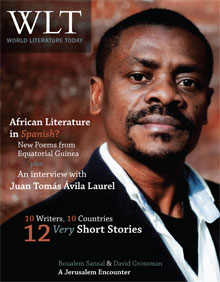

“A Rustle in History”: Conversations with Boualem Sansal

“I make literature, not war. . . . Literature is not Jewish, Arab, or American. It tells stories to everyone.” These are the words of Boualem Sansal, an exceptionally brave and talented Algerian writer and recipient of several literary awards in France and Europe, in response to the numerous and violent reactions from his fellow citizens and Muslims around the world when he participated in the 2008 Salon du Livre (the annual book exhibition) in Paris. Arab countries unanimously boycotted the event because the honored country was Israel. Sansal, a writer preoccupied with peace, justice, and dialogue, has been one of the most vocal opponents to his country’s dictatorial governments since Algeria’s independence (1962) and to the Islamist ideology that spawned the horrific crimes committed in its name during the decade-long Algerian civil war (1990–2000). He lost his high position in the civil service because of his writings in 2003, and his books have been banned in his country since the publication in 2006 of his essay Alger: Poste restante, Lettre à mes amis Algériens. At the 2008 Salon, Sansal had been invited to present his latest novel, Le village de l’Allemand, ou le journal des frères Schiller (2008; Eng. The German Mudjahid, 2009), also banned in his own country.

Le village de l’Allemand tells about the painful discovery made by Rachel (short for Rachid Helmut), an Algerian man living in France, of his father’s past as a former member of the SS. He stumbled upon his German military notebook after the Islamists had assassinated his parents with dozens of other villagers during the Algerian civil war. In the wake of his discovery, he begins to research the history of the Holocaust (which Sansal names the Shoah, to be more accurate) and even travels to the places and concentration camps to which his father had been assigned. Finally, taking moral responsibility for his father’s sins, he commits suicide. His younger brother, Malrich (short for Malik Ulrich), also travels to the village, finds and reads his diary, and writes his own. Through Rachel’s pages he discovers truths that “should be told to the children,” as quoted from Primo Levi’s poem If This Is a Man. Malrich eventually makes a life-changing decision, summoning the courage to confront the imams that reign over his cité de banlieue (the ghettoized projects in a Parisian suburb) “like Nazis in a concentration camp.” Sansal received countless threats against his life as a result, but they have still not prevented him from living in his country. To him, it is the most efficient manner to go on speaking “truths not to be told” to his fellow citizens.

A few years, books, and truths later, Boualem Sansal continues to find himself surrounded by controversy, as with his most recent novel, Rue Darwin (2011). It was awarded the 2012 Prix du Roman Arabe,[1] but before Sansal was to receive the prize on June 6, 2012, he dared travel to Israel to participate in the International Writers’ Festival in Jerusalem, May 17–20. He had been invited there as a guest of honor. Hamas issued threats and denounced him as “a traitor to his Palestinian brothers.” The pressure from the Arab governments that sponsored the prize caused the Arab Ambassadors’ Council to decide not to give him the award. Because of the uproar in France among intellectuals and the media, Sansal was a few days later awarded the prize by the jury that had chosen him, but denied the money that should have come with it.[2] His response to Hamas and all the critics about his trip was immediate: a letter full of verve and humor published on May 24, 2012, on the French Huffington Post, entitled “Je suis allé à Jérusalem, et j’en suis revenu riche et heureux” (I went to Jerusalem, and I returned delighted and enriched; WLT, September 2012, 16–19). Again Sansal showed his commanding courage and derisive humor against the political intrusion of Hamas and the Arab states into his art and his freedom. He also renewed his plea for peace between the only legitimate peoples who could achieve it: the Palestinians and the Israelis.

When I met Boualem Sansal for the first time, in Lyon, France, at the 2010 Assises Internationales du Roman, his novel The German Mudjahid had already been translated into several languages and had received prestigious literary prizes in France (2008 RTL Grand Prize and SGDL Grand Prize for Literature).[3] Since then it has received more awards like the Prix de la Paix des Libraires Allemands (German Booksellers’ Peace Prize) in 2011, and more are expected around the world as the novel is being translated into more languages. In his panel at AIR, organized around successful novels written in the form of diaries, one of the writers expressed her surprise (felt by many of his readers) that he, a Muslim living in an anti-Semitic country, should write about the Shoah and express such compassion. My interview with him was wonderful, even though the tape recorder I bought for the occasion failed to work and I had to write all his answers at record speed. Those notes were then lost in boxes of books and documents that I shipped from Europe, and were only miraculously recovered a few weeks ago. Added to the questions from the interview conducted on May 27, 2010, you will find a few more about his latest novel, Rue Darwin, which he answered on July 29, 2012.

Dinah Assouline Stillman: You are known for having a scientific background, and a few years ago you used to have a high position in government in the Ministry of Industry. How did the urge to write come to you?

Boualem Sansal: Because of my country’s woes: I found myself engulfed in war, violence, nonsense, and stupidity. . . . You think there must be something to understand, maybe there is a meaning behind all this. You try to sort out ideas, and writing is good for that purpose.

I did expect negative or outraged reactions, but I was far from imagining the death threats, and the most ridiculous accusations I have received: I was no less than “a hidden Jew,” “a Mossad agent” . . . The excessive violence and frothing at the mouth expressed by a few just took me by surprise: “This individual is attacking our most sacred things!”

DAS: Since you started writing with Le Serment des Barbares (1999), you have gained the reputation of a novelist of large and generous breadth, who does not recoil from criticizing what happens in your country. I would compare you to Émile Zola for the way you embark on long sentences to denounce false declarations or absurdities coming from the government or the Islamists. Don’t you like concision?

BS: I have been compared to Proust, never to Zola. You flatter me; I like both writers. Sometimes, one is very concise, but there are moments when profusion is more to the point. It is like love for a woman: sometimes one feels the need to express it over and over, and sometimes one does not. Also, when walking outdoors, one feels happy among nature’s luxuriance, while at other times it is the simplicity of Japanese gardens that moves you.

DAS: Why did you criticize not just the Islamists but also your government (with the consequence, as we know, that your books are banned in Algeria) when you “wrote letters” to your fellow citizens in Alger: Poste restante, Lettres à mes amis Algériens (Algiers: General delivery, letters to my Algerian friends)?

BS: Because it is the same, the Arab governments and the Islamists: to differentiate between Arab governments and Islamism is to not know the Arab governments.[4]

DAS: You are at the same time precise and profuse when you write about the FLN’s grip on Algeria since the country’s independence, the Islamists’ fanatics, and the quasi-absolute power of President Bouteflika. You compare them to pickpockets that have robbed the people. Why?

BS: They are petty thieves. They rob the people; they rob the nation’s riches. It is petty. They could develop their country.

DAS: What pains you the most in your country?

BS: As a society we do not do anything to change anything, but within the family or between friends, we rebuild the world every day. It requires some courage, and hard work, to make these changes, but we do not have that kind of courage.

DAS: What do you think could bring more hope to the Algerian youths whose main dream seems only to leave the country?

BS: For the moment, it is their only dream. They do not engage in their country’s future. However they are very ingenious at finding ways to leave the country. Either they embark on long years of studies that do not exist in Algeria, or they try to hoard as much money as they can to be able to leave the country. Our youths live in permanent frustration because of television, which shows them other horizons, other ways of living. It is terrible; they live in poverty and in constant sexual frustration because of our traditions.

If we were the same age, Albert Camus and I would have been friends; we would have gone to the same school since our two streets are very close. In the ‘70s, years after Algeria became independent in July 1962—I was then in my twenties—his novel L’étranger came into my hands and as soon as I read it, it was a revelation for me: Camus was evoking a world in which I had been living but which had utterly vanished.

DAS: In Alger: Poste restante, you are eloquent and often sardonic. I laughed at your long enumeration of French society’s “scourges”—about which every Frenchman keeps complaining and demonstrates his discontent in the streets—and at your advice to all French citizens to emigrate to Algeria, where nobody complains because no one dares to express ideas openly. You follow it by establishing an even longer list of the ailments that plague the Algerian people, notably the FLN regime’s lies about Algeria and Algerians, their historical past and having always had a single spoken Arabic (the majority of the population is Berber and speaks Berber dialects). Isn’t it understandable that your letter was deemed subversive according to your government? What were your fellow citizens’ reactions? Did they approve of you, support you, or vilify and threaten you?

BS: Both, but with a kind of ethnic separation: in Kabylia, the dominant Berber region, I am a hero. The Arabic-speaking people have disliked me for a long time, since the publication of Le Serment des Barbares (The barbarians’ oath), to be precise. So I convinced those who were already convinced. But a few other people reacted with genuine surprise: “We didn’t know!” For example, in Petit éloge de la mémoire, I gallop through three thousand years of Algeria’s past, which stunned the Algerians, who did not know their own history.

DAS: Not only have they not managed to silence you, but you did it again with your novel Le Village de l’Allemand. You wrote about subjects “not to be told,” like Algerian insurgents who received the help of former Nazi officers such as the two Schiller brothers’ father, for example, during the Franco-Algerian War. Above all, you broach the topic of the Shoah, not the most welcome in an Arab and Muslim country. Did you elicit any aggressive reactions?

BS: I did expect negative or outraged reactions, but I was far from imagining the death threats, and the most ridiculous accusations I have received: I was no less than “a hidden Jew,” “a Mossad agent” . . . The excessive violence and frothing at the mouth expressed by a few just took me by surprise: “This individual is attacking our most sacred things!” Everything is “sacred” in our country: the revolution is sacred, the Shoah is “a Zionist plot,” “it never happened.” To denounce anything is to “attack an entire nation.” But maybe in the not-too-distant future it will begin to be internalized and accepted, like the Vel’ d’Hiv roundup for the French nowadays.[5] It is important to know the truth. Admitting elevates the soul, doesn’t it?

DAS: When you went to the Salon du Livre in Paris in 2008, for which Israel was guest of honor, you stuck to your position, differing from the single-party position in your country. You angered your government and even intellectuals in the Muslim countries that boycotted the event. Weren’t you concerned not only about your books being forbidden but for yourself, like Salman Rushdie before, about having a fatwa issued against your life?

BS: Yes, certainly, and sometimes it can be physically painful, but what to do? I received threats, and also pleas, when they saw my determination to go: “Brother Sansal, we beseech you to change your mind.” The world is crazy! Israel is a country with legal standing; it does not make sense. I have, by the way, written an article that appeared in Le Figaro with the title “What are we boycotting in Paris?”

DAS: In spite of the great danger in which your books and your positions have put you, you still keep living in Algeria. Are there other courageous people like you in Algeria who search for truth and tolerance, for liberating words against the silence born of fear?

BS: Yes, there are many. Maïssa Bey is a good example among the novelists (see WLT, Nov. 2007, 27‑30). Among the young journalists, I admire Mustapha Benfodil, who has already written two novels.

DAS: And he is not threatened?

BS: Yes, of course, all the time, but it does not prevent him from going on. To me, what is disturbing is the number of Arab intellectuals who live in Europe and do not say anything against the Islamists. I would like to tell them: “Your opponents express their views everywhere, loud and clear, the Tarik Ramadans, the burqas [veils], the imams. Everything is here, in front of you, and you don’t do anything!” It is like refusing to assist people in danger. Although they were the first to criticize the institutions, they left the country furtively.

DAS: In your novel Le village de l’Allemand, you don’t merely reveal an unknown part of the Algerian civil war, you warn the French government about what is happening in the projects in the suburbs, which you compare to concentration camps because of the brutal influence of the Islamists on young Muslims looking for an identity. You even say of their organization they are like a state within the state. What is the real threat for France?

BS: It is exactly the same as the one that started in Algeria in the 1980s. It began with more people going to the mosque, more girls wearing the veil, and more beards being grown. . . . People thought it would pass, saying, “they are young. . . .” Then they started to be violent with young women, pouring acid on their faces, then killing people, and then what we all know, the civil war. It is exactly what is gradually happening now in France, and it should be stopped.

DAS: You remind me of the Algerian journalist and filmmaker Merzak Allouache. After he was threatened and had to leave in exile for Europe in 1993 to finish Bab el Oued City, his film depicting the rise of Islamist fundamentalism in Algeria, he said in warning: “What is happening now in Algeria will repeat itself in the future in the world and in Europe if people don’t pay attention to the phenomenon.”

BS: Yes, absolutely! But there are remarkable organizations in France that try to fight against anti-Semitism and communitarianism, for example Les Bâtisseuses de paix (Women Builders for Peace). It is an organization of Jewish and Muslim women who teach dialogue between the two religions and cultures through common activities. They try to prevent transferring the Middle East conflict onto France’s soil.

DAS: Tell me more about the names in your novel Le village de l’Allemand. Why did you choose the name Rachel for the eldest son who commits suicide after loading on himself the responsibility of his father’s sins? Is it a precise symbol?

BS: Yes, Rachel is a symbol. People should extricate themselves from anti-Semitism. They should feel a little Jewish.

DAS: Why?

BS: Because they are our history; they are the first of the monotheistic religions. They are the history of humanity, which is in permanent exile. I believe we have not yet finished with the Shoah and anti-Semitism. Since the Shoah, one still witnesses anti-Semitism, even though it is a phenomenon that should have been definitively uprooted. The Nuremberg Trials put a heavy cover on collective memory, which allowed people to forget about it and let the silence settle in. Unfortunately, from under the ashes, it is reviving: just look at its followers in France, in Poland, in a few Arab countries. So I could have given him any name, but I made up that name, and a few others. . . . Rachel is a very common name for girls in Algeria. One should transcend the divide between man and woman, sexism. It is good that it is at the same time a biblical and a Muslim name, because it achieves on most of the aims in my plot. As it is composed of Rachid, which means “courageous” or “wise” in Arabic, and of Helmut, a very Germanic name, its contraction as Rachel made my character appear to me quite differently, capable of an act so courageous as to research his father’s acts and take responsibility for them.

DAS: What about Malrich? Does the name Malrich have special meaning in Arabic or German?

BS: Malrich is poor. He lives in the projects in a suburb. He is young, he is seventeen, and has no job. The irony is that his Arabic name, Malik, means “king,” but with the caesura in the middle in both of his names, “Malik” and “Ulrich,” he becomes the opposite of rich in Malrich. At the time, I had spent entire weeks composing all these names, like El Deb, for the village’s name. Deb means “donkey,” a symbol for ignorance in my country. How could anyone want to stay ignorant? It is a mutilation. Man’s nature is to learn. How could anyone not search, find out, learn?

DAS: Amid all your social criticism in Poste restante: Alger, I am wondering why you do not spend much time on the condition of Algerian women since the Family Law in 1984, although they are the ones who have suffered more than men from Islamist fanaticism. Why?

BS: Because before Poste restante: Alger, I wrote Harraga, an entire novel on women. For me, Harraga is my best novel. The term means “to burn.” Undocumented immigrants are called “Harraga” because they burn their identity papers, so that they cannot be identified, and authorities cannot legislate against them. But for me, what is worse than physical exile is our women’s internal exile. They cannot even leave like the desperate Harragas, because they are locked indoors by their families at a young age, and when they are married later on, they are burdened with their own family responsibilities. And that is terrible! It is an absolute shame! I often tell my wife how badly I feel about it. I could be very violent to her or repudiate her in a wink. . . . And it is all legal and terrifying! And yet those who most defend this law are women, or I should rather say mothers. . . .

DAS: How can you bear to stay in Algeria, in spite of what you criticize in your country?

BS: If one can help advance matters, change things by fighting against inertia and fear, it is worth staying and fighting. I criticize President Bouteflika as one of the worst of our leaders, but I also criticize my fellow citizens too: you voted for him, now you have to suffer him!

May 27, 2010

* * *

DAS: What can you tell me about your last novel, Rue Darwin, published by Gallimard in September 2011?

Rue Darwin is to some extent that quest to bring that world back, to find my true self in it and look for answers to questions I have always asked about my country, its peoples, my origins, my family, and about myself, that elusive unknown within each person.

BS: Darwin Street is located in a poor and densely populated district in Algiers called Belcourt. In one of its streets, at 93, rue de Lyon, Albert Camus’s family used to live inside an old building. If we were the same age, Albert Camus and I would have been friends; we would have gone to the same school since our two streets are very close. In the 1970s, years after Algeria became independent in July 1962—I was then in my twenties—his novel L’étranger came into my hands. As soon as I read it, it was a revelation for me: Camus was evoking a world in which I had been living but which had utterly vanished. It is a strange feeling to find out that the world in which you were born and had been living for all your childhood has disappeared. One is obviously tempted to embark on the quest for that forgotten world, in order to understand it, to discover why it has disappeared, and who the people who were living in it were. It is an adventure. Rue Darwin is to some extent a quest to bring that world back, to find my true self in it and look for answers to questions I have always asked about my country, its peoples, my origins, my family, and about myself, that elusive unknown within each person.

My intention was autobiographical, but the novel is not entirely so. It is the attempt to reconstitute an unknown story, hidden, caught in little pieces in the course of a life without questions or answers. My mother’s death unleashed the torrent of questions I have had accumulated in me all my life without being able to answer them, without being able to ask anyone about them.

The novel is in fact Yazid’s diary. The story starts when his mother dies of cancer in a Parisian hospital. All his siblings who left Algeria have converged there—one of his sisters lives in the United States, the other one lives in Canada, one brother lives in Paris, and another lives in Marseilles. All of them are present, except for the youngest brother who is somewhere in Afghanistan, lost on the paths of the Islamist jihad. Yazid, as if he were freed from an antique interdiction, starts questioning: “Who is my mother, who are my brothers and sisters, and who am I for them?” These questions will bring him back to Darwin Street, where he arrived at the age of eight, on a summer day in 1957, right in the midst of the Battle of Algiers during the Algerian war of independence, after having been kidnapped from his village. His abductor had given him over to a woman in tears, telling her, “Here is your son, woman,” and telling the child, “Here is your mother, give her a kiss.”

DAS: Is there an autobiographical element in your novel? Did you really compose it when your mother died? Are you the author or just the narrator?

BS: My intention was autobiographical, but the novel is not entirely so. It is the attempt to reconstitute an unknown story, hidden, caught in little pieces in the course of a life without questions or answers. My mother’s death unleashed the torrent of questions I have had accumulated in me all my life without being able to answer them, without being able to ask anyone about them. To avoid frictions in the family, I have disguised many things, albeit remaining in the straight thread of truth as I perceived it. I am the narrator and the author, at times more the narrator and at times more the author.

DAS: Is there a reason why Hédi, the young Taliban brother whom you write “had been debrained by school and disembodied by the mosque,” was not present among his siblings at his mother’s bedside? Do you mean he is not part of the older world evoked in Rue Darwin? Does he represent another Algeria, the one that the new Islam destroys, not the more tolerant, original Islam that was present in Algeria before? Are you pessimistic, and do you consider him the future of Algeria?

BS: First, it was a reality: Hédi was physically absent. He was also mentally absent. Islamists are like Jehovah’s Witnesses: they disown all who are different from them, even their own families. Contrary to the other Arab countries in which the Islamic tradition had always remained alive, in French-colonized Algeria, for a century and a half, it either disappeared or was dimmed. Islam as the state religion, Islamism as a mass culture, is all new in Algeria. It came later, after independence in 1962, maybe even much later, since independent Algeria was first a people’s socialist and secular republic. Religion came back in full force in the 1980s, but only after President Boumediene died, as he wanted to be the Algerian Atatürk. The religious and sanctimonious explosion in the 1980s and ’90s was in a way the aftermath of colonization, which had denied the Algerians their fundamental identity and cultural values, and of socialist materialism, which by and large failed to bring the Algerians a better life. There was a will to catch up with the cultural values that had been left out during 132 years of French colonization and twenty years of socialist materialism.

In the Arab world, women’s resistance always stayed within the grounds of tradition, jihad, or refusal to change. Even when they fight for modern issues like work, sexuality, abortion, etc., they always base their demands on strict respect of tradition. But the Arab world needs revolution, not compromise, to enter modernity and be open to the universe, the other, the unknown.

It is hard to be optimistic for Algeria and the Arab world. If you consider the fast and faster evolution of the world in the last two centuries, you can say the Arab world has failed to keep up. The train goes too fast to catch up, and it reacts in vexed and angry modes, and also in disdain, as it makes of its failure a success, the success of having avoided a civilization deemed deadly by its own standards. All the speeches one hears in the Arab world year-round can be summed up thus: “The Judeo-Christian civilization, secular and materialistic, is deadly, Islam is Purity and Truth, and we are the best.”

DAS: Does the mother in a coma represent the Algeria of today, and her children scattered to the four corners of the world the contemporary Algerian diaspora?

BS: It is a beautiful image, and it corresponds to reality as I perceive it. The Algeria of history (deeply embedded in that of the western Mediterranean entity) does not exist anymore. There is a new Algeria, born in convulsion and pain. This is a fake Algeria, rootless, without veritable links to the Western world (object of myth to some, and of disdain to others) or to the Oriental world (an Orient of fairy tale, extremely idealized). Immigrants often give me the impression of being lost children looking for their parents.

DAS: Conversely, do Djeda, Yazid’s powerful grandmother, and her phalanstery represent French colonization, with its ramifications in the Maghreb and its possessions in the Métropole, notably in Vichy (a veiled reference to the Vichy government during World War II)?[6]

BS: Djeda and her phalanstery are the temporary products of a particular story. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, colonization brutally superimposed the modern world from France, Europe, and the Western world on a world already ruined long before: the Arab Empire to which Algeria had been joined had disappeared. The Ottoman Empire that controlled it had abandoned it to Barbary. The country was divided up into Ottoman principalities loosely attached to the Sublime Porte[7]. The indigenous population consisted of a mosaic of tribes without relations among them. For a few tribes whose living environment and economic system changed drastically on account of colonization, like the famous case of the Ouled Naïl tribe, for example, their means of survival were prostitution. It so happened that in France at that period of time, prostitution had been legalized and organized, hence the abundance of the “tolerance houses,” as they were called, in all the French colonial empire, and notably in West Africa and in the Maghreb.

DAS: Daoud-David is Yazid’s friend in his past life at the phalanstery, and one only discovers the truth about both at the end of the novel. Daoud’s hotel-management school friend, Jean, is a Jew whose family suffered from Nazi persecutions and concentration camps. To be with Jean and bask in the warmth of his family, Daoud willingly gets a job at the Lutetia Hotel in Paris, a place full of history for Occupied France and for Jews. His singularity as a homosexual was too heavy in the Muslim world; he changes his name to David and finds a new serenity away from his family. Is he also part of that vanished, pre-independence world in which other cultures and religions lived side by side?

BS: In the Arab-Muslim world, singularity is banned. It is regarded as a serious crime when it is contrary to the regulations of dogma. When individuals show that singularity, society drives them away or persecutes them and can even sometimes kill them. When a singularity is the common feature of a group, society invents mechanisms that emphasize this singularity to make of it a self-excluding phenomenon. For example, the prostitutes: it was enough to declare them non-Muslims not to have to judge them or castigate them according to Shari’a law. The same was true for Jews: suffice it to declare them dhimmis [“protégés,” i.e., members of tolerated religions subordinate to Islam] to put up with their presence.

You need to go into exile to live your singularity in peace, but it is not sure that the exile opens your mind to other cultures, other religions. The fast-expanding phenomenon of communitarianism in exile shows that exile can be a larger confinement that in the end leads you to seek what you have just fled.

DAS: Women in Djeda’s empire represent economic power in your novel, in contrast to men, who often hold inferior functions. On the other hand, they are strong and can survive even in difficult times. Are they the only positive characters in the novel, insofar as they survive every war?

BS: One can observe, in undermined societies, that women are the ones who are able to save the situation. They are men’s resource when they lose strength, virility, or are unable, or even unwilling, to fight anymore. During the civil war in the 1990s, which deeply shattered Algerian society, it is the women who prevented it from collapsing. They were admirable.

But often, our women’s resilience can stem from their refusal to see the world change, and they can weaken a tribe’s achievement. Resistance to change can prevent evolution. In the Arab world, women’s resistance always stayed within the grounds of tradition, jihad, or refusal to change. Even when they fight for modern issues like work, sexuality, abortion, etc., they always base their demands on strict respect of tradition. But the Arab world needs revolution, not compromise, to enter modernity and be open to the universe, the other, the unknown.

DAS: You frequently mention war in the novel (and peace even more). You repeat several times that “a war that does not bring on a better peace is not a war but violence against humanity and God.” Which war are you alluding to, the war of independence or the civil war brought on by the Islamists? What is the “1,000 Year War” you mention elsewhere?

BS: I am talking about all wars, in Algeria and elsewhere. A war for independence that brings about more violence and injustice than it did away with is a bad war. A war of liberation that submits the country to bloodthirsty dictators is not a good war. A war is judged by its fruits. If they are deadly, it means we did not fight the good war. One fights for peace, and peace has for its values freedom, solidarity, equality of rights and opportunity, etc.

“The 1,000-Year War” is an image to describe the war that never stops, and which will never stop, war in the name of religion.

DAS: “The more deaths, the more beautiful the victory.” “The Arab soil is thirsty for blood and Muslim people want martyrs” (pp. 116 and 117). These are a few of the sentences President Boumedienne shouted in a speech relaying the bad news and trying to make Algerians accept the Arabs’ defeat in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. They still shock you thirty years later because of the message of death they carry.

BS: Here is a perfect example of a bad war. Its aim was not to liberate the occupied territories and give the Palestinians a homeland and a state; its only goal was to erase the shame incurred by all the military defeats since 1948 by the coalesced Arab armies. The aim was not even to win that war, but only to show that Arab armies were at least able to win one battle. To this day, in all Arab military schools, people are ecstatic about the Egyptian army’s feat of managing to get across the Suez Canal and break the Bar Lev defense line, famous for being impenetrable. The rest, the defeat, the dead, the ruins, are not important, honor was cleansed.

DAS: Before Yazid discovers in the end his real identity, he has broached many topics, which probably are your own thoughts about numerous issues on the conditions of Algeria and your fellow citizens before and after independence, and now after the civil war. Was his story a pretext?

BS: To look for your history and your identity is also to look for others’ history and identity. You live in a country, an epoch, with people. You cannot know yourself away from this environment. When you get ahead in your research, you discover that your individual history is nothing, only a rustle in general history. The feeling of belonging to a people, of having an identity, is born from it.

July 29, 2012

Translation from the French

By Dinah Assouline Stillman

1 Le Prix du roman arabe (the Arab novel award) is a prize created in 2008 by Arab ambassadors in France for an Arab novel written in French or translated in French. The elected works seemed, up to June 2012, to be chosen for their high literary qualities in spite of interdictions suffered by the writers because of their contents. It had already rewarded such excellent writers as Elias Khoury, Gamal Hitany, Rachid Boudjedra, and, in 2011, Hanan Al-Shaykh with Toute une histoire (Eng. The Locust and the Bird: My Mother’s Story, 2009). Al-Shaykh is a well-known Lebanese novelist living in exile in London, whose many books denouncing women’s conditions in Muslim societies have been forbidden in Arab countries.

2 However he did receive money from a generous and anonymous donor, then gave it to the association “Un cœur pour la Paix” (A Heart for Peace), which is composed of French, Israeli, and Palestinian doctors who treat Palestinian children from Gaza and West Bank with heart defects.

3 Grand Prix SGDL (Société des Gens de Lettres) du Roman.

4 Translator’s note: This interview occurred before the Arab Spring.

5 On July 16–17, 1942, 13,152 Jewish, men, women, and children were rounded up in Paris by the French police, collaborating with the Nazi occupiers, and most were sent to the Vélodrome d’Hiver, a Parisian winter cycling stadium, in which they were held for a few days without food or drink. They were carted off to three detention camps, Drancy, Beaune-la-Rolande, and Pithiviers. They were eventually deported to be gassed at Auschwitz, first the men, then the women, and a few weeks later the children. The French government only acknowledged French responsibility with then-President Chirac’s famous speech in July 1995. In 2010, at the time of our first interview, two new French films were released that directly dealt with the Vel’ d’Hiv roundup, La rafle (The roundup, dir. Roselyne Bosch) and Elle s’appelait Sarah (Sarah’s key, dir. Gilles Paquet-Brenner). More recently, newly elected socialist president François Hollande also made a speech on July 22, 2012, for the seventieth commemoration of the event, expressing his commitment to remembering this crime “committed in France by France,” which created a controversy by Hollande’s not having insisted on separating Maréchal Pétain’s Vichy France from De Gaulle’s Resistance France.

6 A phalanstery is a kind of building or compound designed for a utopian, self-contained society envisioned by the nineteenth-century French utopian Charles Fourier, in which everyone lives according to the same social rules. It is designed to integrate urban and rural features, and is composed of three buildings, just like in the novel: the main living quarters, a building for the children, and the “business” house of the prostitutes.

7 The Sublime Porte was the official diplomatic name for the Ottoman Imperial Court.