophet of the truth, because therein also exists a trap. Quoting Juan José Saer’s thoughts, it’s about securing yourself in that space between the enthusiasm of lies and the prophecy of truth, and walking a very thin line between those two great enthusiasms that want to devour you. They can capture you and seize your entire ability to discern. That is the most difficult challenge, which in fact is best learned with defeat: the ability to perceive. It is about reconstructing, perceptively and critically, that world of yesteryear as well as the world of the here and now to inhabit and maintain.

I don’t want to criticize anyone or speak negatively about certain works, but there are some novels that you come across that not only reproduce an outdated or worn-out style, but also place their bets on a useless reality, one that I do not find helpful at all. That type of fiction serves as decoration. It serves the state. So some of us feel compelled to distance ourselves from the postmodern model as well as the realist account, the realism that seeks to render the truth. In my case, I feel that I have to be on uncertain ground in order to write. Perhaps it’s something that I have learned from hard times. I have to remain somewhat dubious or disoriented to be able to see clearly. Perhaps that is how I have come to perceive and represent things in a more honest way. I feel that writing fiction intuitively is ever more challenging and rare. So, one must be proactive to keep it alive, to not allow it to burn out. For those reasons I feel distant from those projects that are comfortably situated in postmodern discourses that combine the Popol Vuh with an exhibition at the MOMA, with an Egyptian who is burning in a plaza . . . where the symbols are interchangeable and you have no value to put on them. I don’t agree. I think that we have to prioritize certain things and that fiction must have a certain order. In film one must place the camera in a certain spot, here or there. Fiction begins with one thing or another. It is not all the same. What you incorporate first or second actually matters. Things have a certain sequence. Although we might live completely inundated by the current ethos of simultaneity and instantaneity, I think that when one represents something he or she needs to recognize one thing first, then the next, in order to generate a certain conflict, to present what is actually transpiring. . . .

PGC: What you are proposing, then, is to create a conflict and not necessarily another “Grand Narrative”?

RB: Exactly, because we don’t need grand narratives. Clearly what we need to do is observe, be it macro- or micronarratives. Above all, we need to see. When someone reads a work of fiction, what are they looking for? Somehow, one seeks an insight, an experience, and a story of a world, or a glimpse into another world that is more or less recognizable, which does not have to capture everything but might offer us something. We either push it aside or devour it. So, it cannot be meaningless. It has to be meaningful. I understand that there might be a younger generation that is more liberated from the restraints of mimesis or from the attachment to order or logic. Yet in my case, I do not feel bound or enslaved by such ties. On the contrary, these frameworks are necessary for me to be able to freely exercise the ability to perceive, to move about in that space.

LDG: You spoke of the difficulties of representation. I would like to ask you about the notion of “performance.” In your novel Últimos días de la historia (2001; The last days of history), you explore the relationship between “performance,” the dictatorship and postdictatorship. What has drawn you to the notion of performance in these contexts? Can you elaborate on your concept of performance when you wrote the novel?

RB: Yes, the concept is very concrete and concise: the body is something that cannot lie. In a context characterized by lies and deception, like a nightclub in Santiago where eccentric types are all around and everything is artificial, one inhabits a body that cannot lie, which strips down, revealing itself and telling the story. That is the context of the Chilean Transition—a context of lies overlaid with more lies in order to engender a general fiction so that everyone might coexist. That is a transition to democracy, and the trope of the performing naked body inserts itself into that context to present an undeniable truth. Of course, that naked truth has no space because it is presented in a completely artificial environment. The audience is artificial, and the performer also employs artifice to convey his message.

LDG: And of course no one understands his message in the novel. He ends up feeling very frustrated.

RB: [Laughter] He is a type of clown of the Transition, a crazy historian who strips at a nightclub telling his story about the years of the Popular Unity. What people go to see is a naked guy, to get drunk and to have a good time. He, on the other hand, is obsessed with truth. That is what the story is about—the encounter between a radicalized and passionate individual and an indifferent environment, a public that is ready to consume him one moment and forget about him the next—to accept him in that miserable and precarious exchange and then to forget him. But suddenly that individual sees his old friend within that public and something happens. His friend recognizes the truth in the performance. What does that mean? That there is a testimony within the performance and that there is a witness of the witness. And so a completely impossible situation is produced: both have to face the past. What was true? What was false? How did they experience their adolescence? What passions did they really have? Were they really inspired by the revolutionary cause or were they inspired by sexual desires? What really happened back then? In the novel, there is a persistent reflection upon that period and upon the characters’ formative years, upon that era when they came of age. For me, that is the framework of memory which operates in the novel. Logical coherence and continuity break down, and responses often contradict intentions. The machine functions to reproduce something similar to memory. Of course, it is totally fictitious and can be seen as a parody of a narrative device that seeks to convey a transparent recuperation of memory, one that proposes to situate the world upon solid ground, without gaps or folds. The machine has that function.

LDG: But the machine also has a very interesting sexual function. Can you elaborate a bit more on that connection?

RB: Yes, it has a sexual function because it permits the main character to have a prosthetic. It is as if the main character had been emasculated, cut off, as if he had the desire in his head but he did not have the body parts, or as if they were amputated, leaving him unable to realize his desires. As such the machine is a type of artificial body part, allowing him to carry them out. It also gives him crazy images; balloons and strange liquids shoot out of it. It is all very pornographic, and I think that there is some connection between obscenity and memory.

PGC: It is also a posthumous moment, a moment in which you create a type of Chilean postmemory cyborg. Related to that idea, of the fragmented and castrated body that exhibits itself in public to create a certain revelation or an anagnorisis, we wanted to ask you about the relationship between your main character in the novel Últimos días and the real “happenings,” art installations and street performances by the avant-garde group of artists “Colectivo de Acciones de Arte” (CADA). Their art actions created a direct artistic challenge to the censorship and to the triumphal discourses of the Pinochet regime, challenging the televised propaganda and other types of mass media. How would you describe your relationship or your perception of the artistic works of Eltit, Zurita, Balcells, and others? In what way is your narrative an archive of that era? Perhaps it is comparable to Bolaño’s portrait of that era in Estrella distante?

RB: That is a very interesting and thorough question. My stance toward CADA, and with the performance of that time, was almost that of an observer, a tourist I would say. They were a bit older than I was, and I looked at their artistic interventions in and about public space as a type of endpoint of representation. There was nothing to represent, you could not do anything except interpose yourself; you could only scratch the pavement, throw paint on something, cross-dress as women, and go out into the street like “Las yeguas del apocalipsis”; Zurita threw acid on himself. It was a very direct way of using art to deal with a completely oppressive and closed state with no capacity for dialogue. It was a way to break the monolithic structure of the state, so it was therefore a political intervention. I watched with great interest, and at that time I had a theater group of my own that was of another character—that was not as avant-garde or postvanguard, but rather mischievous in character, using black humor, and alluding to the general insecurities of the time to generate a certain complicity with the audience.

CADA did not want a public. Their art actions did without an audience in the typical sense; their public was absent, they had disappeared. In my experience during that period, the audience did exist and there was a need to get close to them, to reconstruct discourse, to rebuild solidarity through a certain complicity, humor, and shared recognition that we were alive, that we would persevere together, that the tunnel ahead was still long but we were moving through it together. Our discourse emphasized closing ranks. Therefore, I saw CADA from a different perspective; or rather, I viewed representation from a contrasting standpoint. On the other hand, CADA later went through a reflective stage in which they began to reconsider and debate their own art actions. I think that Últimos días shows a connection to that group, to the obscenity. The historian, who locks himself up in his cave with his rupestral art, then closes himself into the nightclub for his performance—a performance that has an obscene element. There is something totally obscene in his intention: to show himself, to show everything, absolutely everything.

No. What I had, I threw on the table. I laid out what came to me in the moment, and that ended up being the novel. It is a work that emerged like a card game that was not planned nor thought out in my head. It was almost like an explosion.

I think that something similar actually took place. Beyond the dictatorship, which was the real audience for CADA, the Concertación government continued to be obscene. The art actions of CADA were shown, but without the context of the dictatorship, which was their direct source of reference. In a way, not intentionally but intuitively, I see the whole memorialistic desire to recuperate what happened during the dictatorship as something obscene from the point of view of a historian. History is the angel that looks back from the other side of the destruction, the Benjaminian Angel, which is the central figure in the novel. So, his entire project is hidden away in the nightclub, and there he devises a purpose for the machine, which is an artificial appendage of his own desires. He is surrounded by an obscene environment, in which he is unable to captivate his audience because, in reality, they are totally absent. His only real public is his old friend that suddenly appears, with whom he later drinks a few beers and remembers what could have happened, or not.

I think that the novel is driven by those key points. Upon writing it, I threw a lot of cards on the table without realizing it, without having consciously chosen blue, green, red, or black. No. What I had, I threw on the table. I laid out what came to me in the moment, and that ended up being the novel. It is a work that emerged like a card game that was not planned nor thought out in my head. It was almost like an explosion. For that reason, different elements in the novel seem somewhat precarious, open-ended, and leave much up to the reader. It was, of course, a shot in the dark that I did not want to organize coherently. I only structured my thoughts enough for the novel to be legible, but I did not try to give it a logical organization nor to create a coherent story that would permit the narrator a happy ending, or to recuperate history, or to make memory be the ultimate hero. No, not at all.

LDG: In that way your project goes against the coherent narrative of the dictatorship in both content and form. There is a certain challenge to that logic, to that coherence.

RB: It is like an utterly incoherent coherence. It is a type of incoherence that offers its own form of resistance, survival, and life. I don’t know, but the novel builds on that line of thought.

PGC: They are narrative fragments facing the possible control of a narrator that would end up being a dictator . . .

RB: Exactly, a ruler of the land, one who controls the territory. In Últimos días, someone in the audience insults the narrator, the public screams at him, as in the case of most porno shows. The audience participates in the way they want. I think that in that space there also lies the obscenity of the Transition. Pronounced in that period, “the nation” became an obscene, repetitive word because at that time we had to provide some cohesion to the narrative of the Transition after such a terrible dictatorship. And so we heard the word “nation” all the time. I think the figure of the historian in the novel, who tucks himself away in the bar to do his pornographic show with the help of a machine that projects images of 1973 and which is an extension of himself and of his own desire, is the most disruptive model that challenges the logical narrative form.

PGC: Can we classify the text as a type of postnational satire?

RB: Yes, in fact, I think that it is a postnational satire or parody, but without an audience. That is what has happened in Chile with the Transition. The Transition made the public disappear. It is interesting, during the dictatorship, for the artists of CADA and for all of us, we were up against the dictatorship and our artistic efforts were directed against the regime. Later, when the dictatorship was overturned, a new public emerged within the context of the Transition. At that time, the connections that had previously formed were severed and the solidarity that had developed was abandoned. From the most avant-garde movement to the more traditional, we all were left without an audience. Curiously, in that period, the “New Chilean Novel,” which itself is a fiction, was created in an attempt to garner a new public and an apparently organic and logical narrative form.

LDG: So you wouldn’t say that there is a direct parody of CADA within the novel? In Bolaño’s narrative the parody is quite clear.

RB: No, not intentionally. To be honest, I would often laugh at the “Art Actions,” or better yet, I thought that there was a lot more ideology within them than what it seemed. That was my problem. I realized the importance of the political act of the interventions, but they were so weighed down by ideology that it turned me off and made me doubtful. It seemed as if they were escaping one trap for another. I think that the story in Últimos días aims involuntarily at the theme, at the dead ends of ideologies that form part of the resistance to an oppressive context.

PGC: Perhaps we are facing a dialogue with the dictatorship rather than a particular ideology, as you describe it, entering into a dialogue and even on its own terms.

RB: Precisely. What could CADA really attempt to do under those circumstances? First of all, they [CADA] wanted to make the newspaper headlines. But, of course, they [the regime] were not going to recognize their actions. The context in which it all took place really undermined any recognition. The hand that you were dealt was already against you. Everything was hyper-censored and controlled. I don’t know if CADA sought out recognition within the context of the dictatorship, but I know, because I saw it and I could decipher their art actions, that there was a strong ideological component, a component that was necessary in the moment, but that I saw as defunct beyond that point. It seemed to me that their ideological aims beyond the dictatorship were obscene. I have my doubts; I know what my differences were. I think that they got too wrapped up in themselves, and therefore closed off to the more relevant possibilities that could have existed.

LDG: Perhaps that could lead us to our next question about Roberto Bolaño. We would like to ask you about your friendship with him. I know that you have great respect for his work. Could you speak to us a bit about him as a person and his work? Perhaps later we could discuss the theme of exile and the various perspectives of it.

RB: I met Bolaño in 1999, when he was invited to Chile by the magazine Paula to be a member of the advisory board, at which time he offered an account of his return to his country of origin. At that crossroads, I met him because I knew people at the magazine. Our meeting happened to coincide with the publication of my novel El peor de los héroes (1999; The worst of the heroes), and I gave him a copy. Based on his subsequent reading of that novel, we formed a connection and he wrote me, telling me that he was very impressed with the novel and that he wanted to invite me to Blanes. I had discovered Bolaño through the novel Estrella distante (1996; Eng. Distant Star, 2004), which I had read one year earlier, and it struck me as a tour de force, a real change of direction from the typical Chilean narrative of the time. That year, 1999, I had planned a trip to Europe, where I met up with Bolaño in Blanes and we became better friends, given how difficult it was to be Bolaño’s friend (laughter). I stayed in Blanes and saw his workplace, met his wife and children, and became closer to him. Thereafter, he was awarded the Rómulo Gallegos, and he invited me to give a speech to introduce him at the ceremony. So at that point we had already established a certain connection, but thereafter we were even closer. When he went to Chile for the second time, he was already battling with the Chilean milieu, and I did not see him, but later I returned to Blanes and our friendship became more solidified.

Beyond the friendship that I had with him, I found his attitude toward Chile very interesting. Bolaño was widely recognized in Chile and was invited by authors to be a part of the literary community and to join them at that table. But instead he said, “No, I am not interested. I am going to sit at another table, which is my own, and I am going to invite who I wish to my table.” That, of course, generated a tremendous reaction. It was a very interesting gesture because it was as if he were saying, “I am not striking a deal with anyone. I understand that I have not lived through the dictatorship nor the Transition, and that others have had their dealings with that, but I don’t have any reason to be a part of it. I am forming my own circle.” And to that circle he invited Lemebel, and several others, including me. It is with that group that he started to interact in Chile. Needless to say, that caused an enormous amount of criticism and repudiation. In the beginning, Bolaño got wrapped up in the war of words and fired back, but later, the storm settled, he became more tranquil, and knowing very well that his days were numbered, he focused completely on his work.

What Bolaño did was give form to the ruin of Latin America. He revealed it as no other had done. It didn’t exist before Bolaño. It existed in fragments in Piglia’s work, in some of Vargas Llosa’s pieces, and perhaps in Reinaldo Arenas.

I think that is the rundown on Bolaño’s relationship with Chile. Certainly there are many things that we could say about his work. In my opinion, his oeuvre is admirable, innovative, and necessary. Paradoxically, however, I think that it is the type of work that ignites, becomes red-hot, and, as he himself notes in one passage of Los detectives salvajes (1998; Eng. The Savage Detectives, 2007), suddenly flashes a brilliant light, then burns out for ages, to later reappear a second time, and then disappear once again. It is something that I have considered over a period of time, but it isn’t something that I have stated until now. Bolaño’s work can be considered characteristically avant-garde, particularly with regard to poetry, having a similar effect in history. From that perspective, Bolaño’s work is the cutting-edge counter to CADA and everything that happened in Chile at the time, but like all vanguardist waves, his is also destined to disappear from the scene not long after he appears, only to later reemerge. That is the figure of Bolaño—the warrior and the innovator. His poetry is like an infinite gesture, his oeuvre appearing and disappearing in endless cycles, telling the history of the great Latin American downfall. In that way, his work resembles [Alberto] Méndez’s, but of course much more massive and with an almost mythic breadth and depth, not to mention his iconoclastic touch and his encyclopedic style open to countless interpretations, but that always holds at its core the Latin American catastrophe. What Bolaño did was give form to the ruin of Latin America. He revealed it as no other had done. It didn’t exist before Bolaño. It existed in fragments in Piglia’s work, in some of Vargas Llosa’s pieces, and perhaps in Reinaldo Arenas. But the one who has breathed life into the history of Latin America as a whole, as an enormous catastrophe, is Bolaño.

PGC: Paradoxically, it is that vision of Latin America that has been honored by an incredible number of awards and translations and by the transnational editorial market. How can we reconcile these phenomena?

RB: That is the great paradox which currently characterizes Bolaño’s work as well as the larger Latin American defeated public to which Bolaño refers. How can that be? In part, it is because Bolaño’s work has that ability to recuperate those fragments among the ruins, much like we discussed earlier. He is able to effectively scrape the pot. He is concerned with memory and its active place in the present. To that end, he creates unpredictable characters and stories, such as the case of Amuleto (1999; Eng. Amuleto, 2006), which centers on a woman who finds herself locked inside a bathroom at the University of Mexico when the military laid siege to the campus; or Estrella distante, whose monstrous villain is a poet of the avant-garde. He takes an interest not in vindicating per se, but rather salvaging the remnants. On that account, the Latin American catastrophe to which his work gives life, in fact gives himself a chance to triumph, even though in the end it is impossible. Curiously, it was not until after his death that his project came to fruition. Upon his death, his work found its place in the spotlight, its path, and of course this happened for a variety of reasons, some of which are completely wrong and contrary to what Bolaño’s work is all about. What remains clear is that within Bolaño’s work there is a reexamination of [all] that. If you carefully read Los detectives salvajes, particularly the comings and goings in the second part—those characters in Israel, Africa, Barcelona, in unknown cafés—all those intertwining conversations leave tracks, or small traces of those characters, giving them the possibility to vindicate themselves, to finally be recognized and considered, suggesting that not all has been in vain. That is how I see it. If you read the speech that he made in Caracas upon receiving the Rómulo Gallegos, there too you find important clues to understanding not only his intentions but also his posthumous success. Once again the avant-garde character of his work and persona becomes visible; the recognition of the author trails behind his death, his disappearance.

PGC: Perhaps you could expand on that phrase you mentioned to us in a previous conversation: “All that relates to nationalism revolts me.” I would like to return to that theme, the narrative of the nation, and hear your thoughts regarding your personal decree as a foreigner and your distaste for nationalist discourses.

RB: Nationalism is a certain form of coercion. To be required to be Chilean or to be forced to resign to be Chilean. Why? I am what Chile has made me. Speaking of the difficulty or the impossibility of reconciliation, it is clear to me that Chile hinges on its own ability as a nation or as a community to truly perceive itself or not, to see a false reflection or a dark one, a real one. There is a controversy there concerning the relationship one has with the nation. It is formed through one’s initiation into history, through the storms that one experiences within that history, and through the national fictions that one is expected to reproduce. For that reason I say, “Be careful with what is national.” Whether it is my fiction or in daily life, I constantly grapple with the notion of the nation. That debate is always intertwined. It’s a conflict waiting to be resolved at some point. Why? Because it is the great originator of spite. The nation creates and personifies the place of bitterness, and trying to respond directly to that rancor is a mistake. One should try to grasp what that spite means, what the nation means, in a way in which one is no longer held captive by it. One of the greatest problems that we have in Latin America is spite, and it is simultaneously a big taboo. The state of the Latin American social fabric has developed a thick layer of resentment, so great that if one gets caught up in it, it is impossible to get out. As a writer, one should maintain a certain distance, and instead of reacting to that rancor, generate answers, respond to it. Rather than declaring war based on what the nation-state did or said, one has to maintain a certain equidistance. It is a rare intuition that I have and that I put into practice in an instinctual way, almost to protect myself. And I know that I have to maintain that position, within that uncertainty and equidistance in regard to the nation, and be mindful that there is a powerful poison there. Writers feed on poison, and so it is very dangerous to believe that in order to be a writer you have to take that poison. As a writer, I have to protect myself from that venom, particularly since it is so potent in Latin America. It is a great river like the Amazon. For me, it is always important to keep my finger on that pulse, gauging national and bitter indignation, and at the same time remaining watchful of any invitation to partake in that acrimony, to drink that venom and allow it to consume me. For me, that is the trap.

March 2011

Translation from the Spanish

By Lisa DiGiovanni