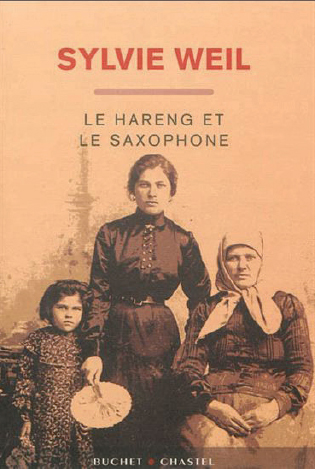

Le Hareng et le saxophone by Sylvie Weil

Paris. Buchet/Chastel. 2013. ISBN 9782283026274

Sylvie Weil has recently written a couple of fine books about family life, but in neither case are the families she describes conventional ones. In Chez les Weil (2009), she speaks about what it was like growing up in the shadow of her father, André Weil, one of the great mathematicians of the twentieth century, and of her aunt, Simone Weil, the philosopher and mystic.

Sylvie Weil has recently written a couple of fine books about family life, but in neither case are the families she describes conventional ones. In Chez les Weil (2009), she speaks about what it was like growing up in the shadow of her father, André Weil, one of the great mathematicians of the twentieth century, and of her aunt, Simone Weil, the philosopher and mystic.

In Le Hareng et le saxophone, she examines the family into which she married, an extended clan of Russian émigrés who settled in Brooklyn around the time of World War I. She traces that family in broad strokes across many of its generations, from the Ukrainian provincial city of Uman in the early 1800s to the present. The gaze that she casts upon it is a penetrating one, leavened by humor and by the fondness that she clearly feels for these people.

The focus of that gaze varies in interesting ways. In one perspective, Weil’s in-laws are exemplary of the phenomenon of European immigration and of the efforts of immigrants to find a place for themselves in American culture without sacrificing what they feel to be fundamental about their traditions and ways of being. In another perspective, they are absolutely distinctive, a family so utterly particular, so extravagant, that one might imagine it to be a pure figment.

Weil deploys those two modes of presentation adroitly, shuttling back and forth between the ordinary and the exotic, between the same and the different. One of the more intriguing aspects of her account is couched in muted terms. It involves Weil’s efforts to understand her husband’s family, and the way those efforts sharpen her perception of her own situation as an immigrant, as someone who has left one kind of life behind in order to live another. Indeed, this book is as much about Weil herself as it is about her husband’s family, yet that autobiographical dimension is very tactful, as if the teller of this tale were only reluctantly a part of the told.

Warren Motte

University of Colorado