Powerful and Resonant: Native & First Nations Women’s Filmic Presence

We are all painfully aware of the dominant cinematic representations of Native women—the princess, the sexualized maiden, the work drudge (sq**w). Following a hundred years of cinematic tropes, films like Avatar (2009) utilize the Native woman as an exotic accoutrement to the white male hero, an access point into another culture, a way of claiming “Nativeness.” In others, The Searchers (1956), Little Big Man (1970), and Deer Woman (2005), for example, the woman’s symbolic death reinforces and validates America’s ongoing violent and colonial action against Native peoples. It’s a legacy that continues to haunt us all—but one that Native American and First Nations women have taken on full force for one hundred years as actors, independent filmmakers, and producers. The vibrancy of their work resonates with the power and tenacity of Indigenous communities and Native women’s voices.

In front of the camera, Native and First Nations women work within the Hollywood system and outside it, countering these age-old tropes with realistic portrayals of Native women and cultures. Lillian St. Cyr (Winnebago) stands in the heraldic position as the first Native American woman to star in a major film (Cecil B. DeMille’s The Squaw Man, 1914) and to work within the industry against these tropes. Her performance as Nat-U-ritch, the young mother who commits suicide when her son is taken from her, so powerfully portrayed the grief Native peoples suffered under the boarding school and adoption programs that it forced her co-stars to rethink their assumptions about Native people. Such ability to effect change in how we depict and perceive Native women is manifested throughout the industry and characterizes the more contemporary work of actors such as Tantoo Cardinal (Métis), Tamara Podemski (Salteaux), Georgina Lightning (Cree), Sheila Tousey (Menominee, Stockbridge Munsee) Irene Bedard (Inupiat, Cree), Kawennáhere Devery Jacobs (Kahnawake Mohawk), and the late Misty Upham (Blackfeet). Together this small sampling represents over thirty years of experience deconstructing Hollywood’s Indian woman and re-presenting Native women as contemporary, resilient, powerful, and nuanced or complex mothers, sisters, aunties, lovers, and friends.

Equally important and exciting is the ongoing work behind the camera by Native and First Nations directors and producers. We can speak of at least three generations of Native women working as producers and directors since the 1970s. (See the National Museum of the American Indian’s film and media catalog for more on directors and films.) A very brief list includes Alanis Obomsawin (Abenaki), Sandra Sunrising Osawa (Makah), Christine Welsh (Métis), Shirley Cheechoo (Cree), Beverly Singer (Tewa, Navajo), Loretta Todd (Métis, Cree), Shelley Niro (Mohawk), Valerie Red-Horse, Tracey Deer (Mohawk), Missy Whiteman (Arapaho, Kickapoo), Heather Rae (Cherokee), and Tamara Podemski. As they direct and produce documentaries, narrative feature-length films, shorts, and television series, these women take on the process of representing from Indigenous points of view, telling stories from community and cultural perspectives, highlighting the struggles faced by communities, and celebrating Indigenous cultural resilience.

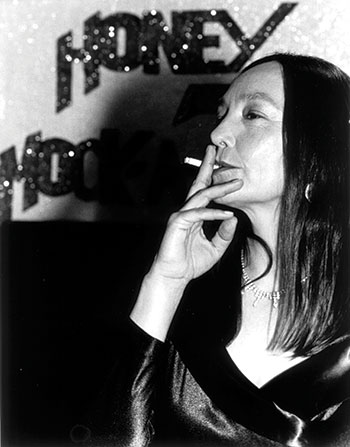

Some of my current favorites across a variety of approaches highlight strong female subjects, a process of bearing witness through film, and the power of Indigenous storytelling in media. They include My Name Is Kahentiosta (dir. Obomsawin, 1995), the sensitive documentary about a resilient Kahnawake woman’s participation in the Oka Crisis of 1990; Honey Moccasin (dir. Niro, 1998), the first Native American detective story that includes original artwork, performance art, and suspense; Older Than America (dir. Lightning, 2008), a powerful contemporary drama about the historical trauma of boarding schools; Fry Bread Babes (dir. Suttle, 2008), a documentary about Native women’s responses to dominant media representations of them; and Magic Wands (dir. Day, 2009), a bilingual (Ojibwe and English) and intergenerational short story about the “magic” of sticks used to harvest wild rice.

My Name Is Kahentiiosta by Alanis Obomsawin, National Film Board of Canada

Augsburg College