Memories Unmoored: A Review of In the Café of Lost Youth, by Patrick Modiano

Ever since he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2014, a deluge of Patrick Modiano’s work has found its way into English translation. Modiano’s novels have averaged at least two or three publications each year since 2014. This is good news for those who might not have heard of Modiano prior to his Nobel, which is most of us who live outside of France. This French author with an Italian last name has written some of the most powerful postwar narratives examining memory, place, and identity since Camus.

Ever since he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2014, a deluge of Patrick Modiano’s work has found its way into English translation. Modiano’s novels have averaged at least two or three publications each year since 2014. This is good news for those who might not have heard of Modiano prior to his Nobel, which is most of us who live outside of France. This French author with an Italian last name has written some of the most powerful postwar narratives examining memory, place, and identity since Camus.

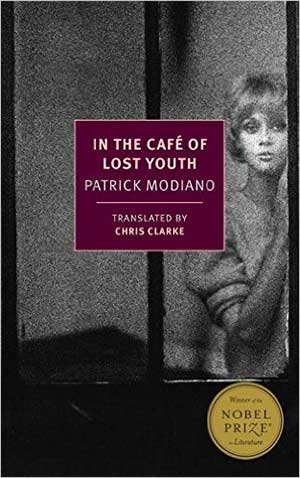

Modiano’s latest novel to be published in English is In the Café of Lost Youth (New York Review Books), first published in France by Gallimard in 2007. Like most of his novels, In the Café of Lost Youth is short enough to be read in one sitting, and that is exactly how one should read this book, preferably while sitting in the café of one’s choice. In the Café of Lost Youth hovers around the enigmatic young woman known as “Louki,” who wanders in and out of the lives of the novel’s various narrators. When we first encounter Louki we are told that there is nothing habitual about her. In fact, she haunts the narrative like a ghost or an ill-formed presence waiting to join the action, but for whatever reason, is not able to fully engage the other characters. “She wasn’t regular about her visits. You might find her sitting there very early in the morning. Or sometimes she appeared at midnight and stayed until closing time.”

But the central theme of the novel is not really Louki and her relationship to the narrators; instead it is the concept of “fixed points,” or lack thereof, in their lives. Reference points keep us moored to our respective realities, but as Modiano has shown throughout his work, all reference points become suspect in the postwar milieu, especially the ones we locate in memory. As such, the lives of his characters are constantly reimagined and refixed in the mesh of his narratives.

Modiano’s fictional world is not postapocalyptic, like the fictional worlds of Beckett, but postrelational . . . a world where familiar patterns, whether placed in memory, neighborhoods, or situations, are dispersed and left to languish on the wind.

What makes In the Café of Lost Youth special is its insistence that the reader pay attention to even the smallest of details, to its narrative patterns. As easily as Modiano is to read, he gives his readers a dark, threatening world, but in so subtle a fashion that we barely notice the threat. Modiano’s fictional world is not postapocalyptic, like the fictional worlds of Beckett, but postrelational. That is to say, Modiano gives us a world where familiar patterns, whether placed in memory, neighborhoods, or situations, are dispersed and left to languish on the wind. His characters are equally left to languish in a world where their relationships to other characters, to place, and to themselves, are no longer secure. In the Café of Lost Youth gives us a glimpse into a world where everything we thought was true becomes suspect, even the reader’s relationship to the text.

Southern New Hampshire University