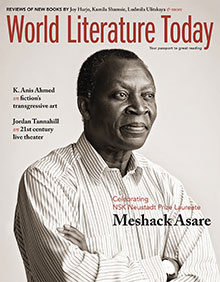

Growing Culture as Essential Knowledge: The 2015 NSK Neustadt Prize Lecture

Speaking before a packed audience at the University of Oklahoma last October, Asare reflected on culture as our “mandate to live life and express with freedom our being here in the world as human beings.”

In a world that turns and rolls along on lofty impressions of itself, it takes a truly special person to step out of the halo and bustle of adult sophistication even for a moment and look for conversation inside the unaccomplished world of the child. But some persons do—persons who are commonly known as parents. Out of responsibility and sentiment, mothers and fathers are often drawn into a child’s still-emerging world. I believe that is what we, too, are doing now, drawn by responsibility and sentiment to celebrate excellence in children’s and young persons’ literature, though not all of us here may be parents in the ordinary sense. But as Friedrich Schiller explains, “It is not flesh and blood but heart that makes us fathers and sons.”

That is plain passion, and the Akan people of Ghana, too, suggest similarly that such is the character of a person—female or male—that deserves the appellation Obaatan. Yet this is not an appellation that they bestow on just any parent, for it also expresses appreciation, reverence, and adoration of divine care and sustenance for everything that exists and lives—and one often hears the laudatory utterance in moments of serendipity, “Onyame baatan pa,” God the good parent. Thus, besides supporting the attribution of the parental tendency and expression to passion rather than filial bond, traditional Akan perspective adds a somewhat ethereal dimension. Bearing this in mind, one may perhaps suggest that whatever it is that moves an adult person to give dedicated attention to the interests of a child must be of extraordinary nature.

To begin with, the person may be one of uncommon sensitivity and perception and therefore hold the conviction that a child contains everything that is the sum of humanity, and then more—that a child also carries potentiality, for whatever the human race is going to become in the future is already contained in a child. Furthermore, this person, this parent Obaatan, is ever aware that in the end, we become only the adults that our childhood lives and experiences prepared us to become.

Perhaps at this point we may even cite a rather unlikely similarity here: a farmer’s “religious” dedication to the initial tasks of preparing the soil, nurturing it with necessary enrichment, and sowing the seeds, though by custom, a farmer’s recognition is determined by the volume of harvest. Here, I think, the parent, Obaatan, and the farmer converge on the commitment to the beginnings and nurturing of life. This may explain why Ghana seems to achieve more success in the field of literature for children and young persons in Africa, for they say in Ghana, “If the yam is bad, blame the soil in which it grew. Don’t blame the yam.”

The farmer is committed to processes of farming from the beginning to ensure the best possible start in life for the seedlings and does not skimp on dedication to them. And there is another thing—the sameness of “farming” and “culture.” Basically a farmer listens seriously to the earth, for the earth talks and the farmer must know what it says. How else will the seedlings be sown and nourished in the right soil, shielded from storms, appropriately supported and protected against blight in the air? It all amounts to “culture,” and the significance is the same. No matter what others may think, to this person, the parent, Obaatan, culture is essential knowledge, the mandate to live life and express with freedom our being here in the world in ways that are recognized as human and valued by the community of human beings.

This person who bends to the world of the child, this parent, Obaatan, farmer, is a keen observer, believes that the process of evolution continues just as the world continues to reveal its nature to us. So, avoiding the idea of “faith” for reasons obvious and obscure, though this person might still hang onto its shadow, this person dwells positively on belief, potentiality, and expectation. Finally, this person seriously believes that by every thoughtful word that is formed in the broad diversity of literature, the world defines its wholeness and reveals more comprehensively its richly layered sameness. This is the true image of this parent, Obaatan, farmer person.

October 23, 2015

Norman, Oklahoma