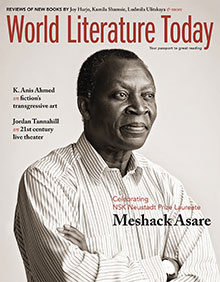

Meshack Asare in the Pantheon of Ananse

Parkes read the following tribute at the banquet honoring Meshack Asare as the 2015 NSK Prize winner.

Meshack Asare, winner of the NSK Neustadt Prize for Children’s Literature and Ghana’s leading children’s author, has published several books, and yet when I nominated him for the prize and had to choose a representative text, I had no hesitation in choosing The Brassman’s Secret. I can’t say at what point The Brassman’s Secret became one of those books for me, one that leaves an imprint on the psyche. All I know is that for years—in fact, for the past thirty-two years—I have been recommending it to anyone who will listen.

Perhaps my initial connection with the book was because, on the surface, it spoke of things that I recognized; things like Adinkra cloth and the pounding of fufu. But considering that there are several books from Ghana that I read that had the same engine of familiarity, there had to be something else that kept The Brassman’s Secret plastered to the tip of my tongue.

by Meshack Asare

In time, I’ve come to realize that the persistence of its spell is because Meshack does the simple things well—the language is clear, the plot is compelling, the characters are at ease in their skins. The Ananse tales of the Asante, whose characters form the pantheon of traditional stories, have endured for these same reasons: with a backbone of clear language entwined with compelling plot, they have traveled across oceans, surviving changes in the names and traits of their characters. In the Curaçao, Aso Yaa becomes Shi Maria; in the southern United States, Ananse becomes Aunt Nancy, and some of his famous exploits are also attributed to Brer Rabbit.

If the change in identity and characteristics seems puzzling at first, it is absolutely logical if you consider the notion of characters being at ease in their skins. Essentially, as populations move and change, the nature of the people alters, and what they are at ease with transforms with it. This is why Ananse stories have such a strong power of endurance, because they allow for that. Actually, the manner in which they are told plays to that—every family tells the story in their home; the home becomes the place, the heaven the characters play in, the gods are the children listening. There is no better way of creating engagement, of fomenting timelessness.

The form of the creatures that carry breath within the landscape of the story, and the landscape itself, may change, but the moral—the nucleus of the story’s music, its tonal center—remains the same.

In a world as fast-moving as ours is, the endurance of tales such as the Asante peoples’ Ananse stories—carriers of history and teaching—and of Meshack Asare’s The Brassman’s Secret is remarkable. So what is the secret? Loath as I am to overtheorize storytelling, something I consider to have a spiritual underpinning, I find that stories that surf through the rough seas of time, keeping their balance regardless of the waves of distraction each era throws at the human imagination, have, along with their flexibility, a kind of precision of purpose that serves as their anchor. The form of the creatures that carry breath within the landscape of the story, and the landscape itself, may change, but the moral—the nucleus of the story’s music, its tonal center—remains the same. There is a poetry in that precision that gently shackles the heart, refusing to be separated from the listener, the reader, from the memory.

It is vital not to forget that Meshack Asare is a writer as well as an illustrator, so his excellence does not simply involve the mastery of one kind of precision, but two. I remember, as a boy of thirteen, happening upon a large-format book in our school library that was on the work of the Swiss-Italian sculptor Alberto Giacometti. For weeks after that I bored my friends with the anecdote of how Alberto’s younger brother, Diego, sometimes had to intervene to stop the artist from carving his own famously thin figures out of existence. I was fascinated by that anecdote because it spoke of fine margins, the delicate balance between an acclaimed piece of art and unsalable bits of metal. Those are the kinds of margins that any great work of art has to navigate; therein lies the poetry of precision.

This brings me to my choice of The Brassman’s Secret as the representative text when I nominated Meshack Asare for the NSK Prize. Meshack Asare is a fantastic writer and has produced several memorable books, including prizewinning titles such as Tawia Goes to Sea (1970), which received the unesco citation “Best Picture Book from Africa,” and Sosu’s Call, which won the 1999 unesco First Prize for Children’s and Young People’s Literature in the Service of Tolerance. All of his work has a respect for history and an element of teaching. To my mind, however, The Brassman’s Secret is the title in which his dual skills are perfectly in sync.

Yes, it spoke of familiar things, but it dragged us into the underpinnings of those things, elements we had never explored, the rich history underlying traditions we took for granted. It was especially pronounced for us urban dwellers. That the book covered so much, yet was not bogged down in detail, remaining limpid and exciting, owed much to Asare’s skill as an illustrator and a pinpoint clarity of purpose, a retention of the moral-driven approach of the traditional Ananse tale. Holding it all together is a masterful plot that encapsulates elements of the detective and thriller genres. I consider it one of the high points of his career.

Meshack Asare was born in 1945 in the central region of Ghana, where a language very similar to Asante Twi (the language of the protagonist in The Brassman’s Secret) is spoken, and is of the transition generation of Ghanaians who were born in what was known as the Gold Coast and witnessed the coming of independence and the naming of Ghana. Significant in that generation was their early link to traditional life and later separation from home for Western-style education in boarding schools, making Asare an ideal conveyor of traditional knowledge to our generation. I think that this authentic connection to the traditional is part of what deepens the appeal of The Brassman’s Secret. It is a story that outlines a day in the life of a rural boy whose father makes gold weights—the prose is concise and accessible, lending a quiet dignity to the rural lives it describes. There is no question that the characters we encounter lead full, content lives.

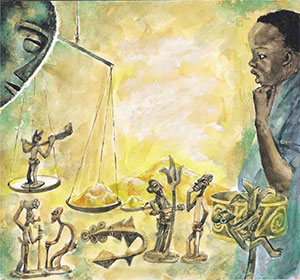

In a society—indeed, an entire continent—in which, as a result of the colonial encounter, the educated and the urban dwellers have come to regard their rural areas as impoverished and unworthy of attention, this in itself is revolutionary. It is a return to the milieu of the Ananse tales. Then comes the master stroke: Asare takes the reader (and his protagonist, Kwajo) into the secret world of the gold weights (stylized brass figurines used to weigh gold); in this new world, Kwajo—like Alice in Wonderland, like Hansel and Gretel, like Gulliver—must keep his wits about him as he undergoes a series of tests. This classic quest setup is perfectly complemented by monochrome pencil sketches that vary light and perspective impeccably.

As much as Asare’s illustration style was integral for the enjoyment of The Brassman’s Secret, it now appears that the style may have evolved from constraints—orange card was the only paper available to print on, there was a scarcity of watercolor paints leading Meshack to use india ink, and Educational Press (the original publisher) was unable to print in more than a single color. For me, however, the constraints only served to make the work stronger. The single-color illustrations create an atmosphere that doesn’t just read as a trip into the past; it feels like a trip into the past. The new edition of the title with color illustrations just does not feel the same, but thankfully the story remains as compelling as ever.

Meshack Asare is more than a mere writer and illustrator; a social anthropology scholar, he has a lifelong interest in history and social change. The themes of discovering the past and celebrating indigenous cultures and interests, which underpin his work, now feature heavily in my own work. His choice of characters from the humbler echelons of society help illuminate the world in new ways.

Meshack Asare is more than a son of Ghana. He, as with Ananse when he has outwitted the Sky God, has become a possessor and propagator of stories, retelling tales from other African countries such as Botswana, Zimbabwe, and South Africa. He is a storyteller of the African continent. His oeuvre has provided generations of children on the continent with intelligent, resonant stories that have entertained and enriched in equal measure. Meshack Asare is of the pantheon of Ananse—a writer and illustrator we should celebrate globally.

Norman, Oklahoma

October 23, 2015