Malaysian English Writing Today

Although the world has opened up for Malaysian glocal writers in the past fifteen years, they still face the demon of self-censorship. Dipika Mukherjee considers the recent zeitgeist in Malaysian writing and just exactly what has changed—and hasn’t.

In 2002 Kirpal Singh, Mohammad Quayum, and I co-edited The Merlion and the Hibiscus: Contemporary Short Stories from Singapore and Malaysia, an anthology published by Penguin. This book was explicitly designed to present Malaysian and Singapore voices to an international audience and was largely a labour of love; books of short stories don’t sell, and fifteen years ago, before names like Lahiri and Munro won prizes like the Pulitzer and Nobel, anthologies were a hard sell indeed. Plus we were trying to publish short stories from a region where writers writing in English were highly suspect as postcolonial pretenders with colonialist souls.

Few writers from Southeast Asia reached an international audience then, but this book, because of the marketing arm of Penguin, was reviewed in publications from Hong Kong to India. Whereas Malaysian and Singaporean newspapers treated the project with nationalistic fervour and announced Literary voices for export and (perplexingly) Yes, Size Does Matter, a reviewer from India pointed to a certain thematic bravery:

Is “multiculturalism” really as disinterested and neutral as it seems to be, or does it have its own silences, its own propensity to become part of certain hegemonies? These are questions that must be asked. (The Statesman, April 21, 2002)

As editors, our biggest slap on the wrist came from a reviewer in Hong Kong, who wrote:

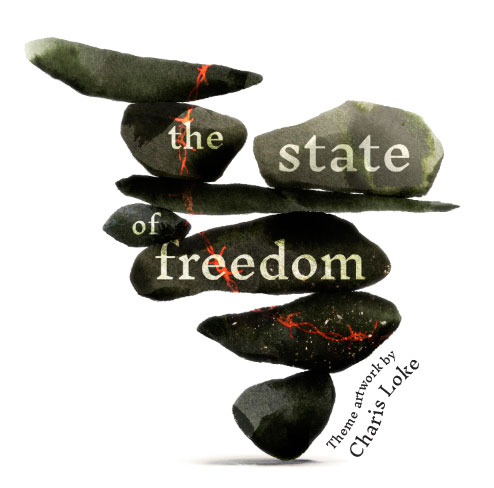

Absent for the most part are the heavy political themes of freedom and religious tolerance that often dominate coffee shop conversations. (Far Eastern Economic Review, July 4, 2002)

Wonderful. So we had produced a timid and polite little collection that had little sound and even less fury. The stories were well crafted and written by the leading lights of the region in 2002, but unlike the South American writers who were mining gold with magic realism retelling stories about sociocultural upheavals in their countries, our anthology largely left taboo topics alone.

In 2018 I co-edited my fifth anthology of Malaysian English writing, Endings and Beginnings, with Sharon Bakar. This anthology grew out of prizewinning and publishable entries from the D. K. Dutt Award for Literary Excellence, which was established in 2015 as an annual contest to foster new Malaysian voices.

From 2002 to the latest anthology in 2018, one would expect changes; but has anything really changed in the zeitgeist of Malaysian English writing in a decade and a half?

In 2019 self-censorship continues to foster a certain timidity in regional writing. Of course, the self-censorship is not without cause; The Merlion and the Hibiscus was held up in customs in Johor Bahru for a week as the officers decided whether the homosexual story in this volume was “safe” for Malaysian consumption. During the editing of The Merlion and the Hibiscus, a young man in his early twenties withdrew a story about wrestling with sexual identity from this collection. “I’m Malay, lah,” he said, by way of explanation. “They’ll think the whole community is like that only.”

Unfortunately, identity politics, and how writers choose to write about fluid sexual identities, still plagues Malaysian writing.

Unfortunately, identity politics, and how writers choose to write about fluid sexual identities, still plagues Malaysian writing. While bemoaning the state of literature in the region and the paucity of good writers, there is still a numbing self-censorship that makes authors draw back from the precipice before they get too near. To be a writer in Malaysia while steering clear of politics and ideology, religion and language, one is reminded of Jane Austen’s “the little bit (two Inches wide) of Ivory on which I work with so fine a Brush, as produces little effect after much labour.”

When I published my debut novel, I too tussled with the demons of self-censorship (Will it be banned? Do I have the authority to write this book?). A book on the sociopolitical realities of Malaysia, this novel opened with a model being blown to shreds in a field in Shah Alam. I continue to get questions about the imaginative leaps in this work, for this story is rooted in toyols and bolster ghosts as well as the Brahma-Saraswati lore, brought to life by snippets from news reports. I continue to explain—to largely Western audiences—that I simply dived into the cornucopia of local fables, and there is an abundance still untapped in Malaysia.

While bemoaning the state of literature in the region and the paucity of good writers, there is still a numbing self-censorship that makes authors draw back from the precipice before they get too near.

Ever since Vikram Chandra wrote a seminal article about “The Cult of Authenticity” in 2000, writers have been wary of peddling a country’s exoticism—the perils of peddling one’s ethnicity, really—as a widely successful multigenerational migrant saga that sells so well in English-speaking markets but says nothing to the region it sprouts from. Fixi, a leading Malaysian indie publisher, wittily warned against irrelevance in a manifesto to all new writers seeking publication under their imprint: We publish stories about the urban reality of Malaysia. If you want to share your grandmother’s World War II stories, send ’em elsewhere and you might even win the Booker Prize.

In the past fifteen years, the world has opened up for Malaysian glocal writers, those writing globally while rooted firmly to local sensibilities. Some remain resident in Malaysia: writers like Hanna Alkaf, who in 2019 takes on mental illness and May 13th in one breathtaking Malaysian YA novel; Brian Gomez, who can write A Devil’s Place as a brilliant urban Kuala Lumpur noir; Preeta Samarasan and Bernice Chauly and Beth Yahp rewriting the family saga as domestic and sociopolitical unrest; Zen Cho playing with dystopian worlds with Malaysian flavours; and Yangsze Choo taking The Ghost Bride to Netflix fame, right on the heels of the phenomenal Hollywood success of Crazy Rich Asians.

Stories coming out of Malaysia take more chances now.

At the George Town Literary Festival in November 2018, Malaysian writers addressed sexuality and politics through inspirational poetry jams and midnight live storytelling sessions that frizzled with promise and engagement. Stories coming out of Malaysia take more chances now. Writing the Malaysian migrant story has moved on to writers like Raidah Shah Idil and Marc de Faoite, rooted in Malaysia but circumnavigating the globe for a place in the world to forge relationships familial and communal, whether in Malaysia or Ireland or Australia. Sharmilla Ganesan rewrites Southeast Asian myths and fables with gorgeous resonance, and Sumitra Selvaraj and Saras Manickam are writers to watch. Manickam's short story is shortlisted for the Commonwealth short story Prize along with Lokman Hakim's short story translated from Malay to English by Adriana Nordin.

At the George Town Literary Festival in November 2018, Malaysian writers addressed sexuality and politics through inspirational poetry jams and midnight live storytelling sessions that frizzled with promise and engagement. Stories coming out of Malaysia take more chances now. Writing the Malaysian migrant story has moved on to writers like Raidah Shah Idil and Marc de Faoite, rooted in Malaysia but circumnavigating the globe for a place in the world to forge relationships familial and communal, whether in Malaysia or Ireland or Australia. Sharmilla Ganesan rewrites Southeast Asian myths and fables with gorgeous resonance, and Sumitra Selvaraj and Saras Manickam are writers to watch. Manickam's short story is shortlisted for the Commonwealth short story Prize along with Lokman Hakim's short story translated from Malay to English by Adriana Nordin.

I will close with a quote from Rehman Rashid, a friend and colleague who wrote in 1993:

. . . Malaysia was a hopeless mess of conflicting priorities, mutually unintelligible languages, contradictory cultures and blinkered religions. Malaysia’s politics were divisive, its economy exploitative, its pillars of authority buttressed by an impenetrable scaffolding of draconian laws upheld by a parliament in which dominance seemed to matter far more than debate. There was no reason for Malaysia to have survived this far. . . . But Malaysia had.

And Malaysian writers will too—as long as they continue to confront and challenge the gritty realities of Malaysia. They will not only survive but prosper. There is a wealth of talented writers in this region who are just beginning to find their global—intrepid—voices.

Chicago

An earlier version of this essay was published in The Edge, Malaysia, on March 4, 2019.