July 2010 WLT

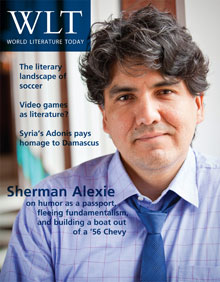

Sherman Alexie—poet, novelist, short-story author, screenwriter, film director, Spokane, Coeur d’Alene, comedian, and more—visited the University of Oklahoma campus in March as the 2010 Puterbaugh Fellow. It was an exciting time for OU as well as for Alexie. Just before he arrived, he learned he won the 2010 PEN/Faulkner Award for his latest short-story collection, War Dances, and while he was here, he was honored with the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas Lifetime Achievement Award. War Dances, like his recent poetry collection Face, continues the stylistic innovations and penetrating insights he introduced with the publication in the early 1990s of his first short stories in The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven, and his poems in The Business of Fancydancing. In the prolific interim, he has published several other story collections, three novels, numerous collections of poetry, and a novel for young adults (The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian) that won the National Book Award. In our conversation, he spoke of the pragmatics of Indian politics, the commercialization of art, his engagement with his critics, Sarah Palin, and much more with characteristic humor, acumen, and abandon. The following is an excerpt of our conversation.

Joshua B. Nelson: In your mind, what makes War Dances what it is? It seems to be doing something that not very many people are doing stylistically, in terms of form.

Sherman Alexie: It’s old-school, actually; it’s nothing new. War Dances is really a lot like my first book, The Business of Fancydancing, which was also a combination of stories and poems but reservation-centric. So you could think of War Dances as the urban equivalent of The Business of Fancydancing. I think that subject matter was exciting to people because at any given point, somewhere around 70 percent of Natives live off-reservation. And yet our literature doesn’t reflect that. Those amazing urban Indian stories are not being told, and I think War Dances makes a gesture toward that. So because there aren’t many of us, because we don’t have a huge body of literature, I think when one of us does something new it still feels revolutionary in the context of an art form that’s thousands of years old.

JN: You also do some other sort of smaller genre inclusions, almost like readers’ guides. You do a little bit of lit crit, a little bit of art crit. I’m interested in what you are up to there. I think, for instance, of “Fearful Symmetry,” of the critical engagements you’ve got there. You talk about an escape fire in that story and of writing about writer’s block as a way to get back to writing. I’m wondering if you’re maybe doing a little bit of escape-fire setting with your engagement with criticism.

SA: Honestly, that never even occurred to me. But it’s like in therapy when your therapist says something and you’re like, “Yeah, you’re right. Subconsciously, I must have been doing that.” Because it makes perfect sense. I mean, it was a story about escaping.

JN: And using up the fire before it gets to you.

SA: Yeah, using the fire to protect yourself from the fire, which is what English is all about for me. I think of Adrian Louis’s line of poetry about English hanging Indian tongues on its belt. What is the Joy Harjo title, Reinventing the Enemy’s Language? Yeah, that story is definitely part of such a tradition. Especially talking about cinema, which is where all the negative imagery, all the inaccurate imagery of Native Americans, comes from. So for a Native to be working in that genre is far more ironic, far more ludicrous than an Indian writing books. You know, writing an honest, truthful story about an experience but also satirizing myself and my process in it, with a capitulation to the colonial forces of Hollywood.

JN: And could we also say the capitalist forces?

SA: Oh yeah, definitely.

JN: On that point, do you find that sort of capitalist pressure might have something to do with the relentless innovation that you seem really to be practicing, even from The Business of Fancydancing? “Make it new” as one of the mantras of capitalism?

SA: It is true. You know, I’m an arrogant guy and sometimes I say things that make me sound like I’m some very arrogant guy, but I’m only arrogant. I’m not very arrogant. But I play with the big boys.

JN: And if you’re going to run with the big dogs—

SA: You better have your game on. I’m not writing in the equivalent of playing rat ball on the rez, you know. I’m not playing at some community college, you know, in Des Moines, Iowa. I’m on the court with the LeBron Jameses and the Carmelo Anthonys of the literary world. I’m like the white guy at the end of the bench that goes to the shopping malls and children’s hospitals, but I’m still on the court, so I have a whole other level of stuff to worry about.

JN: Do you find that it’s something you do indeed worry about? Is there some anxiety about a capitalist influence here for you?

SA: That’s interesting, because I wrote War Dances—which essentially is a small-press book, with small-press ambitions and a small-press aesthetic—as a purposeful antidote / reversal / response to the success of The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, which is a massive, worldwide success. Honestly, I never have to write another book again. I think I’ll probably be able to live on this book for the rest of my life, financially speaking. And the critical success, all the awards, all the attention—it was great, I loved it, but I also felt like, I’m not supposed to sell this much. So there’s some general suspicion in my mind.

JN: Some critics, like Elizabeth Cook-Lynn, have claimed that by not writing specifically to strengthen tribal political sovereignty, you’re engaging in a distracting or irrelevant artistic project. You respond with allegations that her judgment is clouded by a nostalgia for an irrecoverable past. Let me ask you about the linkage of political power and nostalgia, and maybe you could talk generally about what you mean when you talk about nostalgia.

SA: Number one, we’re not getting it back. [pause] We’re not getting it back.

JN: Land, specifically? Culture?

SA: Language, culture, who we were when Europeans arrived.

JN: Are you convinced that Native languages, for instance, will be gone?

SA: If your tribe isn’t big enough, yeah. You know, there’s probably a critical mass, what would that be, probably ten thousand?* Maybe even bigger. Might be like fifty thousand, so after a while, the only languages that are going to be alive are those that are isolated enough—Hopi, Navajo, Cherokee. It’s an issue of population base. Earlier, I talked about the loss of language—essentially, she is blaming the victims. That’s what I see a lot of Native scholars doing—blaming the victims. Blaming the loss of culture on the people who had the culture taken from them and blaming their descendants because we are not recovering something. It’s always interesting to me, too, the essential fallacy of engaging in literary and political and cultural criticism and pretending that it’s indigenous. You know, Liz Cook-Lynn is utterly incapable of irony, of understanding irony, of even seeing the ironic nature of her own existence. So, the stances she has are a kind of fundamentalism that actually drove me off my reservation. I think it’s a kind of fundamentalism about Indian identity, and what “Indian” can be and mean, that damages Indians.

JN: Let me ask you about the political side of her argument, which is perhaps a little bit less fundamentalist and more engaged with a practical kind of development of sovereign power and that sort of thing. Do you find that one can engage in that as an Indian?

SA: But it’s never about culture. It’s always economic sovereignty. Native American sovereignty is expressed in terms of casinos, cigarettes, fireworks. It’s engaged in exploitation, almost always engaged in the worst parts of capitalism. You know, the exploitation of human weakness. That’s how our sovereignty gets most expressed.

JN: What if we were to substitute a charged term like sovereignty with something like volition or maybe agency or self-determination or just, you know, doing what you want to do?

SA: None of which we have.

JN: Let me ask you, where would you like to have it?

SA: Our sovereignty is alleged sovereignty.

JN: Where would you like to see it developed? What shape would you give it?

SA: I mean, I get words put in my mouth. People think I call for the disbanding of Indian tribes. It was on the web for a while that I gave some talk about the abolition of reservations, which is not true. It’s an overall philosophical difference rather than a bureaucratic one. I mean, we’ve done it forever. Native leaders used to become leaders by accomplishment. You think of the great leaders of our past, the famous ones. You think about Sitting Bull, Geronimo, or in my tribe Lot, these amazing men and women, who did it through actual accomplishments, through intellectual engagement, through spiritual philosophy, through war, through real-world problem-solving.

JN: And now they might take the shape of?

SA: High school dropouts.

JN: If we were to look for leaders now, what sort of accomplishments—

SA: College education. It’s a complicated world, you know. Because of economic sovereignty, Indian tribes are multimillion-dollar corporations, and we’re often sending the leaders of those corporations out into the business world without high school diplomas. How can we not be manipulated? How can we not be abused? How can we not be stolen from? We’re not sending our best people out. And the anti-intellectualism that exists, these periodic waves of it in the United States, has risen in the form of Sarah Palin, Glenn Beck, and the Tea Party folks. I recognize it instantly because Indians have always had it, at least in the twentieth century. There’s an anti-intellectualism on Indian reservations, inside Indian communities. That didn’t use to be the case. I know Sarah Palin, you know. My tribe is run by Sarah Palins.

JN: Can she see your reservation from Alaska?

SA: She can see everything from Alaska. So it’s no accident she’s married to a guy who is part Indian. You know the funny thing, in terms of an overall political/artistic aesthetic, in the United States, you would call me a lefty. I’m a progressive, a social democrat. I’m a Swedish guy hidden inside the body of a reservation Indian boy. But in the Indian world, you know I’m this weird sort of libertarian. I’m always amazed how white folks think Indians are these free-living ——. There are more rules to being Indian than inside an Edith Wharton novel about which fork to use at dinner. The social pressures, the social rules inside the Indian world, and the essential conservatism, big C and little c, of Indian people, is something that outsiders rarely understand. I mean, Indian communities are theocracies.

JN: That’s quite right.

SA: Their governments are Third World banana republics. So I fled. What I was, essentially, was a guy who built a boat out of a ’56 Chevy and made my way to the Florida Keys. That’s what I was in —the indigenous version of the Mayflower. I was fleeing religious persecution.

JN: Which is certainly the subject of, and no small part of, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian. To jump back quickly, when I pressed you about examples of modern-day sovereignty, or modern-day leaders, and hearing you talk about intellectuals as being potential leaders in this regard, I don’t think it would be much of a stretch to say that authors could fulfill such a role.

SA: Yeah, that’s gonna happen.

JN: We hope so, at least there are some kids buying books, right?

SA: But the thing is, this great country we live in was founded by intellectuals—flawed humans but amazing intellectuals. Slave-owning intellectuals, but Jefferson, Adams were brilliant, Abraham Lincoln, brilliant, and they were rewarded and celebrated for their brilliance. [. . .]

JN: Thinking generally about the moral message of your writing in many places, as in Flight, for instance, you talk about responsibilities that we have with others. Could you talk a little bit about how you understand what those responsibilities are, and if you think there are things, especially in American Indian communities, that are clouding our understanding of how we ought to be relating hospitably with others?

SA: We like to think that our condition is special, that our oppression, our poverty, our situation, is special. It’s really not. Every problem in the Indian world can be directly related to poverty. Every problem we have is a variation of the same problem poor people all over the United States have, and we can suggest all these cultural solutions: somebody powwows more, they’re gonna be better; they dance more, they drum, they’re gonna be better. And that could very well be the case for that individual, but as a group of people, it really is about economic advancement. We live in a capitalistic society, and that’s not going away. So it really comes down to: How do I get that better job? How do I lessen the distance between my income and the income of the upper class, because there are very few of them doing anything about lessening the distance.

You know that is not how the United States works anymore. It used to be this country had a stronger sense of social responsibility, that the difference between upper-class income and lower-class income was not exponential like it is now. You think of all the philanthropy that rich people did. Sure, they were slave-owning, Indian-killing, evil bastards, but they were philanthropic in a way that today’s people are not. The ironies are astounding in that. I mean, have you heard of the Google Foundation? Have you heard of the Facebook Foundation for Social Change? Have you heard of the Apple Foundation for Social Change? The Steve Jobs Foundation?

JN: No, but I’ve seen the iPad.

SA: The only one is Bill Gates. So the only one behaving like an old-time, morally responsible billionaire in the United States right now is Bill Gates, and the fact that he is doing it while he’s alive is also very different. So, they’re not going to do anything about it. The whole government now is set up—the way people get elected now, Democrats and Republicans—to ensure that the rich stay rich. And so the only way to improve your life and the life of our people is through our own individual efforts to educate ourselves and get better jobs. You know that’s one of the reasons why, when I come to colleges and I meet Indian students, I celebrate them because nobody celebrates them. When was the last time you saw an honor dance for college graduates at a powwow? [. . .]

JN: One of the things I’d like to ask you about is about your penchant for controversy. You’re quite good at saying things that people are gonna notice, yes?

SA: Well, I say things that I believe.

JN: In hyperbolic ways, sometimes?

SA: Well, yeah, sometimes. It’s part of my binary, pathological, lying nature, I think, but I’m a performer. Even in my interview in the Washington Post recently about winning the PEN/Faulkner, Jacqueline Trescott didn’t put in the punch line. I said, the people who’ve won this award are legendary, and I feel, wow, I’m a part of that, but the punch line was, yeah, I’m like the adult at the kids’ table at Thanksgiving. And that punch line didn’t get put in, so it makes me sound like an arrogant asshole. So I’m sure I’m gonna get all sorts of e-mails about what an arrogant asshole I am. And I’ll go yeah, but not that arrogant. And then once again they’ll miss the irony in that.

So, the point is that in public discourse, people don’t read well, people don’t listen well, people don’t engage with an entire argument. They’ve been taught by what journalism has become, what political discourse has become. They’ve been taught how to pull out quotes to argue with. Not the totality of an argument. Not the philosophies behind the argument, you know. I don’t even try to engage them in a certain way, by quoting Oakeshott or Keynes. I don’t even try that because it’s pointless. So you try to filter these philosophies that you are educated about through the things you’re talking about, and I try to do it in a twenty-first-century pop culture way. And it’s not that I’m so much smarter than everybody; I just read a couple more books.

JN: And aren’t you using irony quite a bit to accomplish this goal?

SA: That’s the American way of talking. It’s our language.

JN: But it seems to be one that some people are having some difficulty with.

SA: Well number one, being funny, people think you’re not being serious. Humor when used politically always goes after people with more power and systems and institutions that have more power. The problem comes when it’s a joke about somebody with less power than you, and so you have to be very careful with that stuff. Not to say that I don’t mock people with less power, but you always have to be hyperaware of that.

JN: But it’s not about keeping them disempowered, for instance.

SA: No. It’s a way of talking about them, because we all self-mock. And so it’s a way of joining their tribe. I can speak to any audience of any political persuasion because I’m funny, you know. Give me twenty minutes—and I’ve done it with a conservative crowd. I’ll have them laughing at Jesus jokes. And so it’s really a passport into other people’s cultures. A temporary visa.

JN: There you go. A green card.

SA: Humor is my green card.

March 2010