A Conversation with Illustrator David Small

Introduction by Elizabeth R. Baer

The following interview was conducted by Julia Tindell, a student in a course I taught at Gustavus Adolphus College in fall 2010. English 201, “The Art of Interpretation,” is considered the “gateway” course for the English major. Despite its somewhat artsy title, the course is intended to serve as a hard-core introduction to literary theory for our undergraduates. For course texts, I use an anthology of essays and excerpts of theorists from Sigmund Freud and Cleanth Brooks to Jacques Lacan and Judith Butler. I accompany this with another text that explains the schools of theory in straightforward language. Each time I teach the course, I change up the two novels I use: one a canonical text (Kate Chopin’s The Awakening and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein have been recent choices) and the other something so recently published that little, if any, critical material is available yet. The canonical text we read in a Norton or Bedford critical edition.

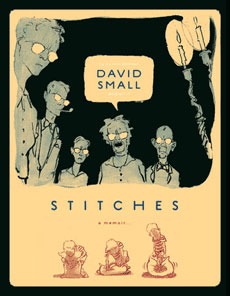

When I taught the course in fall 2010, I chose a newly published graphic narrative, Stitches, by David Small. Small has illustrated dozens of children’s books and has won the prestigious Caldecott Medal, but this was his first effort for adults and his first graphic novel. Stitches is an autobiography that delineates Small’s remarkably dysfunctional childhood. He grew up in the Motor City, his father a physician and his mother a closeted lesbian. The title of the graphic narrative functions in several valences but, most importantly, references the literal stitches Small had after surgery for cancer at age fourteen, a surgery that had been cruelly delayed by his uncaring parents. Small uses Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland as an intertext throughout the narrative, which works beautifully as his childhood was as bizarre as Alice’s life down the rabbit hole.

Only a few of my students had previously read graphic narratives, but to a person they loved this book. They resonated with the parent/child conflict depicted in the memoir, and they were astonished by the interplay of text and image and how that interplay enriched their reading experience. As I have done in several earlier versions of this class, I engaged the students near the end of the term in creating our own “critical edition” of Stitches. Each student was asked to contribute an essay, using a theoretical perspective we had studied. They were also asked to take on an additional assignment such as writing a brief bio, designing the cover, or serving as editor of the volume. Our college library agreed to shelve the resulting “book.”

When I suggested that someone in the class might try to contact David Small to see if he would agree to do an interview, Julia Tindell took up the challenge and kept at it with tenacity. We were all amazed when Small not only agreed but provided, electronically, generous and thoughtful responses to the questions Julia and the class posed. When our critical edition was complete, we sent a copy to David Small himself. His reply was heartfelt: “That my book sparked these thoughts and insights makes me so happy. Their pages have already given me some new insights as well, not to mention made me feel that I may have actually done something really worthwhile. I can't tell you what a huge tribute this is to have and to cherish.”

David Small has kindly granted permission for this interview to appear in World Literature Today, and added a postscript in November 2011.

Julia Tindell: What would you want college students reading this book to know?

David Small: When all is said and done, and in a general sense, Stitches is a warning about wrongheaded family traditions. I see my own family as this long, long conga line of people, all doing the same dance, generation after generation, everyone abusing the person ahead in the same ways they were abused by those behind them.

I stepped out of that line, but I still know the dance by heart. It is a daily struggle not to do it with the people around me, whom I love.

JT: Was there any part of the story in particular that you felt really epitomized your childhood/adolescence?

DS: Three parts:

1. The little man in the jar. I did not see him as a fetus (not at six, because I didn’t know what that was). I saw him as myself, my Mini-Me. Like myself at six, he was an angry little thing confined in a jar full of murk. It was that which terrified me, which infected my dreams for decades, and which made that memory—the first memory I ever wrote about—stick with me all those years.

2. My mother giving me Lolita (a forbidden book) the night before my operation, then her stealing it back when I was in recovery. That was pure treachery and pure confusion for a fourteen-year-old. It sent me over the edge of sanity. Years after I had been in psychoanalysis, my analyst told me that his first diagnosis of me was “mildly schizophrenic.” I believe it was that particular bit of weaselly behavior on my mother’s part that sent me into that state, where I began to hear voices.

3. My parents continuing to act duplicitously even when they were confronted with the truth. This was totalitarianism. This is what drove me away from home when I was only a kid of sixteen.

I wasn’t prepared to live on my own, but it was the only way to escape the insanity of that household.

Of course it didn't escape me that the White Rabbit led Alice down into a hole in the earth, and that down there (or in there), things were strange. I had spent enough time looking at X-rays to know we have a world inside of us.

JT: How did you become introduced to the Alice books as a child? Why do you think they had such a profound effect on you?

DS: As a child, I knew only the Disney movie. I was a total Disney freak as a kid. (Not the way kids are today. This was before TV and DVDs. I only got to see his films when they came into the theaters, once every five years or so.) I didn’t read Alice in the original until much later.

The candy-colored Disney images offered the kind of escape I really wanted and needed as a kid. Of course it didn’t escape me that the White Rabbit led Alice down into a hole in the earth, and that down there (or in there), things were strange. I had spent enough time looking at X-rays to know we have a world inside of us. I mixed that up with Wonderland and thought somehow I could turn myself inside out and get into it.

JT: You said in a previous interview that you found a lot of creativity in writing before you became an artist and illustrator. What was challenging (or enjoyable) about mixing the two media of text and imagery in a graphic novel?

DS: I should have said that my first serious creative impulses were tried out through playwriting. I actually found a lot of frustration in writing. The thing I wanted, above all, was to speak out, and the theater seemed the perfect place to put it all out there, under the hot lights, for everyone to see. But having been trained in my family to keep my mouth shut and to have no opinions, I didn’t really know how to communicate. I just imitated those who could: Harold Pinter, Tennessee Williams, and Edward Albee primarily.

Anyway, when I found out how much easier and more natural it was for me to draw, to create worlds two-dimensionally, on paper, I happily gave that up.

I actually thought of Stitches as a little film, or a storyboard for one. Of course, Stitches is not a film, it’s totally a book, but it’s a book heavily influenced by cinema.

I’ve studied film, enviously, as a serious art form since the 1960s. It gave me tremendous pleasure to be able to get this close to filmmaking.

What I wanted was to tell the truth, which somehow, suddenly, was incompatible with what I do for a living, which is making art. Art is inherently a falsification because it pares away all the dross, all the garbage that life drags structurally in its wake, but by doing that it can clarify everything as well.

JT: What did you intend the role of the text to play in expressing your story?

DS: As an illustrator of picture books, I know that the text is there to tell what the pictures can’t, and vice versa. They augment one another. Using both words and pictures, it’s possible to tell two concurrent stories, which are like two rivers of oil of different viscosities, flowing along at the same rate and in the same direction, but which never really mix.

The deeper I got into making Stitches, the more I tried to pare the text down to a bare minimum. It is, after all, a story about speechlessness. But text was absolutely essential. Exposition, for one thing, is a nightmare if you try to do it in pictures alone—as in telling who is related to whom, where we went and why we went there, and so on. That kind of information is so tedious to try and communicate visually. For this kind of information—and for dialogue—you really have to use words.

The way I was using text completely wrongly, in the beginning, and which I tried to eliminate completely, was in delivering opinions and judgments on what was going on. This is bad. I had to constantly castigate myself: “Let the reader make up his own mind. Stop showing how goddamn canny you are! Stop handing out decrees, like, in little envelopes on a silver platter! Ugh!”

As I’ve said in other interviews, I finally took my tone from the memoirs of Holocaust survivors. In those works the facts speak for themselves, and there is no need for judgmental embellishment.

I respect literature as the highest art form, but I respect film and photography, because they can so quickly and so economically dive beneath the surface of events and show the brutal truth of what’s going on. This equates with the way I grew up, silently watching from the sidelines, and learning from this to detect the whole firmament of other meaning behind language.

For example, I had to develop my skills in reading body language and nuance as a survival tactic in our household. If Mother had “that look,” you got out of the way fast. Then, the next moment, you would hear her chirping away to a friend on the telephone, talking about how everything was “fine” and how “happy and healthy” we all were.

This is familiar stuff to most anyone who grew up middle class, yes? But to a child who is imprisoned in a sick, totalitarian household, who has no control, it’s . . . well, it’s crazy-making. (I was about to say, “It’s terrifying,” but it’s not. For a kid who doesn’t—who can’t—know anything about the world, it’s just the state of things.)

Judging by the response to it, Stitches seems to have touched on a certain kind of middle-class angst. I mean, there are all kinds of child abuse, not just the sensational kind involving broken limbs or being locked up in a cellar. There is a more subtle, more widespread kind of abuse, and it’s very insidious, with long-lasting and possibly dangerous effects.

I recall once, as a teenager, actually begging my mother and father to hit me, to actually show their anger in some solid, physically demonstrable way. At least then I would have known something, could have been sure of something. But this controlled, discrete, middle-class withholding of their very real, very palpable anger—which was constant in my mother—made me begin to doubt my own perceptions of reality. Meanwhile, they never had to face their own fury.

All that was rather roundabout, sorry, but it was meant to answer more extensively your question about words and images.

JT: What was most challenging about organizing your memories into a coherent plot? How did you go about it?

DS: That was the most taxing part of making the book. How to organize a life. It’s really an impossible task! I think if I had not had a contract and a deadline I never could have brought myself to do it. (Contracts and deadlines can clear up cowardice—fast!—like having bullets zinging over your head.)

Seriously, there was something that seemed false about giving shape—artistically—to something that seemed so formless and so chaotic as my own life. What I wanted was to tell the truth, which somehow, suddenly, was incompatible with what I do for a living, which is making art. I was also conscious of the (then) huge controversies surrounding autobiography, and I didn’t want any shades of suspicion hanging over my work. So anything—any little thing—that felt to me like an alteration of the reality of things-as-they-actually-happened, even contemplating doing anything like that, send me into paroxysms of guilt. It paralyzed my hand.

In the end, of course—as any memoirist absolutely has to do in order to make their story comprehensible—I eliminated several people and rearranged the order of certain events, in order to make the story flow and to make it understandable to a reader. To protect some innocent people I changed some names and—since the story is also drawn—some faces as well. And, as it turns out, it was ALL OKAY on the moral level that I was so worried about! The whole point was verisimilitude, not a slavish listing of facts.

Art is inherently a falsification because it pares away all the dross, all the garbage that life drags structurally in its wake, but by doing that it can clarify everything as well.

JT: Do you have any history with dream analysis? If yes, could you please describe it in relation to Stitches?

DS: I see my dreams as a continuum of my waking life, so they just naturally found their way into my autobiography. I had to lay the groundwork for them in Stitches, to bring them in at the correct moment, otherwise they would have been as confusing and as boring as anyone telling you their dream generally is. Without the context from waking life, the dream may be fantastic but it’s totally meaningless.

I have kept a journal of my dreams since I was in my late twenties. (That’s forty-plus years of dreams!) From my analyst and through a little reading of Freud, Cirlot, and others, I learned enough about dream symbolism and about the way we twist language into imagery in our dreams to begin to make sense of their fundamentally nonsensical metaphors.

Some dreams resist interpretation. Or rather, I resist interpreting them because they are such great stories; I don’t care to diffuse their power with total clarification. I say this to distinguish this—what to call it? “Mystery Storage,” maybe?—from pure avoidance. Our dreams—the most vivid of them—carry urgent messages for us to decipher, if we care to. If there is a real and present need to interpret a dream, I can generally do it, because to be able to live one’s life effectively should precede making art of it. Although that is arguable . . .

In fairytales, you'll notice, it's never the actual mother but always the stepmother who is evil. This is a convenient displacement, because the idea—for me, the fact—of an unloving mother is so psychologically unbearable to so many people.

JT: Many of my classmates have expressed the thought that your mother isn’t portrayed very sympathetically in this piece. How would you describe her representation in the book?

DS: If my mother comes off as unsympathetic to some readers, I accept that as inevitable.

When my older brother read the book he said it was a snapshot of his own youth. Our parents, the way I depicted them, were exactly the way he remembers them, which was, for me, a great affirmation of my own perceptions.

I know my mother was not a monster but a person with very real problems. I actually tried very hard to find a sympathetic way of portraying her. At one point—at about the twelfth draft of my book—I frightened my editor by telling him I was going to scrap the whole thing and start over, telling it from my mother’s side, because she was the one who had obviously had the real childhood trauma. But I quickly had to abandon that because it had suddenly become a work of fiction. I had to begin making stuff up because there was such scant factual information to go on. That was never my intent, to make anything up at all.

That threw me back into writing my own story from age six to sixteen, and in that story—the true one that I and my brother experienced—she was not a sympathetic character.

Ultimately, the only thing I could come up with to stir empathy for my mother in the reader was to show that photo of her in the epilogue. That picture of her—taken around 1921—is photographic evidence that she had been disturbed for a very long time. (Take another look at the fury and resentment in her posture and in those eyes.) This photo is the sort of thing I cherish in my family album, because the camera lens momentarily penetrated the façade. Actually, I could have chosen from any number of like photos of my mother, but that one—because she’s so young, so prettily dressed, and so vulnerable-looking, almost as if she’s trapped (which she was, in her own nutty family)—has a particular poignancy to it.

Along with the photo I listed all the things I know about her that might explain such a selfish and unloving character: her various illnesses, her secret homosexuality, and the rest.

Then, of course, there was her mother—my homicidal grandmother—and the people behind her. It’s just endless! They are all part of the conga line of family craziness.

I’m sorry to be so long-winded on this point, but I feel it’s a problem in our society, this inability to think of mothers as being wicked. In fairytales, you’ll notice, it’s never the actual mother but always the stepmother who is evil. This is a convenient displacement, because the idea—for me, the fact—of an unloving mother is so psychologically unbearable to so many people.

I’d ask you to go back and review Clytemnestra, Medea, Lady Macbeth, and Mrs. Bates in Psycho, to name just a few of the unsympathetic mothers in art. For me, these classic characters are embodiments of some very real women.

JT: How do you think your mother or father would have interpreted themselves if they had been writing this novel?

DS: My dad, I imagine, would have proudly listed his career accomplishments and talked reverently about his parents, even though his mother (my paternal grandmother, who does not appear in Stitches) was a strict, loveless dictator in her own right.

My mother, I’m thinking, would have talked about herself in terms of her accomplishments as a sportswoman on the golf links, and as secretary, then president, of the Women’s Hospital Auxiliary.

In public interviews my editor has advised me, regarding my parents, to use the phrase, “They did the best they knew how.” I concur. They really did do the best they knew how. The trouble was, they refused to listen to their hearts and to think for themselves. They simply repeated what their own families had done to them and they did the same to us.

One last thing: the only kind of real and effective forgiveness I know of is to try and understand the person who has harmed you as a human being. I’ve done that to my own satisfaction with my parents, and I acknowledge that, with all their faults—because of them, in fact—I am who I am, both for good and for ill.

Four follow-up questions

November 2011

JT: What were your thoughts on the students’ anthology?

DS: I don’t know much about how critical theory is generally taught, but it seems to me that Dr. Baer has a very original and successful approach. I was really so impressed with the essays, the heartfelt responses, all of which held validity for me personally, and the way each author—following their assignment—stuck faithfully to a different ideology.

JT: How has Stitches continued to affect your life and career since its publication?

DS: A friend of many years told me that since Stitches, it seems as if I’ve had shadow-removal surgery! (I do feel different, lighter.) In terms of my career, I think the publication of Stitches confused the children’s book world a bit. They thought they lost me. (They didn’t.)

JT: Do you foresee yourself writing more graphic novels in the future? If so, what sorts of topics will you explore?

JS: I have no idea. I have some favorite short stories that I thought might translate well to graphics, but each time I’ve tried I’ve found that I liked the texts so much it seemed like a violation to retell them in pictures.

JT: What are you working on now?

DS: I’m taking a break at the moment. I have two new picture books coming out next year and am excited and hopeful about both of them. One Cool Friend by Toni Buzzeo was published in January by Dial, and The Quiet Place by Sarah Stewart, my wife, will come out in September from Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

December 2010 / November 2011

Elizabeth R. Baer is a professor of English at Gustavus Adolphus College.