Comics, War, and Ordinary Miracles

After meeting at a short-fiction conference, Adnan Mahmutović and Lucy Durneen began talking to one another about his childhood love of comics and his efforts to preserve them during the Bosnian War (1992–95). Durneen encouraged Mahmutović to write an essay about these experiences and, inspired by their conversation, wrote a connected though independent story of her own. Here they join the two, creating a hybrid essay that braids together their two histories. Ultimately the two connect through friendship and the importance of preserving our most miraculous stories.

How to Save Comics in Times of War

by Adnan Mahmutović

When the war in the Balkans started, my best friend Armin and I were so worried the soldiers would destroy our comics that we started thinking of the best places to hide them before we had to leave the country, so if we ever came back we’d find them well preserved, or at least in the shape of smelly and exotic artifacts like old scrolls from Indiana Jones.

I guess that’s the kind of crazy shit two pubescent geeks would do when they couldn’t even get one mercy fuck in a time when everyone else was doing it. War was the best excuse for premarital sex, and girls were easily agreeing to shorter dating periods before giving in. But it was usually the girls who took charge of that, the sex, because most boys, geeks or normal, were so hopeless even sex instructors would need to give them extra help to pass the exams. Except we didn’t have sex education in 1990s Bosnia. Until I came to Sweden, I thought sex education was just this utopian idea Monty Python made fun of. By the time I got to this sexy Nordic country, I was too old, and the only class I had for two years was Swedish for beginners—populated by my parents and uncles and aunts and other such types. Mind you, I wasn’t entirely hopeless. I did have a girlfriend those last few months before we left on refugee buses, but we never went that far.

But let’s move beyond sex to more important things. Comics. The Balkans were huge on comics. We imported everything and anything, from expensive Marvel and DC to cheap Italian pulp. Armin and I usually bought secondhand Italian fumetti stuff from a big fat gypsy who sat all day outside some municipal building in central Banja Luka, right across from the shopping mall Boska, where my mother got a job after eight years in the cellophane factory Incel. Cigo, as we called him, was on my way from Metalska Škola to the bus stop from where I’d take bus number 3 or 3C or 3D to the suburb Vrbanja. Since my mother bought me more comics than Armin’s mother did for him, he’d borrow mine all the time, especially the new albums by Balkan stars like Igor Kordej. Some of those I only let him read in my house. He still holds a grudge for that, but then I was afraid that his father would burn them when he was mad at Armin. I’d seen him do it, so I couldn’t take the risk.

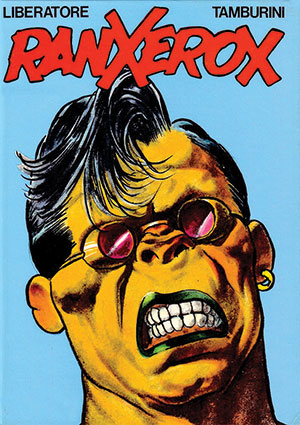

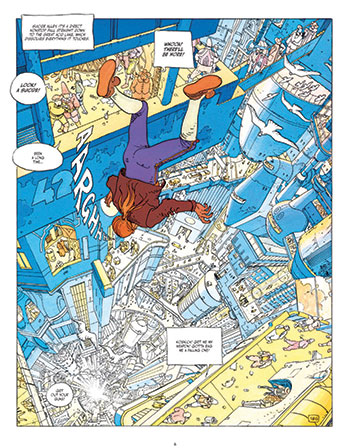

Our major development happened in the year before the war, and it wasn’t hormonal. We started reading amazing French and Belgian stuff, underground comics, people like Moebius and Bilal, the Italians; yes, dear Lord, Liberatore and Pratt were awesome. Armin resisted Hugo Pratt for quite a long time because he loved the artists who were more into anatomically correct drawings, and all the great stylists were not his cup of tea (I should say coffee because he hated tea). He said Pratt couldn’t draw a lemon to save his life, but due to my implanting a love of Pratt in his mind, years later, Corto Maltese became his absolute favorite, and the reason why he loves Hemingway. Dear God, those were some seriously disturbing works. Now that I think of it, when I read books or watch films with my children, I tend to consider what may or may not be appropriate for them, but back then such censure was nonexistent. I still can’t believe that we, as fifteen-year-olds, enjoyed that extremely political stuff like Bilal and Christin’s Black Order Brigade and The Hunting Party, or the six-volume The Incal, the stunning philosophical-sci-fi-crime-drama by Alejandro Jodorowsky and Moebius. I’d be very surprised if my kids ever picked up things like that, comics that were darker, more serious, and more controversial than any of the books we’d read at school. I mean, just remember (as if forgetting was ever an option) that scene from RanXerox when the main character crushes a flower girl’s hand when she approaches him in an Italian café. My mother never questioned what she was buying me. Ha! So cool to finally find a thing I don’t feel like blaming her for. Eat that, Freud.

We read very little Marvel and DC back then, partly because we didn’t much like anything except Jack Kirby and John Buscema’s stuff. The Americans we loved were Milton Caniff and Will Eisner, and for a while even that fascist Frank Miller (because we didn’t know better). I was really into this Belgian thriller series XIII, by Jean Van Hamme, which I found in Paprikovac Hospital when I had hepatitis. Someone had spilled orange juice on it and the black-and-white pages were now appropriately yellow, like my face, but that didn’t matter. I’d read it thirty times by the time I was out.

I could go on dropping names all day long, but I want to tell you about the miracle that happened right at the beginning of the war. You see, miracles have serious timing issues. We found paradise in central Banja Luka, close to Mala Čaršija. It was a room in an old-style Bosnian house that belonged to Sejo. I can’t remember his surname now. He was an urban legend among geeks, but we only heard it quite late, probably because we were too geeky for the geeks. Never mind. They said Sejo had a collection of all comics ever published in the Balkans. Lock, stock, and barrel. Everything under the Balkan sun. He may not have read all that stuff, they said, but he was a collector par excellence. I found out where his house was, and I decided to go there one morning, quite early, before he left for work. He was a translator and letterer in the comics publishing industry. At that time the Yugoslav army had already put several checkpoints around the inner-city circle, and since we lived in the suburbs, I put a bag of cornflower on my bike, pretending I was driving it to a customer. I’d heard the soldiers didn’t always harass younger children and women selling food in the city. When they stopped me, I didn’t say much. I’ve always looked younger than I was, so they didn’t ask for an ID. They checked the bag, and, finding no contraband, they let me go.

It was so cold that morning I stood at the tall wooden gate to Sejo’s house. Knocked. No answer. Then I jumped over it, and the moment I landed in the backyard, this short, chubby man grunted something.

I stuttered my explanation why I was there, and he said, Yes, I’m him. But I don’t lend comics to anyone. People have stolen a lot from me. Even now the guy that sits there—he pointed toward the street in Mala Čaršija (not Cigo)—is selling a bunch of my books.

I’d never steal from you, I said. My friend and I are just tired of reading the same few books we have. We wonder if you have the new Druuna series. We heard it’s awesome. (Druuna was an amazing erotic series with a big-busted protagonist walking naked in a sort of post-apocalyptic setting in which everyone was infected and turning into a horny monster. Lots of disturbing sex with monsters.)

I do, he said.

I couldn’t believe it. It must have been one of the last translated works before the war pressed pause on the industry.

May I see it?

Not today.

When?

We’ll see. You have to prove yourself worthy. (I don’t think those were his actual words, but it sounded as if I were Thor, trying to be worthy of wielding his Mjölnir.)

I will.

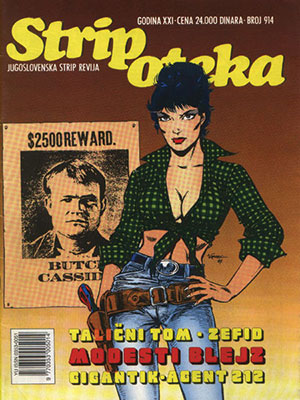

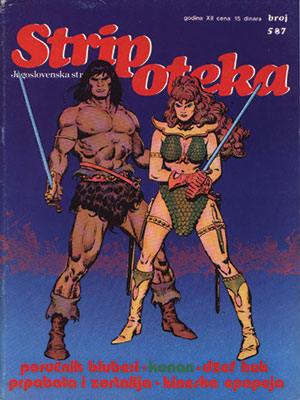

He didn’t let me into paradise that day. He brought out a few issues of a magazine called Stripoteka, which collected shorter pieces or serialized graphic novels before they were published as albums.

God, they smelled so old. Amazing. Let me say it again: amazing and old and smelly. Either he had never opened them or, if he did, he must have ironed the pages after reading them and put them back in their predestined place.

I told Armin all about it, but next time I went to see Sejo, the following morning, I didn’t bring Armin with me. Sejo let me sit in that small room in which not an inch of wall was visible. I was spinning in my mind like in The Sound of Music. Freedom of closed spaces. Talk about slow-motion mind-set, experiencing the world like a fly, like Neo (though The Matrix wasn’t even a sperm, I mean a germ, in the Wachowskis’ minds). Sejo’s wife even made me a turkey sandwich with ajvar. It was too spicy, the ajvar. The next time I remembered to bring her a box of raspberries, which my family grew and sold to the Vitaminka jam factory. She was the kind of woman who talked a lot about eating healthy, organic food, and now that I think of it, she must have been my first vegetarian friend. I’d never seen her eat meat. I had to eat my sandwich in the kitchen and then wash my hands, not to destroy the comics with my fatty fingers.

Did I do everything to make Armin jealous? You bet. The way I painted it to him, forget about the houris they say are reserved for martyrs in the Muslim afterlife. Those untouched comics were worth getting killed by the soldiers.

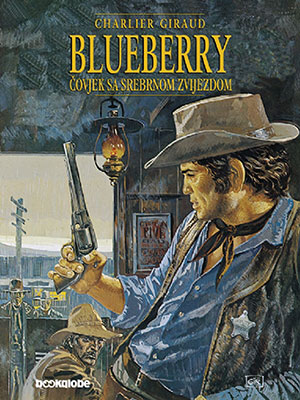

One week later, when I’d proved myself worthy, Sejo let me bring over Armin too, and later he even started lending us books, but mostly because he didn’t want us coming in every day and passing those checkpoints. We told him the soldiers were starting to get suspicious, especially on the days we forgot to bring cheese or flour or whatever else we pretended to be selling in the city. So he let us take dozens at a time, and we were not supposed to return for more until at least five days had passed. That was painful. We finished them in a day and reread and reread, and then we spent four days worrying that, since the war was escalating, at that rate we’d never make it through the rest of the books before we died. At first, Sejo lent us the books we didn’t even want to read, but it was important for him that we followed the chronology, not of the different series, but of the publication. So we had to read everything in order to earn our way to the books we really wanted to read, like all the Blueberry issues.

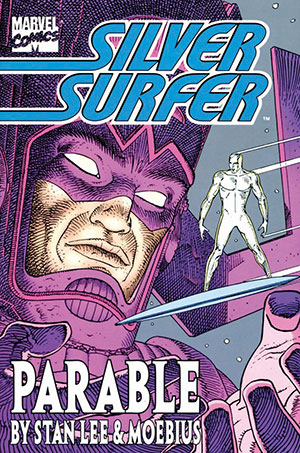

I found that he had a copy of the extremely limited edition of the special issue of the Silver Surfer called Parable. I’d only heard rumors about that phantom book and couldn’t believe I found the Holy Grail already translated and printed and stored on one of Sejo’s shelves. He hadn’t even read it. Blasphemy.

Then Sejo left for Sweden. His daughter had escaped on one of the first convoys and was already sending her parents Red Cross messages. She was describing the refugee camp in Vårgårda, where I too would one day come, this pristine little place covered in snow and untouched by man or immigrant. That would turn out to be bullshit, but helenejse never mind. Sejo was really sad to be leaving, but he had been tortured by the soldiers a few times in the Little Camp, as they then called this place where they used to take men randomly picked off the streets and beat them up. I was so worried that I’d never make it to the books Armin and I were dying to dig into. But Sejo’s wife promised she’d let us borrow as much as we wanted. Her task was now to try and smuggle out her husband’s collection to Sweden before their house was taken from them and she, too, had to leave.

Once Sejo left, we didn’t have to follow the chronology of publishing. And this is what happened. I took all the Druuna albums and decided I would smuggle them out when we boarded those refugee buses. Stealing is not stealing if your intentions are good, right? That wasn’t all, and that wasn’t the first time I stole from him. Before he left I found that he had a copy of the extremely limited edition of the special issue of the Silver Surfer called Parable, which was a collaboration between Stan Lee and Moebius. I’d only heard rumors about that phantom book and couldn’t believe I found the Holy Grail already translated and printed and stored on one of Sejo’s shelves. He hadn’t even read it. Blasphemy. I was furious. I wanted it so bad, but he didn’t want to lend it to us, so I shoved it under my jacket one time he went to the bathroom. Later I told Armin I’d bought it from a dealer I’d found. Armin was suspicious, of course, but he wanted it as badly, and now it was ours. So beautiful. So philosophical, we thought. So hopeful and romantic. The soaring, suffering soul of the Silver Surfer as he tries to save humanity from Galactus radiated from those shiny pages. Ecstasy. Worthy of putting up with abundant assonant and alliterated praise, don’t you think. The only other book I loved that much at that time was Joe Kubert’s Abraham Stone.

The war was getting nastier, but Armin and I weren’t afraid. We’d drive around on our bikes as if the infamous Red Van wasn’t roaming around looking for nice punching bags. If the weather was nice, I’d help Armin take his two goats high up onto the mountain where we’d talk comics and even try to learn English to be able to read an awesome edition of The Fantastic Four from the 1960s that Sejo gave us (he really did). Jack Kirby at his best.

I poured old engine oil into a lamp and used it at night in the attic. The walls were black, and I’d cough but couldn’t stop reading.

Did I say we had no fear? I lied. We feared for our comics so much I’d deplete my father’s car battery to which I’d connected a small bulb to read my books over and over until I’d memorized every page. The power cuts were too long, and it was hard to find ways to recharge the battery. The small river turbines we made didn’t always work. I poured old engine oil into a lamp and used it at night in the attic. The walls were black, and I’d cough but couldn’t stop reading.

So how did we save our collections? We loaded them on a wheelbarrow and went to a shed Armin’s family had in the woods somewhere on the mountain, but when we got there, we realized that place could be blown away by a big bad wolf and our poor little comics would be destroyed or, God forbid, eaten up by wild beasts. So we tried a few other equally silly plans, and the people in the streets would watch us like the freaks we were, pushing that wheelbarrow up and down the street, looking for the best hiding place. Grown-ups were burying gold and such stuff. My mother buried some, and she never found it after the war. I think my uncle buried a VCR. I came up with the idea to pack the books in waterproof bags and sink them all into a septic tank. The soldiers wouldn’t check the shit hole, right? We did that, and then, since it’d take a few more months before we actually became refugees, I was getting so annoyed because I couldn’t read my comics, and I had a sneaking suspicion the bags were not as shit-proof as I thought they’d be, so I retrieved them from the septic tank. Let’s say my gut feeling was correct. I had to use up an entire bottle of my mother’s expensive deodorant to kill the smell. And, believe it or not, Mother wanted to kill me. When we finally became refugees, I saved a few comic books, including Sejo’s Druuna albums and the Silver Surfer.

I remember being so happy I was becoming a refugee and hoping to end up in a country that had loads of comics. When I came to Sweden, my first camp was Vårgårda, where Sejo’s daughter used to be, but it was a transitional camp, and we moved to Uddevalla on the beautiful West Coast. That’s where I met Sejo’s daughter and her boyfriend/fiancé. It took me a while to tell her about the albums I’d stolen. I told her that I would return them to her father. And I did. But not the Silver Surfer. No, sir; I was still mad at Sejo because he hadn’t cared to read it. Only a few years later, when I became a bit religious and felt the burden of that big heist, did I find Sejo’s address and give back the Surfer, which was now falling apart from all the reading, with a note asking his forgiveness for my sins. Never got an answer. I met him years later at one of those big gatherings for people from the same city, the Banja Luka Club, and he talked about all the books he didn’t manage to save, but he didn’t say a word about my theft.

Now, I have a large collection myself. No chronology of publishing, just the best editions of the books I love the most. I have a standing 20 percent discount in Comics’ Haven in the Old Town in Stockholm. I have put comics on almost all my syllabi at the Department of English at Stockholm University, and my dream is to one day become a comic book character, drawn by Joe Sacco, or Moebius, or Bilal, or by the ghost of the old man Pratt. And yet, however great they look, those Bible-like absolute editions of Sandman and Incal and the Nicopol Trilogy, those stunning prints of Maus and Meta-Maus and Safe Area Goražde and Footnotes from Gaza, those ultimate-geek-editions of Watchmen and V for Vendetta and All-Star Superman, I have to say that nothing I’ve read after I’d escaped Bosnia, not even those same comics that gave me so much pleasure, have felt as good as reading in my cold attic, breathing smoke of burning engine oil, Yugoslav army soldiers driving by and shooting at houses and religious buildings. No, nothing beats reading comics in wartime.

Stockholm

Everything I know about comic books* (*and what I am afraid to ask)

by Lucy Durneen

You’re in Forbidden Planet on Burleigh Street, Cambridge, the new, improved store, the world’s number one for your comic book needs. This is good, because you’ve got a comic book need. Up until last year, Forbidden Planet was a hushed place on the other side of the street; crossing the threshold was more an admission of something than an intent to purchase. But this new store is a clean, well-lighted place, and inside, flicking through the browsers of graphic novels, you want to belong. You gaze at the high shelves, the acreage of stories. Some titles are familiar, most not. By familiar you mean the ones with characters your kids wear on their pajamas.

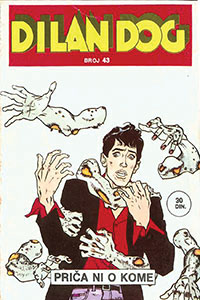

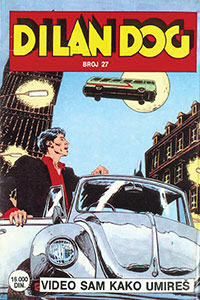

Your plan is to look like you know what you’re doing, because that’s what Indiana Jones would do. So when you approach the desk to ask for help in tracking down early 1990s Bonelli—but not the Italian ones, the ones from the former Yugoslavia—you assume the casual, professional air of a true collector. What? This is the way you always spend your lunch breaks. No time for love, Doctor Jones.

The assistants at the counter look at you and their beards twitch. What’s wrong with Marvel? they want to know. But the word you have fixed on is Bonelli, so you shake your head as if you’re disappointed by their lack of knowledge. It has to be early ’90s, you say. Really, it has to be from 1992. It has to be from—you find yourself getting tangled up in the geography. The Balkans, you say in the end. You might as well have said Mars. They turn back to setting up a little diorama of Minecraft merchandise. They don’t even bother to shake their heads. Try the Internet, one of them says.

The Internet–where everything and nothing is possible. Like you hadn’t already thought of that.

In the summer of 1992, an almost-fifteen-year-old girl and her best friend went to the annual Strawberry Fair in Cambridge, England. The girl thought maybe they would ride the waltzer and pretend to drink lemon hooch with the kids she hoped might stop giving her a hard time if she acted a little more like them. Instead, outside a dirty canvas tent she found a bucket of goldfish waiting to be transferred to the cellophane globes on the nearby Hook a Duck stand. The fish looked sad, a seething mass of orange like a solar explosion in a plastic tub. The girl and her friend glanced around, picked up the unattended bucket, and walked fast until they were two streets away from the fair, water surging over the bucket’s lip at every step and soaking the toes of their Doc Marten eight-holes.

The girl was kind of lonely. She read a lot. Too much. The other girls in her class were pretty and were learning how to kiss the boys in the dark of the school drama theater. The boys in her class made vomiting sounds when they played spin the bottle and the bottle stopped on her. Somewhere around the beginning of 1992 she had decided to stop eating, as if loneliness and food were connected somehow and she could fix one by rationing the other.

The girl watched Tintin on Sunday mornings and scared herself with The Twilight Zone, and that was about as much as she knew about comic books. By the summer of 1992, she hadn’t eaten anything except cabbage cooked in vegetable stock for nearly four months. She had a crush on Cyrano de Bergerac. Partly this was because of Gérard Depardieu, who hadn’t yet gotten fat and started pissing in planes, but partly because she still half-believed in the existence of heroes that didn’t look like heroes, the ones who maybe were okay about it if you got good grades and wrote poems and didn’t have big boobs or straight teeth.

One time the girl’s mother threw a plate of food at her and shouted, Why can’t you just be normal? And she really wanted to know. The girl’s father was in the business of reconnaissance. She hadn’t seen him for some months. In summer 1992 she didn’t actually know where he was, other than that a war in a place that was no longer Yugoslavia had taken him away.

Eventually, officially, wars come to an end. Some people get to go back home, like the girl’s father. Mostly war follows you, invisibly, internally. You can make it your business to study the writing of war, but there is always the knowledge, a deep guilt in the regolith of you, that no matter how much you read you can never, actually, know. Lives converge until the moment they absolutely don’t.

A boy and his best friend pushed a wheelbarrow full of comic books into the mountains above the Bosnian city of Banja Luka to try and hide them from soldiers.

In the summer of 1992, or thereabouts, another thing was happening, something the girl only hears about more than two decades later, via Facebook messenger. A boy and his best friend pushed a wheelbarrow full of comic books into the mountains above the Bosnian city of Banja Luka to try and hide them from soldiers. Afraid that wild animals would destroy them, they came up with a different plan. Wrapping the comics in plastic bags, they lowered them to safety in a septic tank, only to realize some time later that the bags might not actually be shit-proof after all. It turned out this was indeed the case. The comics were retrieved. The boy used up a whole can of his mother’s expensive deodorant to take away the smell. His mother wanted to kill him. His words.

Twenty-two years later, the boy, now the girl’s friend, writes to her and says, I was really stupid, wasn’t I?

The girl, you, says, No, and it’s not entirely a lie. It’s what Indiana Jones would do.

That’s how little I was worried about being killed, he says. Bloody geek.

But geeks are so much cooler than nerds.

What?

Sorry. I thought that was my inside voice.

Your eldest son is a proud Doctor Who geek, and inordinately fond of that viral song “Dumb Ways to Die.” He worries a lot about being killed. By solar flare, freak asteroid impact, zombie apocalypse, Ebola. You try to imagine him navigating checkpoints, hiding his stuff from soldiers, and remember how last time he made lunch for himself he used a tea strainer to drain a can of tuna fish.

When your friend tells you about the comic books in the septic tank, it’s like you are watching the scene in a snow globe, or Asimov’s chronoscope, these two kids and their wheelbarrow going up one street and down another, their frustration growing, and perhaps also their fear, but he doesn’t mention that. Somewhere in this is a need to change something. If you could shout down through the time vortex. If he could look up into the ether to see you waving. What would you say? Throw me your comics, I’ll keep them safe for you? Or—hang on, I’m coming down, let me help push the damn wheelbarrow? A nerdy girl, you think, might have come up with a better plan than a septic tank.

He sends you an essay to read, something he wrote after you met in Vienna last summer. It’s about faith and forgiveness. Here you see he’s ambivalent about forgiving a person who once stole his collection of Bonelli comics. He’s joking, sure, but—here are those comic books again, you think. They really do mean something.

You read the essay about ten times. You want to ask so many things. Bonelli, it says. Bonelli. Italian. You commit it to memory, which is a less esoteric way of saying it starts to haunt you. You think of that story about Hadley Hemingway, the famous one in which she catches a train to visit Ernest in Lausanne and while waiting at the Gare de Lyon her suitcase containing every last one of the original Nick Adams stories is stolen. You imagine the despair of knowing there is nothing to replace the thing you have lost, an emptiness that stretches out about as long as the journey to Switzerland.

When the idea comes to you, it comes the way anything obvious and also impossible arrives in your mind. You’re going to replace those ruined comics. You know nothing about Bonelli, but by some chance, you do count among your acquaintances a few magical agents and allies. You ask around the Victorian halls of the Cambridge School of Art, geeks, collectors, experts on graphic literature, but this one seems out of even their league. Someone knows someone somewhere in Slovenia who maybe once had a thing about comic books. Will that help?

It doesn’t. That’s how you end up in Forbidden Planet talking to assistants with twitchy beards who’d rather sell you the latest Spider-Man.

•

chronicled in a series of the same name by Hugo Pratt.

When you said you know nothing about comic books, this is not entirely true. It’s just that you’re not talking your Silver Surfer or Blueberry. You’re definitely not talking Corto Maltese.

There was a time when you and your friend Sarah were avid devotees of the Just Seventeen photo story, which is to say that you were romantics who had not yet experienced romance and were educating yourself on mildly erotic, post-punk tales of attraction featuring bad boys in leather jackets, which explains a lot about your respective emotional crises to come. On one occasion, planning a surreptitious photo shoot, you went to the town library in fishnet stockings and heels stolen from your mothers’ wardrobes; you barely made it through the door before the librarians asked to see your borrowing cards (which you dutifully handed over) and promptly called your parents to come remove you, your artistic intentions crushed.

That was the end of the photo shoots. But you’d caught the storytelling bug, you and Sarah, the vice that Hemingway says only death can stop. There was a time when you wrote and illustrated Choose Your Own Adventure strips, in first one and then a series of identical red exercise books: the destined-to-be-legendary Red Book Choice Story, which one of you still owns in an attic somewhere. That book was pretty dangerous. In it you made good stuff happen to people you liked, the teachers who were kind and didn’t throw chairs. You brought to life rumors of affairs and made the cool fifth formers fall in love with you. You gave the mean kids their comeuppance. It was secret, of course, until one day it wasn’t. As stories went, it was a page-turner, and it was gaining an underground reputation. Then Katie (not her real name) asked to read it. Katie was someone who took a persistent, vindictive delight in flipping up your netball skirt to reveal those blue regulation gym knickers, and let’s just say her narrative arc hadn’t ended well. Turn to page 48 to avenge the wrath of the schoolgirl demon. Still, she scared you enough you didn’t know how to refuse.

One thing you don’t know for certain: if it came to it, if you had to, how much would you really have risked to save that book?

Here was the solution: you sat up all night to rewrite that book, the book that for months had demanded a more organic, defiant kind of evolution. When you think of it now you wonder about the way you didn’t stand up for the words. You want to believe this was what was needed to save the story (and your good-girl reputations), a mild form of literary collateral damage—but this is not how it feels. Now it feels something closer to cowardice. Barthes says that the book creates meaning and then that meaning creates life. If so, then the meaning you were creating wasn’t shit-proof. One thing you don’t know for certain: if it came to it, if you had to, how much would you really have risked to save that book? In the snow globe, what you see is disappointing: two girls doing nothing but covering their steps.

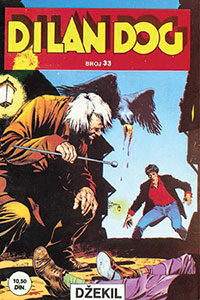

But the thing about Choose Your Own Adventure is this: for every dead end, there is a way to renegotiate fate. A rope-bridge you didn’t notice on page 61 leads you to safety across a gorge. As you are leaving Forbidden Planet, some guy comes up to you. He taps your sleeve and asks, What are you after? Dylan Dog? Martin Mystery? And immediately you understand that he heard your conversation with the twitchy beards, that by some osmosis he senses the vital nature of whatever it is you’re trying to do. Here is your improbable reprieve, arriving like an angel with the correct vocabulary and everything.

You tell him you actually have no idea what you are after. It’s a relief to confess it. You tell him the story of the comics in the septic tank. You tell him how you want to replace those shit-stained comics, the ones that never made it to safety in Sweden, which is where your friend ended up after the war. As you talk you realize how many gaps there are in what you know, what you’re doing, but you learn this: strangers are so happy to help what they think of as a romantic (by which you mean old-school escapist, wild–and, yes, crazy) notion. He pats you on the arm as if you’re in need of Valium. Okay, he says. Okay.

The guy has a friend in Sarajevo who might be able to help. He takes your email address. The synchronicity buoys you up. It’s like you’re in a real comic book world of mystery and clues and leads. You don’t say anything to your friend. You think you’ll send him the comics for his birthday. It occurs to you that you don’t know when his birthday is. Seriously, you don’t have any idea what you are doing.

What part of the human brain compels it to see everything in relative terms? It doesn’t even have to be the dramatic stuff. You understand how pattern finding has a deep, biological appeal. As soon as you heard the story of the comics in the septic tank, your own history became relative. You don’t mean less. “The far becomes the near,” says Rebecca Solnit. Things braid together in a new way; for a short time the only thing you could see, like a retina burn, was a teenage boy and his best friend sinking a plastic-wrapped bundle of comics into a stinking shit-hole while on the other side of the continent a teenage girl and her best friend, both with a labyrinth-sized crush on David Bowie, repeat-pause VHS tapes on the dance scene where the Goblin King’s crotch earns a credit all to itself.

About six years after the comics were hidden in the septic tank, you spent a summer working as an intern in the department of prints and drawings in the Musée des Beaux Arts, Brussels. This was the summer you learned to eat again. You didn’t know it was going to work this way, but standing in the great hall looking at Bruegel’s Icarus, that all turned out to be part of the recovery.

W. H. Auden wrote a poem about that painting:

About suffering they were never wrong,

the Old Masters. How well they understood

its human position: how it takes place

while someone else is eating or opening a window.

So many people saw your friend and his friend pushing a wheelbarrow of comic books around town, but even in war, everyone has somewhere to get to.

The sun shone as it had to, says Auden.

Perhaps one of the quiet tragedies of being human is that mostly, no one is looking. They don’t see something amazing. They see Icarus’s legs disappearing into water and what they do is open a window. Here is what starts to get braided together then: the safety of your life and the danger in his. The way you were (not) eating or opening a window; the way he stuck two fingers up at that danger, leapt over the gate of a comic book collector in inner-city Banja Luka and, in defiance, entered an adventure illustrated with invincible superheroes and big-busted apocalyptic monster women, a Promised Land. Icarus flying for the sun.

•

A few days later you hear from the Forbidden Planet guy’s Sarajevo friend. Your emails muddle by in a mix of pretty bad English and rusty German, which is the best you can muster between you. He tells you that he has plenty of comics from the late 2000s, but anything from the ’90s is impossible to get hold of; those books are like, well, gold dust. You explain to him, in very general terms—because it’s still hard to explain to yourself, to anyone, in complex terms—why it’s important. Minutes pass. Wait a moment, he types. Write you a new mail soon!

He gets back to you later that evening. You know these are not English language? he says, as if things can’t proceed until this has been established. These comics are in the Croatian language.

You ask if it’s possible to get them in Bosnian. His reply is a series of bewildered exclamation and question marks, and suddenly you realize a comic book is not just a comic book, that language is not just words uttered, that what you thought was knowledge is in fact just a haze, a silvered approximation of a war.

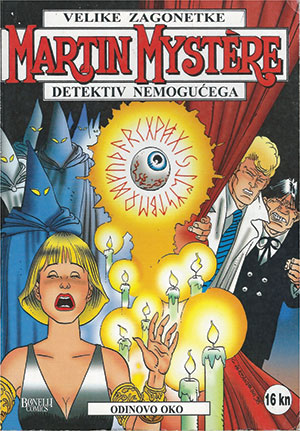

He sends you what appears to be a 1998 Marti Misterija, in Croatian, and says it’s the best he can do; he can’t get earlier. But he also has a whole bunch of Dylan Dogs and an Alan Ford, which is his personal favorite. He’ll send those, too. Registered fast packet, he says. Important! You lack the real words to show your gratitude, even though a tiny part of you is disappointed that you couldn’t get what you really wanted, whatever that was. Hvala doesn’t quite cut it. In English he writes that he has all (yes, all) the Martin Mystery series from the beginning to a few years ago when he stopped collecting. There are not coming so many new . . . he says, and you feel the ache in the ellipsis. You don’t ask why he stopped collecting. You are still thinking about the currency of these books. The way they might matter so much that a boy would risk his life to keep them safe, or that grown men would smuggle them to refugee camps. They must be fucking awesome, you think.

There’s a giant eyeball on the cover of the Martin Mystery. Inside, naked girls in some kind of swirling continuum. This MM is an art historian, adventurer, anthropologist, and collector of unusual objects. You had me at art historian! you want to shout. A comic book hero who is part nerd! When they arrive, when you pore over them, in a language you can’t read so you have to navigate through image alone, it is their ordinariness, the intimate, insular relationship they set up with their reader, that really breaks your heart. Only later do you realize what has been lost in translation—this is in fact a reissue, not as old as you thought. There are not coming so many new. A glacier shifts, the rope bridge breaks, and the path of this adventure comes to an end.

There’s a giant eyeball on the cover of the Martin Mystery. Inside, naked girls in some kind of swirling continuum. This MM is an art historian, adventurer, anthropologist, and collector of unusual objects. You had me at art historian! you want to shout. A comic book hero who is part nerd! When they arrive, when you pore over them, in a language you can’t read so you have to navigate through image alone, it is their ordinariness, the intimate, insular relationship they set up with their reader, that really breaks your heart. Only later do you realize what has been lost in translation—this is in fact a reissue, not as old as you thought. There are not coming so many new. A glacier shifts, the rope bridge breaks, and the path of this adventure comes to an end.

What changes the world is the private wars people fight. Something amazing is the boys on the mountain, affording these stories of doomsdays and utopias the same status as diamonds and gold.

This much you know. What changes the world is the private wars people fight. Something amazing is the boys on the mountain, affording these stories of doomsdays and utopias the same status as diamonds and gold.

The war your father fought was in the air and it was public, and complicated. When your father returned from the Balkans he was a different man. Or maybe you were a different daughter and saw things you hadn’t understood on his return from previous detachments: East Germany, Iraq. Lost, is the way you would describe him. Redrawn. Something your father heard in one town: a man had cut the head off his neighbor, a former friend, someone whose plants he had tended and whose dogs he had fed, and put it on a spike in his front garden. Above another town, a light attack aircraft was downed and the pilot ejected. He was found, mortally injured, by Ustase militia, who took him away, beat him to death, and mutilated his already-wounded body.

A week or so later, your Sarajevo contact emails out of the blue to say he’s been thinking. He might have something for you. He’s actually got pretty much every comic out there, but he won’t sell. What he will do is scan them and put some on DVD. Any ones you like.

There is something in this offer, this considered, delayed response, the desire to help flashed through with the desire to preserve the integrity of his collection at all costs, that makes you feel sad and simultaneously connected to something. Such generosity among an underground network of geeks. Your only tangible experience of Bosnia is this, comic books that form a chain across, under, around Europe. Stories defying borders where people can’t, people who will do whatever they must to restore the gaps in the narrative.

Once a semester you and your colleague Caron host an open-mic poetry night where you encourage your students to read and perform their own work. Some of them are a little bit afraid of poetry, but the camaraderie, the free wine, and the craic fix that. You stand at the front of the lecture hall backlit by a PowerPoint that reads, Words Have Power. Words are smuggled from concentration camps, you tell them, through border posts, over mountains. Words are swallowed and remembered and burned into us in order that they survive. This is why we do what we do. This is why we write. This is why we read. Sometimes you worry whether this means anything to twenty-first-century teenagers whose biggest concerns, the media claim, involve thigh gaps and who their favorite celebrity is sleeping with. Then someone stands up, the quiet kid at the back who hasn’t spoken yet, and reads about how his father is in prison for murdering his brother, and you realize that it’s not just the words that survive; we risk everything for them so that the strongest parts of ourselves will too.

That’s how little I was afraid of being killed.

You’re not sure if you believe your friend when he says this. But then, you know this to be true enough: on the only occasion you can say you were truly in grave and immediate danger of dying, you were pathologically practical. Half-mad with pain and morphine, you made arrangements with the theater nurse, who humored you by taking real notes, to cover your postgraduate dissertation supervision for a week. You told the anesthetist that under no circumstances was he to have an argument with the surgeon over the aforementioned nurse if you went into VF, the way they did on the hospital shows. It’s okay, he said, we’re all happily married here. Then he pressed down on your windpipe to stop your stomach contents entering your lungs and put you under. You had no intention of dying, although the odds at the time were relatively high. You didn’t even know what VF meant. What you’re really saying is that maybe in the face of danger, we assume a hero’s level of pragmatism, a clear ability to compartmentalize what is being risked away from what is needed, what is desired. It’s possible this qualifies as a superpower.

You don’t write back straightaway to the Sarajevo guy. You’re not quite sure what you’d be asking for. A DVD doesn’t seem the same somehow. It’s the tangible object, the restoration—the sheer materiality of your quest—that has been driving you, the book nerd’s fantasy of the longed-for manuscript pressed into the outstretched hand. If you could travel to the afterlife and present Hemingway with a DVD of those stories from the suitcase stolen at the Gare de Lyon, you’re pretty sure he would throw a daiquiri in your face.

The weather is turning cold. One day your friend messages to tell you he wrote an essay on how to save comic books in time of war. He did it because you told him to. There’s more to the story than what’s in your snow globe. More than the wheelbarrow and the septic tank.

You’re about to give an undergraduate writing class on constructing character. You’re planning to do an exercise that draws on Tim O’Brien’s story “The Things They Carried” because you want your students to leave behind the trappings of their own autobiographies, just for a moment. Instead, at the very last minute, you ditch the schedule and tell them the true story of the boy who hid his comics in the septic tank. You watch your students’ faces change. Even the two at the back who have been talking about the work they haven’t done for their Renaissance drama module are listening. Sharp winter light streams through the windows.

Even now you have not told your friend what you’ve been doing. Part of you is a little embarrassed. You experience what you come to think of as a distant cousin of survivor’s guilt, but it’s a superlative guilt that recycles and reactivates itself, guilty twice over—once for the simple fact that you didn’t suffer his suffering, and again for its own fraudulent act of existing; this isn’t even authentic; you survived nothing; it’s survivor’s guilt by proxy. Maybe this is your ouroboros come to get you. Damn it.

Still, in your tea break, you go back to your stuffy office and write your friend the pathetic story of how you tried and failed to hunt down his comics. You hesitate, just for a moment, before pressing send. You’re worried he will think badly of you, that he will think you stupid for believing that replacing a comic book might heal the other kinds of wounds that war leaves a person with, the ones your friendship is too new, too distant to let you see, but the ones his fun stories about sad refugees tell you exist. That it could heal your own wounds, so small, so faraway in comparison. Or worse, that he will think you are appropriating what you’re not entitled to, as if you are putting your hands under the skin of history, pressing on a bruise that isn’t yours to feel.

What he really wanted—back then, now, both—was to be a comic book hero. You think about the ways to tell him he kind of already is.

Here is one way.

Tell him about the night the lonely girl, now a grown woman, hears the story of the comics in the septic tank for the first time. How she goes to sleep restless. How it feels as though her heart has been cut out, but in the morning she will wake to find it full and the restlessness renewed. Tell him how at first she thinks it’s a kind of melancholia, but it’s stranger and stronger than that. It is a teenage girl’s breathless admiration for a teenage boy’s bravado, combined with a mother’s fear that any terrible thing that has ever happened to a child will now or in the future happen to her child. It is the concrete distillation of an abstract truth; that all the world’s dark ugliness has never yet been able to extinguish that thing Nadine Gordimer calls the firefly flash of real life.

Tell him how that night the girl checked in on her son, as she does every night. How she saw in sleep little visible sign of the man he was slowly becoming. How it was hard not to compare him to the boy in the attic room in Bosnia, dreaming about his comics as they drifted through raw sewage in their dark, plastic wombs. A little older than her son is now, true, but still a boy, just, whatever he’d probably say.

Don’t tell him how she would cry for those shitty comic books she can’t smell, because he wasn’t crying over them and they were his comics. Explain instead that you will not forget this story of how once, two boys in Banja Luka did something brave and stupid and kind of miraculous. That miracles aren’t always obvious. That miracles happen when someone is closing a window, or walking dully along. When it comes to it, really all you have to give is a story of a bungled comic book rescue, not the object restored. And it is a very small thing. Give it anyway. You may as well.

Liskeard, Cornwall