The Books We Were

Certain cherished books are like old loves. We didn’t part on bad terms; but it’s complicated, and would require too much effort to resume relations.

If one’s first love is for Letters, people tend to come second (or possibly third). Yes, books are ink-and-paper relationships that can supplement and, at times, displace flesh-and-blood relations.

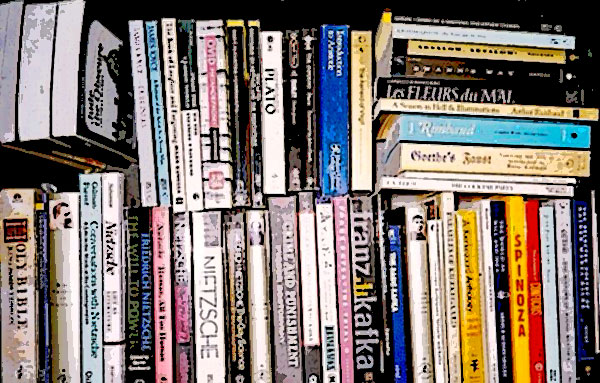

Such was my breathlessly intense, and evidently unhealthy, understanding of literature as an impressionable, voracious teenager. I read to get drunk and, to paraphrase Baudelaire, hoped to stay that way. A clutch of slim volumes altered my intellectual landscape and, at the risk of melodrama, saved my life. Past the intoxicating, escapist, aesthetic experience (style always mattered for me), these early loves knew me before I knew myself and confessed my secrets—speaking the yearnings of my still-inchoate soul far more eloquently than I could ever dream at that tender age. Sensing my desperation and need, I believed these books opened themselves up to me so that they were a more real and alive world than any other I inhabited.

The first, which made me suspect I might (want to) be a writer was Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray. Its relentless cleverness made for a heady ride, and I might have underlined every other line while highlighting the rest. By donning a mask of brilliant wit, Wilde seemed to have split himself in two and outdistanced his pain. This was a trick worth learning, my sixteen-year-old self intuited wordlessly, as was his apparently effortless knack for pithy summary. “I summed up all things in a phrase, all existence in an epigram: whatever I touched I made beautiful,” Wilde would go on to say in “De Profundis” (which I devoured shortly afterward, along with all his immodest utterances, in various genres). Yet, fond as I am of this early crush, I cannot bear to return to Wilde’s Gray. Past his glittering style, I find the cynicism suffocating. As Franz Kafka is supposed to have said to Gustav Janouch of Wilde’s work: “It sparkles and seduces, as only a poison can. . . . It is dangerous, because it plays with truth. A game with truth is always a game with life.” Then, there was Kafka, and his sublime self-loathing and life-recoil. He also came to me in my teens, when I was particularly susceptible to that volatile cocktail. Those hallucinatory short stories, especially his “A Hunger Artist,” hit me like a dark epiphany: “I have to fast, I can’t help it. It is just that I couldn’t find the food I liked. If I had found it, I would have stuffed myself like you or anyone else.” Then came the exquisite masochism of his diaries, which I inhaled like a guilty pleasure, and concluded with his choice aphorisms. Of all his work, actually, it is the aphorisms that I can return to, which are, somehow, greater than the sum of the man and his torment.

Nietzsche’s Zarathustra combined everything I needed to hear at the time: rebellious philosophy, stylish nihilism, vicious humor, and something akin to prophecy.

Before I turned twenty, I was to encounter the love of my life—the one that would set my world spinning and take me nearly two decades to recover from: Nietzsche. His Zarathustra combined everything I needed to hear at the time: rebellious philosophy, stylish nihilism, vicious humor, and something akin to prophecy. He spoke the soul-splitting contradictions I hardly had words for—“Body and soul, I am more of a battlefield than a human being”—and, in my intemperate enthusiasm, I can say that, for the next decade or so, he was nearer and dearer to me than any living soul. Incredible, now, to think it.

Nietzsche handed me over to that other hysterical prophet: Dostoevsky. And, if memory swerves correctly, I was so caught up in his Notes from Underground that I hardly noticed that the train I was on had derailed. When I did (because everyone else was panicking and scrambling to get off the tram), I proceeded to disembark, in measured pace, without tearing my eyes off his delirious pages. And so it was: one Existentialist horror writer after another kicked me around for a bit then passed me, the besotted lover, off to their buddies to have some violent fun with.

Which is why when, belatedly, I recovered my senses and bearing, I had to set these seductive invalids aside for some time. For, just as they’d oxygenated my days, they’d also left me in a moral, spiritual daze. I felt I’d just barely managed to escape their clutches and could not afford to flirt with their frailties any longer—from fear I might be dragged to that treacherous space where they initially found me. They began to all seem like otherworldly, gilled creatures thrown upon the earth, gasping for a breath from their home atmosphere. I just couldn’t bear to pity any more suffering—each one, forever, on the verge of nervous collapse. I’d combed their letters, I’d inhabited their journals, I’d read between their lines. Quite simply, I had to keep these once too-dear books at a distance, as I was afraid of what echoing responses they might draw from me.

Quite simply, I had to keep these once too-dear books at a distance, as I was afraid of what echoing responses they might draw from me.

Only a few years ago was I able to formally say good-bye to these formative influences in a book of conversations: The Artist as Mystic. In this love letter to my early masters (including Kierkegaard, Rimbaud, Baudelaire, and the usual suspects), I was finally able to see, with the 20/20 vision of hindsight, that what I was attracted to in these dark thinkers was an anguished yearning, a longing to utter what’s ineffable: in short, the Light. It’s just that with my night vision, I could only take so much glare, and could not find my sustenance in sunlit spaces . . . yet.

“At the end of my suffering / there was a door,” writes Louise Glück in “The Wild Iris.” That door would lead me to poetry that was at the threshold of revelation. The sort of poetry that had set me alight in Eliot’s Four Quartets and Rilke’s Duino Elegies (two loves from my past that I can and do return to). And, past poetry, further along on the other side of that door, I made a somewhat destabilizing, liberating discovery: I found that not only did I care far less for the tyranny of the mind and its chew toys, which I previously cherished, but “literature” also seemed to matter much less.

To quote Rumi, who spoke of the limitations of poetry when he had become a celebrated poet: “What, after all, is my concern with Poetry? In comparison with the true reality, I have no time for poetry. It is the only nutrition that my visitors can accept, so like a good host I provide it.”

And, just like that, my early love for Western philosophical literature slowly came to be replaced by Eastern mysticism. First, through that little inexhaustible marvel of a book, the Tao te Ching, bursting with fruitful paradoxes and then, in quick succession, mystics of all stripes (Buddhist, Christian, Sufi). Maybe this sounds odd, but through the eyes of love (quietly gazing past the loud surface differences), I find that I can see the luminous spirit of Rumi in Nietzsche, only stunted. I recognize that I am drawn to the captivating contradictions in both, the serious play and their radical ecstasy. But I see the example of scholar-become-poet, who then goes on to make of his entire life a work of art, more beautifully and spiritually realized in the Persian master.

And, just like that, my early love for Western philosophical literature slowly came to be replaced by Eastern mysticism. First, through that little inexhaustible marvel of a book, the Tao te Ching, bursting with fruitful paradoxes and then, in quick succession, mystics of all stripes (Buddhist, Christian, Sufi). Maybe this sounds odd, but through the eyes of love (quietly gazing past the loud surface differences), I find that I can see the luminous spirit of Rumi in Nietzsche, only stunted. I recognize that I am drawn to the captivating contradictions in both, the serious play and their radical ecstasy. But I see the example of scholar-become-poet, who then goes on to make of his entire life a work of art, more beautifully and spiritually realized in the Persian master.

“What you are seeking is also seeking you,” Rumi says. Certain cherished books, like old loves, find and transform us at decisive stages of our lives. Thus, they remain emblazoned on our minds and hearts, whether we like it or not. And when we must address these emissaries of the past (as I find that I am doing now), we should try to speak of them with the respect and tenderness befitting a ghostly self. If I might be permitted one parting quote from another Sufi mystic, Al-Ghazali, “Only that which cannot be lost in a shipwreck is yours.” The rest is flotsam.

Editorial note: Yahia adds that the Smiths were “almost exclusively responsible for the ‘soundtrack’ of my restless young adulthood. As you will see, Morrissey’s lyrics to ‘Rubber Ring’ basically sum up my essay.”