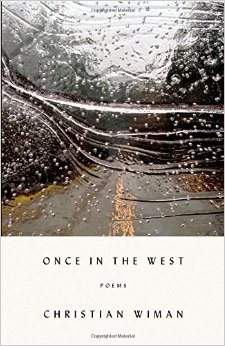

Once in the West by Christian Wiman

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2014. ISBN 9780374227012

Intensity, eye-searing intensity, characterizes this book from first to last page. The poems are divided into three parts, titled respectively “Sungone Noon,” “My Stop Is Grand,” and “More Like the Stars.” These titles are exactly apt given that the poems in the first part are characterized by memories of harsh life rendered in imagery as vivid and unflinching as the light of “high noon,” given that the poems in the second part are mostly driven by struggle with terminal illness so “my stop” can be read as a stop on “the El” (which appears in two poems as a central metaphor) and as “my final stop,” and given that the final section directly confronts eternity in an end-stop present. The sequential arc of the poems is one of the best I’ve seen in years.

Intensity, eye-searing intensity, characterizes this book from first to last page. The poems are divided into three parts, titled respectively “Sungone Noon,” “My Stop Is Grand,” and “More Like the Stars.” These titles are exactly apt given that the poems in the first part are characterized by memories of harsh life rendered in imagery as vivid and unflinching as the light of “high noon,” given that the poems in the second part are mostly driven by struggle with terminal illness so “my stop” can be read as a stop on “the El” (which appears in two poems as a central metaphor) and as “my final stop,” and given that the final section directly confronts eternity in an end-stop present. The sequential arc of the poems is one of the best I’ve seen in years.

The trinity of parts is preceded first by a prayer that the anxious and despairing reader “might find / here / a trace / of peace.” Peace, even a trace of it, is hard to find in the harsh/coarse reality of part 1, but here and there “a few flowers / flower / out of all this shit.” In this section, we encounter a poetic technique that is used throughout the book. Wiman creates an urgent, gritting tension, not just through his subject matter but more so by his use of very short lines (often two or three words), which are strongly iambic and loaded with frequent but unpredictable rhyming. The effect is various, depending on the poem. In some cases, it creates a brutally succinct expression that matches the realities described; in other cases, the lines seem to lurch forward in a kind of desperate delirium of sonic tautology. The elderly in a rest home are “squeegeed people” in a dining-hall line, “crushed- / cricket / twitches / of existence / testifying / less to survival / than simply / to less.” In “Big Country,” we read “One answer’s / cancer / on a slow boil / in the bones / of a woman / who sleeps / five feet / from the wide-screen / rape-screams / of a woman / her granddaughter, / motherless, / fourteen, / mainlines . . . // Enter the pug. / It sniffs / the rinsed / vomit tub . . .”

How grateful the reader is, then, to encounter the opening lines of “Memory’s Mercies” not quite halfway through the book: “Memory’s mercies / mostly aren’t // but there were / I swear / days / veined with grace.”

The second half of the book is dominated by spiritual and religious struggle, desperation, anger, acceptance, insight, bitterness, love, confession, witness, and many more things, a complex and deeply moving collection of poems that must be read rather than described. Christian Wiman is a Christian who in fact believes, but who also argues with his belief and God himself. This last feature is an accepted practice in the Jewish tradition, and it adds a poignancy, authenticity, and deep humanity to these wrought utterances. It’s fitting to end with one fleeting vision of riding the El in the dark to work, “stapled to people, sweating hate,” where the speaker once “saw a grace of sparks / struck from the tracks / blast every residual individual dark / from every face turned to see it / vanish instantly into the air, / so fair it touched the roar with silence” (the last line quoting Edward Thomas).

Fred Dings

University of South Carolina