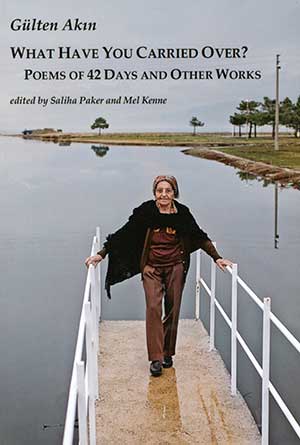

What Have You Carried Over? “Poems of 42 Days” and Other Works by Gülten Akın

Saliha Paker & Mel Kenne, ed. Greenfield, Massachusetts. Talisman House. 2014. ISBN 9781584980964

If you only acquire a single book of world poetry this year, try this one. In 2008 Gülten Akın was voted the “greatest living Turkish poet” by a group of fiction writers, poets, and literary critics. Born, in her own words, “in the tenth year of the modern Turkish republic” (i.e., 1933), she has published twelve major collections, starting when she was only twenty-three years old. Even though there already exists in English a full-length critical study of her work from Indiana University Press by Hilal Sürsal (Voice of Hope, 2008), the current volume is the only selection of her poetry to be published in English.

If you only acquire a single book of world poetry this year, try this one. In 2008 Gülten Akın was voted the “greatest living Turkish poet” by a group of fiction writers, poets, and literary critics. Born, in her own words, “in the tenth year of the modern Turkish republic” (i.e., 1933), she has published twelve major collections, starting when she was only twenty-three years old. Even though there already exists in English a full-length critical study of her work from Indiana University Press by Hilal Sürsal (Voice of Hope, 2008), the current volume is the only selection of her poetry to be published in English.

General editors Saliha Paker and Mel Kenne present an admirable variety of Akın’s poetry, spanning sixty years, and, perhaps equally significantly, provide complete versions of her poems by a host of translators, not just themselves. The question the book’s title asks, “What have you carried over?,” thus serves a double purpose. It alludes to this quiet manifesto that permeates all of Akın’s work—“if love is right there inside you / if you’ve carried it over / . . . / let it go into the snow, the mist, the shadows / let it go, into worn-down dreams / now’s the time for it to slip into infinity.” The question of “what carries over” also loosely translates “translation.” In this book, even without the originals en face, one senses how different translators face up to the lyric impulses these poems express. One suspects that some translators have perhaps smoothed out the jaggedness of Akın’s syntax that other translators are at pains to preserve. Several of Ruth Christie’s lovely lyrics are examples of the former, while Paker, Kenne & Co. produce versions that, one imagines, give a wider range of Akın’s voice(s).

Akın has many voices, from the epigrammatic “A rose tree grows inside every refugee,” or this two-line poem, “—Then I grew old, behold / A sentence as long as a novel,”) to the wryly topical (“oh those revolutionaries / who, mistake after mistake become ever more unmistaken”), to the rich defiance of her early poem “I Cut My Black Black Hair.”

The central work of this selection is “Poems of 42 Days,” a serial poem made, somewhat surprisingly, of thirty-eight, not forty-two parts, and told in many voices, many of mothers coming from across Turkey, from all social strata, responding to the imprisonments and hunger protests of their sons and daughters and the verbal and physical violence of the period from 1978 through the last military coup of 1980. Both in verse and prose, it is outraged, satirical, rapturous, analytical, keening, documentarian. In the end, it is, like Ahkmatova’s, a cry in “the struggle for human dignity.” But it is more, as Akın also explores the odd etiquettes that bind the protesters but also their supporters and their opponents, exposing the “game,” as one of her speakers calls it, of passion/punishment, with its undercurrent of masochism afflicting everyone, and resulting in a startling realization that perhaps “all of [us] are in the wrong.” Maybe the inspiration behind “42 Days” is best summed up, though, in a later 2007 poem: “Here we stand at the messiest point of our time // someone should write us, if we don’t / who will.”

Kurt Heinzelman

University of Texas, Austin