Expanding the World of the Private Eye: Walter Mosley Becomes a Grand Master

Mexican crime novelist Paco Ignacio Taibo II frequently says that the North American crime novel is unthinkable in the context of Mexico, and his words are a reminder of how crime fiction, like all good fiction, is rooted in the cultural assumptions of a particular people and time.

Mystery writing arose out of Enlightenment rationalization and the principle of empirical observation (the scientific sensibility) contrasted against the gothic and Romantic faith in the reliability of sensation. Science, in these stories, was contrasted with intense feeling and conquered it with rational explanations. This could only happen in a culture engaged with these opposing theses, as we still are.

Along with this metaphysical conflict at the core of the mystery, many patriarchal and ethnocentric values were attached to the genre, as they were with other forms of entertainment. The great detective of early mysteries was often an odd person and occupied a place somewhere along a spectrum from passionate to passionless, but he imposed powerful skills of logic and observation to defend society against those who would undermine it. In the context of the time, for one example, the prejudice prevailed that women were not by nature as rational as men. Novels that resorted to women’s intuition or “playing a hunch” were regarded as cheating on the basic premises, ignoring the confirmable order of reality, never mind that the “logic” in many mysteries is ludicrous. Poe’s Chevalier Dupin, Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, and Leroux’s Joseph Rouletabille are the whitest of white men, and demonstrated along with many other fictional detectives a set of values that protect Western civilization against the evil schemes of the “yellow peril” and an assortment of swarthy villains.

Should we be shocked by the racial prejudice we see in Poe’s “The Gold Bug”? For us, it ruins a good kids’ adventure about lost treasure, but in that time? Though we now know such stereotyping generates a wrongheaded pattern of thinking that justifies discrimination and even violence, by their standards it was good-natured comedy. If African Americans appeared in mysteries, they were similar to the servant Jupiter in Poe’s story, usually decorative. That is to say, they were not there as simulations of real people. They were there for setting, novelty, or Stepin Fetchit–style comic relief. If the butler was a black man, he didn’t do the crime. He wouldn’t have any more logical motivation than the furniture in the conservatory. He may have witnessed something minor to report it, but as to having a relationship in the story to the other characters or the crime, not really.

It is only recently that African Americans consistently became more than one-dimensional characters in crime novels, and Mosley’s writing is often credited with changing this.

In 1918 the Ebony Company produced a one-reeler called A Black Sherlock Holmes, a broad parody for African American audiences with characters named Rheuma Tism, I. Wanta Sneeze, and Cheza Sneeze. As to the realistic portrayal of African American family, or community, there was little of that even in “race films,” movies made specifically for black audiences. The same complaint can be made about the other “outsider” identities in such movies and stories—inscrutable Asians and deceptive Arabs, or even Cockney gardeners. Exotic detectives had a vogue—Charlie Chan, Mr. Moto—but blacks were evidently not exotic enough to participate in this and were generally ignored. I once had the misfortune of being on a conference panel discussing “political correctness” and vividly remember a writer declaiming that she saw no reason to put Pakistanis and Vietnamese in books simply to be politically correct. To which I said, “No, you put them in the book because they are here. Leaving them out is lying.”

This is the importance of Walter Mosley, who was recently announced as the Mystery Writers of America’s newest Grand Master. It is only recently that African Americans consistently became more than one-dimensional characters in crime novels, and Mosley’s writing is often credited with changing this. Though he was preceded by any number of African American writers, they had a more limited impact. I suspect that the pulp era had a number of pseudonymous black authors tapping out a living at five cents a word, just as it had a number of women passing for hard-boiled male writers. The great Chester Himes began writing in the late 1930s after a term in the penitentiary. His first novel appeared in 1945, but in general, his work flew under the radar in the United States. It was first acclaimed in France, where he immigrated in the 1950s and achieved international success. In 1957 he wrote his first detective novel, beginning his Coffin Ed and Gravedigger Jones series, which managed to take advantage of the rise of pulp literature directed toward African Americans in the 1960s. The white-owned publishing company Holloway House published authors like Donald Goines (acclaimed on covers as “The Greatest Ghetto Writer That Ever Lived!”), Roland Jefferson, Robert Beck, and Joe Nazel, who could knock out a novel in six weeks. Yet rather like the blaxploitation films of that era, novels like these usually remained in the niche market. Finally, in 1988, Gar Anthony Haywood, one of the finest contemporary detective writers, managed with Fear of the Dark to poke a hole in the wall of the black detective’s “ghetto,” creating the entrance that allowed Walter Mosley’s Devil in a Blue Dress to become a best-seller and a modern classic.

As Mosley recounted it to the Daily Press (Newport News, Va.), he was thirty-four years old and bored with computer work at his job with Mobil Oil in Manhattan. No one else was around, so he wrote a sentence, “On hot sticky days in Southern Louisiana, the fire ants swarmed.” He had the thought “this could be a novel.” His storytelling impulse wouldn’t slow down once it was released. He writes every day, explaining that it is what he most enjoys in life. He has now authored some four dozen books. Mosley was born in Los Angeles, but his father was one of the many Louisiana blacks who sought opportunity by migrating. “These people,” he told the New York Times, “created an orally transmitted literary life out of a soil drenched by the blood of slaves and ex-slaves, Creoles, Cajuns, and the French.” In interviews he speaks of how the people who come from such a history can tell family stories of setbacks and suffering with a smile on their lips. Easy Rawlins, the Louisiana-born detective he created for Devil in a Blue Dress, is now one of the best-known fictional detectives in America, but Mosley does not limit himself to the Rawlins series. He has written a series featuring Leonid McGill (a contemporary private eye), another featuring Socrates Fortlow (an ex-con), and yet another featuring Fearless Jones. As inventive and improvisational as Miles Davis, he has also penned many “one-off” literary and science fiction novels, short stories, plays, screenplays, and nonfiction.

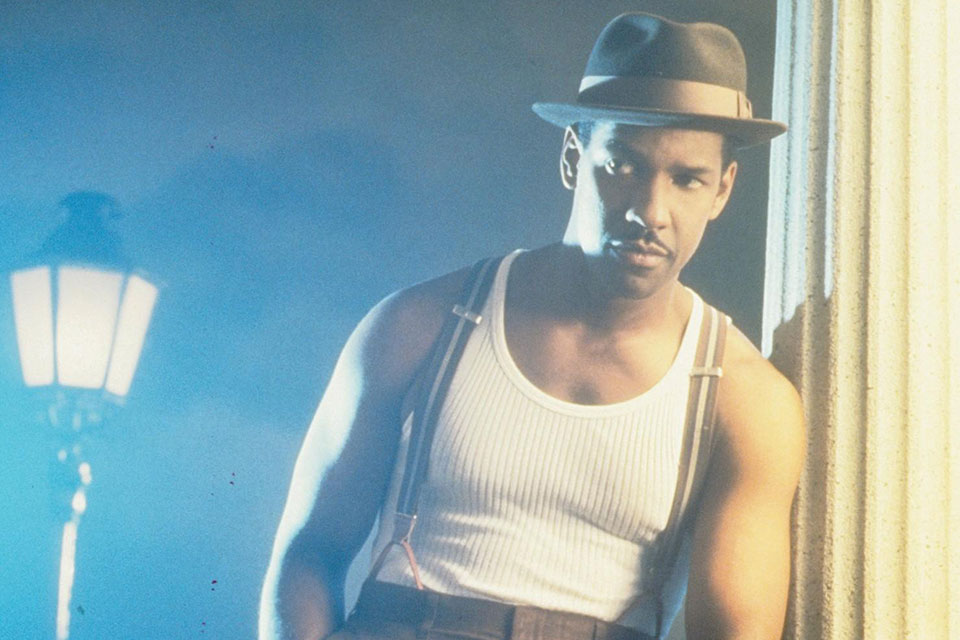

Devil in a Blue Dress is clearly based on the hard-boiled tradition: the tough detective in search of truth, the femme fatale, the mean streets, the cops who can’t be trusted. For fans of the pattern, this all has a comfortable familiarity that allows Mosley to bring in a further reality, confronting readers with the enormities of racism. The traditional crime novel is inconceivable in many black communities. Bad cops are not simply corrupt bullies, as they are in, say, Raymond Chandler’s or Dashiell Hammett’s novels. They are bullies because of what they perceive as their racial superiority. When private eye Philip Marlowe in Farewell, My Lovely goes into a part of the city transitioning into a black neighborhood, we get a shockingly realistic glimpse of the relationship between the cops and the residents. But only a glimpse. It isn’t central to the story. The racial aspect of the chapter has usually been written out of the film versions as unpalatable for white audiences.

The implicit social commentary that is so much a part of the hard-boiled novel allows Mosley to use the same framework to communicate racial realities.

The implicit social commentary that is so much a part of the hard-boiled novel, however, allows Mosley to use the same framework to communicate racial realities. One people’s justice is another’s barbarity. Perhaps by 1990 a large readership was ready for a more direct confrontation with the racial dynamics that corrupt so much of what happens in America. President Bill Clinton said Mosley was one of his favorite writers. The hardboiled detective novel, along with the police procedural, has always promised a more direct expression of the harsher realities, and though the preponderance of pulp jockeys merely exploited the sordid for shock value, a masterly writer like Mosley can adapt the tradition to his own significant purposes.

Since 1955, when the Grand Master award was first given to Agatha Christie, no African American has received it. Naturally much of the focus on Mosley will emphasize this, especially in a year when racial diversity was a controversy at the Oscars. Few people will be paying much attention to the fact that Mosley’s mother, born Ella Slatkin, was of eastern European descent, and Mosley embraces his Jewish heritage as completely as he embraces his African American heritage. His cousin taught him Yiddish curses. He learned to enjoy what he describes as the Jewish give-and-take of debating ideas from opposing points of view. He compares the experience of the Jews with that of African Americans and has provoked some anger by calling the Jews a nonwhite race, the “Negroes of Europe.” Yes, he says, Judaism is a religion, but most Jews are not particularly religious.

After reading The Color Purple, Mosley was impressed and took courses to develop his writing. One of his instructors, Edna O’Brien, told him, “Walter, you’re black, Jewish, with a poor upbringing. There are riches therein.” His books feature black hero protagonists because he feels they are highly underrepresented, but his Jewish background informs his portrayal of the black community and perhaps makes him even more insightful about it. Categorizing writers is something we often do, but it often is a fool’s exercise. What we really value in a writer is the uniqueness. Walter Mosley is Walter Mosley is Walter Mosley, and there are riches therein.

Palmyra, Virginia