A Conversation with Dacia Maraini

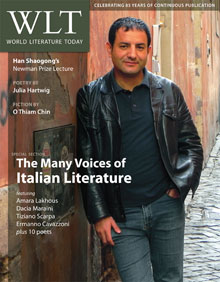

Following the performance of her play Mary Stuart at the University of Oklahoma this Spring, Dacia Maraini invited the director, Susan Shaughnessy, and the actresses who performed the roles of Mary Stuart and Queen Elizabeth, Anna Fearheiley and Emily Jackson, to perform the play at the Festival delle Due Rocche in Arona, Italy, in September 2011. Photo credit: Yousef Khanfar

Arenowned novelist, playwright, essayist, and social activist, Dacia Maraini is one of the most important voices in Italian culture today, just as she has been for the past many decades. In March of this year, Maraini visited the campus of the University of Oklahoma to meet with the OU community and attend a performance of her 1980 play Mary Stuart. We were lucky to have two days with her, discussing her craft as well as her thoughts on Italian society past and present. On the final afternoon of her visit, I had the opportunity to sit down with Maraini and ask about her rich career, her relationship to Italian society, and her most recent publication, La seduzione dell'altrove (The seduction of the elsewhere), a collection of reflective travel essays published by Rizzoli in 2010.

Monica Seger: Your first novel, La vacanza, was published in 1962, almost fifty years ago now (see Books Abroad, Summer 1962, 311). How would you say your writing has changed over time?

Dacia Maraini: Well, I think I'm rather faithful to myself. I haven't changed much, but certainly the world has changed around me. You have to deal with the mutability of the world, and so, as I consider myself a witness of my time, I have to speak about what I have in front of me, and those things are changing a lot. The world changes so quickly that you don't have time to adjust. I believe that I have a fidelity to my profound being and my profound style and way of looking at the world, and my way of dealing with the world outside.

MS: So in spite of changed circumstances in the world, the same questions are ultimately at stake for you?

DM: Oh yes, I would say that for me the relationship between the person and the collective—meaning the political, not political in the sense of parties but ethical—those fundamental values are there. So things can change, but what, for example, is freedom? And what is the relationship between the limits of your freedom and the freedom of others? That is the basis of ethics. And what is . . . violence? And to what extent can violence be accepted in society, or what is the relation between sexes, between genders, or what does writing mean, or what does it mean to be engaged? You know, these are the fundamental issues.

MS: Something else that remains constant in your work is your relationship to language, your use of a gentle, rhythmic tone to pull the reader in. To make a reference to the title of your latest work, La seduzione dell'altrove, what is the role of seduction for you in crafting a literary work?

DM: Well, you know, I think that the literary process is very near to music. In every literary project, poetical or even prose, you deal with rhythm, as you said, and rhythm is music. So I think that you differentiate one author from another from the rhythm and the musicality that is behind their style, and I think that what captures the attention of a reader is not the subject. You can have a wonderful subject, but you can't reach the attention of the reader if you don't have a musical construction.

MS: You have spoken of the relationship between a playwright and her public, and the important role of the audience in the theater. How does the author fit into that discourse? What do you perceive the relationship to be with readers as you write a book, and does that affect its formation?

DM: Well, I think the relationship with the public is much more important in the theater because, first of all, you deal with a group—actors, directors, technicians—so, you know, it is a really collective work. And then you have the public there, and it is a live public, and a public that changes every evening and can be participating or not—you can feel it. On the contrary, if you write a book you are alone, and you are alone with the reader. It's a much more personal relationship. It's not so collective, it's not so social, you see. So you have to speak to the mind of a person; you're not speaking to the collective. I imagine I have an imaginary reader in front of me, an ideal reader who is in a good mood and in a mood of understanding, and maybe similar to me in a certain sense. So I address myself to this reader, but it is a sort of symbolic reader, no? I never think in terms of numbers, though, because really it's impossible to understand. When I wrote my book called The Silent Duchess, well, I was sure it was a book that would not appeal to a large audience. But it has been my greatest success. So it's unpredictable. Success is a very strange thing. It can change completely; it can arrive when you least imagine. And luckily it's like that, or else there would be no place for new things, for new talents, for experiments.

MS: In La Seduzione dell'altrove, you describe travel and writing as illnesses, afflictions that have passed from your maternal grandmother to your father, Fosco, and then down to you (see page 30). What is the connection for you between these two "illnesses"?

DM: I say it is an illness, but it's not an illness. I mean, yes, it could be an illness because it makes you restless. And you feel that you want to go, you want to go always—around, looking—to know another side of the world that you don't know. But at the same time, it's very tiring and, you know, you have to change places, languages, hotel rooms, and climates, and sometime it's very tiring. Traveling is a process of knowledge. For me it's that. I travel because I want to know more about the world. Also, it's a way of looking at your own life from far away. Sometimes you need to be detached from what tangles you, you know, everyday life becomes so intense and so demanding that you need to go away. And you look from afar and perhaps see things better. I mean, you see things with wiser eyes; you understand that something in your life that you feel is really terrible, is so aggressive, maybe is not. Maybe we are inventing our obsessions, you know? So, for me, it's therapeutic. Illness and therapy, you have them both, and at the same time, as I say, it is a process of knowledge.

MS: So are there similarities for you between the acts of travel and writing in that both may be a way to see the world, a way to process experience?

DM: Yes. There are many similarities because writing is a voyage. You are traveling through another world. The world is the invention. It could be a historical period that you don't know, that you haven't lived, but that you are trying to understand, you are trying to go through. And through this travel, which is a travel of the mind, at the same time you understand lots of things of today in comparison. When you compare today's life, the current way of living or the current culture, with what existed in the past, you learn a lot of things. If you don't have something to compare with today, you can't understand. You can't understand today if you don't have yesterday, no? And you can't project the future, tomorrow, if you don't know today and yesterday.

MS: You have lectured all over the world—at literary conferences, theater workshops, forums for social justice, and as guest professor and artist in residence. How do you respond to your role as a cultural ambassador?

DM: Well I don't feel like a cultural ambassador! But, well, I feel that I am very attached to my country. I love my country, but I want to be free to regard it with sharp and critical eyes. I think this is also the duty of an intellectual, to be very critical. This doesn't mean that, if you are critical of your country, you don't love your country. Rather, the more you love your country, the more you want the country to function well, so you are critical of the things that don't function. And that's why I try to be informed of what happens in my country and I try to ask what I can do as an intellectual. I try to illuminate, to persuade other people of what could be changed in a country that has possibility, a great country, a country of great people that have done great things, no? And this moment is a moment of crisis—political, ethical, social—and I want to persuade Italians that we can do better. And that is my social work, my social engagement.

MS: In preparation for your visit, I ordered various editions and translations of your books. I notice that the book jacket for Voices, from 1994, describes you as "Italy's most controversial author." Do you see yourself as controversial, as a polemical figure?

DM: Well, after a certain kind of recognition all over the world, I now have become, maybe, more accepted. But for many years, there were lots of critics and aggression. I remember once in a paper, a right-wing paper, there was a photo of me and Pasolini with the caption "Left-Wing Pornographers." I don't know how you can say that our work was pornography! But they wrote this just because we were speaking about sex or, you know, speaking in a way that they didn't like, in a nontraditional way, you see.

Another time, a magazine that was a sort of popular weekly took a poem of mine and made a letter, a false letter, from a prostitute. It said, "I am a prostitute and I know everything about life in the street, but I was astonished and scandalized by the poem of Dacia Maraini!" This, naturally, was not true, because I went there and I said, "Let me know the name of this prostitute because I want to speak with her." And I realized that she didn't exist, that they made it up on purpose for polemical reasons. That was in the 1960s and '70s, but now they don't dare so much.

MS: And why do you think that is?

DM: I'm more powerful. Not "powerful" in the sense of doing something political, but I have the power of prestige. That means when you have prestige in several countries in the world and critics are writing about you, well, it's difficult to attack. You are less fragile, you are less alone, you have something on your shoulder. But that comes, naturally, after years of work. That comes from readers, not from institutions.

MS: Lately, Italy has been in the international press quite a bit, generally for negative reasons—Prime Minister Berlusconi's legal troubles, the degrading representation of women in the media, etc. What do you see as the biggest issues of concern for Italian society right now?

DM: Yes, it's a moment of crisis, certainly, not only economic crisis but psychological, cultural crisis. Because we are stuck, we are not moving, you see. The idea of democracy is that you have a parliament where there is a majority and minority. The majority has to respect the minority; there must be a dialogue, and then things have to be discussed together. Now they don't do it. They count only on the majority and vote for laws that haven't been discussed with the minority, and there is a very personal kind of government in which the personal counts much more than ideas and other people. This, I think, is very bad for democracy.

But at the same time, until now everybody was saying, well, Italy is dormant, they are sleeping, they just accept the status quo, they don't protest, no? Well, I think that's not true because, for example, on February 13—I was there—there was a demonstration of one million people, all around Italy, thirty-two towns invaded by people.* Everybody joined this protest, this public protest. There were no [political] parties, there were no public figures, only people on the road. And I think this is a sign because we haven't had a big demonstration like this since the seventies. I think it's a sign that Italians are starting to be fed up with this way of dealing with politics, and they want to change. . . .

Something that hasn't changed—because we can say that the situations, specifically in Europe and the States and the Occidental world, have changed for women and the laws are very advanced—is violence. Even in the world that is more developed, you will find an amount of violence that is increasing. That is very strange because we thought, in the seventies, for example, that with schools, with wealth, with better circumstances in life, violence would go down. Instead, on the contrary, we see that violence is increasing, specifically violence against women and children. This is a question that I think is a wound to a society. So how to get rid of this violence, how to deal with this violence? Also the imaginary violence, the violence you find in all the films, on television, the violence that you see in newspapers, magazines, in the comics of children. It's violence against the weak. And I think this is the issue, maybe the most important issue of our time.

MS: How do you think we can move away from that as a society?

DM: It's difficult. It's not easy, because it's so strong. It spreads, specifically in the imagination that comes from images. It's all based on violence, on shooting, on killing, on blood spilling everywhere. So I think that the only way is to propose a world that is less violent, to propose a world—but not ideologically because, you know, it's difficult—to propose an alternative. That means a world in which love is more important, personality is more important, character is more important . . . life is more important, relationships between people are more important, etc. It's not easy but that is, I think, a task for intellectuals and those who really are against this kind of world.

March 2011

Dacia Maraini is a well-known Italian writer whose work focuses on women's issues. The author of numerous plays, poetry collections, and novels, she is the recipient of many awards, most recently the Premio Strega for Buio (1999), and in April 2011 she was named a finalist for the fourth Man Booker International Prize. Her plays continue to be translated and performed around the world, and Bagheria (1993), her memoir about growing up in Sicily, stayed on Italy's best-seller lists for two years. Several films have been made from her books, and she has written several screenplays. Maraini continues to be active in feminist causes and as a commentator on politics and society, especially in columns for newspapers and weeklies.