Born in 1974 and 1984, Torn in 2004 and 2014: Serhiy Zhadan, Lyubko Deresh, the Orange Revolution, and Euromaidan

This past summer, two Ukrainian writers celebrated milestone birthdays, a decade after the Orange Revolution and amid new upheavals.

Serhiy Zhadan calls himself a “postproletarian punk.” In his novels, he describes the specific circumstances of transition, of life in a society in between the relics of the Soviet past and the search for a new identity. Lyubko Deresh is regarded as the Ukrainian representative of pop culture. His novels are set in today’s Ukraine, but the plots and the characters are global. Zhadan originates from Kharkiv, eastern Ukraine; Deresh is from Lviv in the west. Do they correspond to the cliché of Russophile eastern versus Europhile western Ukrainians?

Which values and attitudes do Zhadan and Deresh adopt? How does the generation born a decade before the collapse of the Soviet Union differ from those born in the period of glasnost, without any conscious experience of the time before Ukraine’s independence? To what extent do these two authors and their work represent their respective generations, regions, and nation? Do they co-construct aspects of a Ukrainian identity, or do they imitate global culture?

Both writers belong to postmodernism, denying the traditional isolationist purpose of Ukrainian literature to stimulate and promote national and social independence. Postmodern literature, especially with the younger writers, is wide open to global influences, dominated by pop culture. It is characterized by its teenage heroes’ use of slang and by topics propagated by the media. The choice of clothes, jewelry, tattoos, or technical accessories as well as musical tastes are part of a new collective awarenness. Those global codes of youth culture function as intertextual references. Being part of the international consumer and entertainment industries, pop fiction still criticizes those very industries by exaggerating an affirmative attitude toward consumption.

While its topics and structures are global, postmodernism in transforming societies differs from postmodernism in affluent countries. One difference is the lack of authority, of father figures: the generation born in the 1980s, called the “post–nineties generation” by Alexander Kratochvil, [1] suffered a loss of role models due to the overthrow of the Soviet Union. In addition, Eastern postmodern literature was dominated by poetry for a significant period, so the preference for prose is a novelty. Combining reality with fantasy or regional and national traditions with global topics is another new fashion.

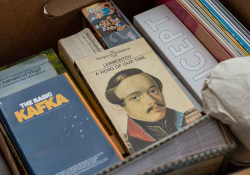

The two authors can serve as examples of these trends: most of their novels are set in their respective home regions—Zhadan’s around Kharkiv, Deresh’s in the Carpathian area—and in the same period: the wild 1990s. Both authors extensively reference pop music like the Doors or Depeche Mode. Minor characters reappear as heroes in subsequent stories or books. In the Best Ukrainian Book contest in 2006, Zhadan placed second for Anarchy in the UKR (2005); Deresh third for Arkhe (2005; Ark). Their novels have been translated into several European languages, but only one into English (Zhadan’s Depesh Mod; Eng. Depeche Mode, 2013).

* * *

Serhiy Zhadan, born in 1974 in the region of Luhansk—today a scene of war—grew up in Kharkiv, where he studied Ukrainian and German philology, defended his dissertation, and taught literature. In his view, Kharkiv remains the intellectual capital of Ukraine, as it was in the 1920s. In the early 1990s, Zhadan became the leading poet of the post-independence generation. He is also a cultural activist who organizes festivals and poetry jams and supports young writers. Still living in Kharkiv, a region dominated by Russian speakers, the fact that he speaks and writes in Ukrainian makes him an exception.

In an interview with the radio station Deutsche Welle, Zhadan stated that he embraced the Euromaidan movement with great enthusiasm and regarded it as the only opportunity to change the country for the better. In his view, the protests demonstrated that society had already changed.

Zhadan, who actively supported the Orange Revolution in 2004, was a member of the coordination council of the Euromaidan Kharkiv in 2013. On March 1, 2014, he was assaulted by pro-Russian protesters and spent four weeks in the hospital. In an interview with the radio station Deutsche Welle, Zhadan stated that he embraced the Euromaidan movement with great enthusiasm and regarded it as the only opportunity to change the country for the better. In his view, the protests demonstrated that society had already changed. He was convinced that the problems in eastern and western Ukraine are the same: common problems, common future, common nation. In contrast to many western Ukrainian authors, Zhadan is not an ideologist but the defender of an active civil society striving for a united Ukraine.

Born ten years later in 1984 in the region of Lviv, Deresh debuted at the age of sixteen. His novel Kul’t (Cult) was first published in the journal Chetver (Thursday) in 2002. Although Pokloninnya yashchirtsi (2000; Worshipping the lizard) was written two years earlier, Kult caused a sensation because of the author’s age and the originality of his style. It became the “cult book” for a new generation. Besides being a writer, Deresh studied economics at the University of Lviv just in case he failed as an author. Deresh did not become a revolutionary fighter but sees himself as a cultural activist. Especially last winter, Deresh felt that he had to defend his position. In a comment posted on his Facebook page on March 4, 2014, he writes: “I was asked why I take a neutral position concerning the current events in Ukraine and if I did not think that I betrayed my country. Dear Ukrainian readers, every one of you has his own notion of patriotism. My fight for Ukraine is the fight for the country to develop culture. . . .” Thus Deresh co-organized the first Ukrainian literature forum in Donetsk this past April, saying in an interview with ZN,UA several days later: “Writers are people who create images. And I believe that Ukraine now needs new images and a new vision for the future.”

Concerning Ukrainian identity, he acknowledges a division of the country—not so much by language or geography but by mentality: Ukrainian identity, in his view, is based on shared cultural values. The examples of Deresh and Zhadan demonstrate that one’s birthplace (eastern or western Ukraine) does not necessarily determine political attitude.

* * *

“Zhadan’s prose is so poetic, his free verse so prosaic.”[2] Zhadan’s language is wild and powerful. The rhythm structuring his endless sentences demonstrates his beginnings as a poet. One sentence in “Forty wagons of Uzbek drugs” (Himn demokratychnoyï molodi, 2006; Hymn of the democratic youth), for example, continues for more than four pages, describing smells in a train. Words cascade in staccato sentences and associations blur as if written in a delirium. The rough, snotty, vulgar and at the same time lyric and proclamatory language sometimes resembles rap, sometimes “verbal jazz.” For his unique style, Zhadan became known as “the Ukrainian Rimbaud.”

Zhadan describes an absurd daily routine between communist past and turbocapitalist present. The author’s melancholy tone is neither nostalgic nor cynical but more of a Gogolesque satire.

Being a witness of the 1990s transition, his novels are set in scenes of industrial wasteland dotted with such relics of the Soviet Union as statues of Lenin. In his novels, the East becomes what it once was: a border region crisscrossed by contemporary nomads evoking the nomads of ancient times, thus creating new geopoetics. This is especially true for the novel Voroshylovhrad (2010), in which Zhadan undermines the image of an ethnic and cultural homogenic nation and drafts an alternative model of Ukraine—the positively connoted literal “border region”—“U kraїna.”

Zhadan’s painful realism is down-to-earth and produces an atmosphere that reflects the disillusionment, hopelessness, and omnipresent lack of prospects. He describes an absurd daily routine between communist past and turbocapitalist present. The author’s melancholy tone is neither nostalgic nor cynical but more of a Gogolesque satire. Zhadan brutally and drastically describes the ruthless and greedy society of the “Wild East.” While he clearly rejects the past as well as the present, he is still a chronist, keeping the collective memory and grappling with the recent past.

The stories he tells are not self-contained but instead open-ended, meandering grotesquely, as if improvised. Stories within the story and associative chains sometimes harshly cut off a storyline. Zhadan’s characters are young, especially odd types. The author does not create complex psychologies. The characters rather represent stereotypes carried to extremes, mostly losers and outsiders, who are permanently drunk and drugged. They provocatively use slang and colloquial speech. Lacking father figures, they are nomads wandering through eastern Ukraine (rarely beyond). His characters are failures, and so are their journeys: one hero fails to deliver a message (Depeche Mode), another fails to find the origins of anarchism (Anarchy in the UKR) or to build up businesses (a gay bar, organ smuggling, or funeral services; Hymn of the Democratic Youth). The credo of failure is described by Zhadan himself: “Any attempt to create something permanent in this life is condemned to fail from the onset; it is like building on rapidly running water—the water washes away your building material and overruns you coldly and indifferently” (Hymn of the Democratic Youth).

While the titles Big Mak (2003), Anarchy in the UKR, and Depeche Mode point to the American lifestyle, Hymn of the Democratic Youth, Voroshylovhrad, and Mesopotamiya (2014; Mesopotamia), Zhadan’s later novels, do not. In contrast to the earlier novels, they establish a new model of geopoetics and national identity as mentioned above. In the finale of Voroshylovgrad, the hero possibly finds a home in the border region: Are the failed journeys and homelessness of Zhadan’s heroes over? Are the latter novels pointing to a new, more optimistic, mature Zhadan?

For his original, independent, and radical voice, critics called Zhadan an anarchist and the enfant terrible of Ukrainian literature. Because of his characters and topics he was often compared to Charles Bukowski, Irvine Welsh, and Viktor Erofeyev.

* * *

Deresh’s work is likewise characterized by a virtuosic use of language, though it makes an easier read compared to Zhadan’s. Sometimes crisply clear, sometimes frantic and erratic, it balances between pathos and irony. Deresh’s novels are set in western Ukraine, mostly in Lviv or the small town of Midniy Buky, where his teenage heroes experience love, rebellion, drugs, and violence against the background of the battle between good and evil: eternal topics, which Deresh fancily combines with the eastern European reality of the 1990s. Teenagers are organized in antagonistic gangs; the so-called hippies and pazany—the latter being criminals—appear in several novels. Accordingly, Deresh’s heroes use the slangs of youth and subcultures. In Worshipping the Lizard, English vocabulary marks the growing influence of global culture while the Soviet past is mocked by an ironic use of the Russian language. The lack of father figures is not as striking as in Zhadan’s novels. Also, Zhadan’s constant theme of journey and failure is missing.

Above all, Deresh’s work stands out for its eclecticism. On the one hand, the wide use of citations and intertextual references picked from American and postcommunist cultures shows his erudition. On the other, his work mixes reality and violence with Ukrainian myths and fiction in an unprecedented manner. He freely recombines references to classics with trash and splatter, school stories with horror. This made Cult a cornerstone and Deresh the wunderkind of his generation.

Everyday life slips to parallel worlds of hallucination or violent rage; storylines take complete twists and turns; conspiracies of evil powers aim to destroy the world. These topics made critics compare Deresh to H. P. Lovecraft, Stephen King, Edgar Allan Poe, Jack Kerouac, or Carlos Castaneda. (They have yet to mention Quentin Tarantino.) Trash, obscenity, and starkness are so exaggerated that some critics accused the author of trying too hard and of being immature.

Deresh’s later novels are more spiritual and philosophical, questioning the meaning of life. Today he thinks that his prose serves to revive personalism and dignity in depersonalized postmodernist literature.

Like Zhadan, Deresh has also evolved. His later novels are more spiritual and philosophical, questioning the meaning of life. Today he thinks that his prose serves to revive personalism and dignity in depersonalized postmodernist literature. For the first time, Deresh clearly expressed his new philosophy in Trokhy pit’my (2007; A bit of darkness): six out of a group of people who decided to commit suicide in the Carpathians are healed by a shamanic ritual and find life’s meaning. Personalism in society, new beginnings, and emotions are the topics of Ostannya lyubov Asury Makharadzha (2013; The last love affair of Asura Maharaja). And in Myrotvorets’ (2013; The peacemaker), Deresh asks moral questions such as, Was Robert Oppenheimer a creator or a destroyer?

But the end of Worshipping the Lizard already signals this evolution: the hippies, who are the good guys, not only avoid responsibility but feel no repentance at all after killing their tormentor. Thus Deresh ridicules moralism, one of the typical elements of popular culture, especially from Hollywood. “Dostoyevsky wrote a whole book about the ordeal of some chuvak-guy who snuffed out an old hag. We killed and felt nothing” (Cult). Are the good still good after committing great evil? might be the central concern of Deresh’s work.

Zhadan and Deresh both transfer global culture to the Ukrainian context not only by picking elements of popular culture but by remixing and reconfiguring them. The process of decoding and recoding is disturbed, resulting in distorted messages.[3] This becomes obvious in two sidelines to the main story of Depeche Mode depicting an absurd clash of cultures: an American preacher’s enthusiastic sermon is translated into Ukrainian beyond recognition, as if translated by an online tool, and a radio program on Depeche Mode not only contorts facts about Dave Gahan and his band but—following the socialist tradition of dismantling Western cultural influences—does not even play their music.

Both Zhadan and Deresh include global values in their fiction yet present them in a national and regional—urban eastern Ukraine and Carpathian village—way. Besides regional and national peculiarities, both authors record the search for a Ukrainian identity. They describe the chaos, the loss of authorities, and the absurdity of everyday Ukrainian life.

Apart from selected common features, the authors widely differ in their views of the world. One reason might be that Zhadan experienced firsthand the collapse of the Soviet Union and the years after—an experience he shares in his novels and expresses by his radical style. Deresh was born a decade later. Even though many of his novels also take place in the early 1990s, he is much more open to mainstream popular culture and entertainment, imitating Western examples rather than just referring to them. In an interview with the Swiss journal NZZ in 2007, the renowned poet Yuriy Andrukhovych said that according to his German publisher, his own books were read by people who are interested in Ukraine, whereas Deresh attracted readers who did not care if he is Ukrainian because he depicts topics that are interesting to all teenagers, regardless which country they come from.

Neither Zhadan nor Deresh can be regarded as representatives of their generations. Their style is too individual. Nevertheless, both have created exceptionally original and groundbreaking work and become pioneers of their respective literary generations.

Bonn, Germany

1 Alexander Kratochvil, Aufbruch & Rückkehr: Ukrainische und tschechische Prosa im Zeichen der Postmoderne (Berlin 2013), 154.

2 Rostislav Mel’nikov and Yuriy Tsaplin, “Northeast of the Southwest: The Contemporary Literature of Kharkiv,” The New Literary Review (2007), 85.

3 Observed by Stefan Simonek, “Westliche Elemente von Pop- und Konsumkultur in der ukrainischen Gegenwartsliteratur (Zur Problematik des Kontextwechsels),” Studi Slavistici X (2013), 205–217.