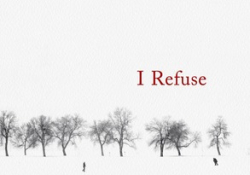

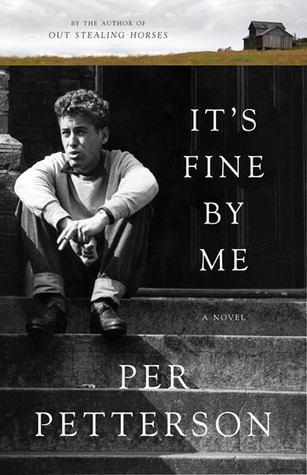

It’s Fine by Me by Per Petterson

Don Bartlett, tr. Minneapolis, Minnesota. Graywolf. 2012 (©2011). ISBN 9781555976262

Translated at last, Per Petterson’s second novel is a portrait of the artist as a young rebel. Its style and themes anticipate his later works while echoing the influences, chiefly London and Hemingway, that shape its first-person narrator and aspiring writer, Audun Sletten. As with all Petterson’s works, setting plays a vital role. This pre–oil boom Norway features the dwellings, bars, and factories of its marginalized workers alongside a resplendent, unspoiled nature, and its youth embrace American literature, music, and film.

Translated at last, Per Petterson’s second novel is a portrait of the artist as a young rebel. Its style and themes anticipate his later works while echoing the influences, chiefly London and Hemingway, that shape its first-person narrator and aspiring writer, Audun Sletten. As with all Petterson’s works, setting plays a vital role. This pre–oil boom Norway features the dwellings, bars, and factories of its marginalized workers alongside a resplendent, unspoiled nature, and its youth embrace American literature, music, and film.

Like the “unpurple” prose his best friend, Arvid, favors, Audun’s (Petterson’s) style is terse but lyrical. It distills both the noisy reality and sometimes-bloody consequences of the printing trade in which Audun works (having chosen to leave high school a year before graduation) and moments of preternatural beauty, as when a suddenly startled horse stuns Audun with its splendor.

Weaving between past and present tenses, Audun disrupts linearity with frequent flashbacks. Like Wordsworth’s “spots of time,” these illuminate insights and emotions that form the man he will become. We meet him first at thirteen, nervously attending his new school in the city to which his mother has moved her now-fatherless brood from their rural home. Audun embraces his “outsider” role, hiding himself behind his trademark dark glasses and the surly indifference his mantra embodies: “It’s fine by me.”

But as Arvid suggests, nothing is fine with him. For Audun’s hard-drinking father, all “black hair” and “gleaming blue eyes,” repeatedly promises love while inflicting physical and psychological cruelty until he abandons them completely. His absence haunts Audun, who feels fear, anger, and a deep longing for his love, rekindled each time his father briefly appears, his rucksack reflecting his choice to live alone in nature rather than wrapped in his family’s embrace. Yet this bag holds the clue from which Audun finally intuits that his father, like future Petterson father figures, battled the chronic pain of lost love. This realization transports Audun to the threshold of adulthood.

In fact, the novel examines literal and figurative fatherhood, exploring alternatives to Audun’s charismatic but dangerous dad. Arvid’s father lends the boys his car and good books, and while claiming to find him embarrassing, Arvid later reveals how much he loves him. Audun, meanwhile, having fled a traumatic scene with his father, is rescued after nearly drowning by a kind farmer, Leif, who oversees his weeklong convalescence. The gentle stroke of Leif’s rough hand on Audun’s cheek causes this “tough” kid to weep. So, too, “Old Abrahamsen,” a brusk, solitary former sailor, nurtures Audun back to health after a bad beating. Appropriately, Audun wears Abrahamsen’s old suit to his first job, the printing press. These surrogate fathers show Audun another way to manhood.

Along his journey from thirteen to eighteen, Audun upholds London’s proletarian writer and suicide, Martin Eden, as a beacon. But when at last Audun disavows him, we realize that Audun’s story resembles more closely the actual Petterson’s than the fictional Eden’s, and we can imagine Audun as the kind of writer Petterson becomes.

Michele Levy

North Carolina A&T University