We Were Born in the Houses of Storytellers

After presenting a sweeping landscape of Arabic poetry since pre-Islamic days—when “poets resembled prophets”—the author offers a reassessment of the late Palestinian master Mahmoud Darwish (1942–2008), with whom he shared a long and deep friendship.

There is some cause for anxiety about the achievement accumulated by the last few generations of modern Arab poets, those dating back to around the middle of the last century. It is an anxiety that can only compound the mass of fears in face of so many losses on the ground—the withering of the social fabric, the erosion of an entire body of rights and truths produced through a long history of coexistence. It is an anxiety that is indeed wholly justified if we look to the facts on the ground and witness the transformations that have taken place, which have shifted a place and a people toward an other geography, an other history, an other culture. These transformations have been accompanied by an uprising called the “Arab Spring” and by the rise of “political Islam,” which includes among its numerous concomitants a discourse relying entirely on a Salafist vocabulary, drawing its proof-texts from a selective history shorn of all context and rendered blind through a violent process of negation and removal that combats the variety and differentiation of life and of daily values.

It is a discourse that emerges from the past and from loss, from the solemnity and silence of the past, from the bitterness and despair of defeat. It draws from this alone to produce its force and its power to convince and militarize.

It is a discourse that places the burden of the present and its losses squarely on the back of the “other,” the one who is different, a figure who hides around the corner setting his trap on our way home, defiling our pure garden and sending the children away from their family’s home.

A discourse that does not love poetry and does not trust poets.

This terror has left its mark on the poetry scene, whether in the summoning of ready-made methods from the past, or in the drawing of inspiration from the concepts of this discourse—its problems, language, and values—in what amounts to a “revival” movement that is wholly its opposite.

Or it manifests in a withdrawal from poetry in an extension of the Salafist idea, which looks on poetry with great fear and doubt. It sees in poetry no instrument for the preservation of sacred texts to be accepted or glorified. Here I make reference to the categories embedded in a religious idea that embraces the casting of doubt on poetry and poets, an idea that accompanied the first stages of the Islamic “Call,” when Islam in its early historical phases confronted the threat of poetry to the “miracle of the Qur’an” and its aesthetics and actively denied the description of the prophet as “poet.”

This was in an age when the Arabs were greatly concerned with the competition between poems and poets in the annual markets organized by the tribes, to which warriors would arrive on horseback to display their talents, when merchants and poets would recite the poems they had spent the entire year composing and perfecting in close contact with trusted critics. The finest poem would then be hung on the wall within the Kaaba, in view of statues of the pagan gods of the Kaaba, within the house built by the grandfather of the Arabs, Abraham, and their father, Ishmael—the most sacred place to the Arab tribes both before and after the coming of Islam.

“Poetry” moved in the shadow of sacredness and touched it with strength, and the poets resembled prophets.

Those were the first wars in which the “Call of Islam” pitted itself against poetry and was occupied with the renunciation of the poets—all this notwithstanding the marginal exceptions that allowed poets to exist within a defined category, and despite the transformations that came about after Islam arrived to become an incipient state power, once the conquests had arrived to the great metropolises of Syria and Iraq.

Exile has gradually become the center of culture, while at the true center the experiments have become isolated and withdrawn from view.

It is precisely that war which is taken up by the Salafist discourse that now circulates in the region, a war that is invisible but violent, armed, and sacred, which contributes to a real decline in taste that can be felt through the popular embracing of the Salafist discourse, through the clear decline in the influence of the achievement put forward by the Arab generation of the 1980s, among whom were the Palestinian poets. This is not to claim a lack of important experiments among the younger poets, which are indeed numerous and diverse. But they take shape, for the most part, as trends in an exile which has become the center. Exile has gradually become the center of culture, while at the true center the experiments have become isolated and withdrawn from view.

Some poets, and in particular those of the younger generation, withdraw often before they have reached maturity. On the one hand this ensures them a ready-made audience, and on the other hand it excuses them from having to enter into the enterprise of writing itself. Here we can speak of “claimants” to poetry rather than of poets.

Thus to invoke a poet such as Mahmoud Darwish and to reread him in light of the present appears as both an attempt at a definition of the Arab poetic achievement and a defense of it at the same time.

•

“We are exiled on our road to exile, and it is in light of this that I continue to write.” This is what I thought as I saw my mother standing on the ruins of her village, Zakariyya, after a cruel absence of a half-century. She stood there before the shrine of the prophet Zechariah in the company of three of her sisters. They were four widows in black shawls who had that morning reached the square of the village Zakariyya, which took its name from the obscure shrine of the prophet Zechariah. I grasped hold of an image of that scene and would later write a short poem with a simple name, “Four Sisters from Zakariyya,” which was translated by the Iraqi poet Sargon Boulus and the Palestinian poet Fady Joudah into English.

This story took place at a time when I was engaged in a conversation of several long weeks with Mahmoud Darwish, in a coffee shop on one of the hills of Ramallah, concerning our definition of “the enemy.”

On the way back, my mother asked me if the American Jewish journalist who took us in her private car—this girl who looks like an Arab, she said—might know the fate of “Rivka.” I had staged a small deception—Usnat Tarabulsi was not a journalist and was not American, but was rather an Israeli film director and my friend, and her car was the only means we had of ensuring my mother’s safe arrival back to the village.

That was the first time in fifty years that she had pronounced the name “Rivka,” the first entrance into her many stories of her Jewish friend she had known throughout her childhood and adolescence in the village, before the forced migration and Nakba. Suddenly, a slender Jewish girl appeared, with black hair and Arab eyes, and began to breathe and walk in her memory. It was as if she, the Jewish girl, simple in her adolescence and her walk, awoke from a long absence of half a century to join those who continued to move in the family house, those whom my mother, the true narrator, granted the rights of life and breath in her memory.

“Rivka” arrived late, but she found her place preserved, untouched by “occupation,” never replanted or farmed by others. She found her narrative just as she had left it. The stance on the ruins of the village Zakariyya, which derived its new name from the original “Caper Zacharia,” seemed like a key: it was as if she, my mother, had without intention shifted some secret icon on the locked wall and permitted passage to the young Jewish woman.

This is just what Mahmoud Darwish was doing in his early poems “Between Rita and My Eyes Is a Rifle,” “A Soldier Dreams of White Tulips,” and “Record: I Am an Arab” and then later in “When He Goes Distant” and “Final Scenario.”

My mother’s own Rita, by the name of Rivka, came out and began to wave to her light-skinned Arab friend from the edge of the forest cover, from where she could see the small train station in the valley that reached between Jerusalem and al-Ludd.

I said to Mahmoud: “Yesterday my mother offered two confessions before doing the evening prayer: that she has a Jewish friend whom she misses, and that ‘they’ are better than us at farming.”

Sirriyya Mashal is my mother’s name, which I believe is a Turkish name and is still frequent even a century after the end of the Ottoman occupation of Palestine. She entered into the long conversation between Darwish and myself by making these two brief remarks before rising for the evening prayer, before she decided to return to her home in Amman on the east bank of the Jordan River, because she also did not want to be a refugee in Ramallah, and because the entire country would be a place of exile after leaving her home in Zakariyya.

When she left this place of proposed exile and returned to her own exile, she had added a new and prominent personality to her stories: “Rivka.” She was very concerned with her fate. It seemed she had decided in some final way to open this closed door in her narrative.

“Why did you leave the country?” I asked her.

“We were afraid; they were killing people and burning villages,” says Sirriyya Mashal.

•

There is something resembling a dichotomy here. On the ground and in the popular “imagination” fed by daily needs and goals, the “other” moves and speaks his own language, calls out in his own personal name—the other who becomes “work supervisor,” “group merchant,” and “factory owner”; “shooter,” “occupier,” “racist,” and “pious man praying for defeat of the Arabs.” But in the written text he returns to his “collectivity,” to his obscurity.

Quotidian life, with all its cruelty under the conditions of occupation, has been able to unravel the enemy / the other and transform him into numerous others, to grant to him in his minor details diverse qualities, to delineate him and give him nuance without excusing him for the basic condition under which “relationship” has come about, the occupation. It adds to this basis numerous and various qualities that humanize him completely. Yet the enemy still moves in the written text within his locked form.

•

Thus, in this forbidden space between consciousness of the quotidian and consciousness of the written text with its “high” classical language, Darwish’s project took shape, posing a central challenge to the conditions of the political in Palestinian and Arabic poetry.

That was clear at every stage of his achievement, including the beginning stage, which was so connected to resistance and pervaded by ideology. It is the geography of those early works and their angle of approach, the clear tone and fresh diction with which they address the enemy / the other through bodily encounter, that gives them prominence and relevance down to the present.

At later stages, Mahmoud goes further in his project and annexes forbidden fields of meaning, benefiting from his prominence within the collective Arab and Palestinian consciousness, and his special knowledge of the culture of the other through his daily friction within a living society. Beneath the veil of the page stands also his existential anxiety. He extends the events of his narrative with a mix of the transcendent and the material. In those texts Mahmoud presents his identity with strength and clarity, but while doing so leads the “enemy” out of his collectivity and brings him out as an individual, as if uncovering cracks in a wall. His new texts overwhelmed the Arab taste—for example, “Rita” or “A Soldier Dreams of White Tulips,” a dialogue with an Israeli soldier that appears in one of his early collections. The conversation is simple and painful, free entirely from any attempt to wash the soldier clean of the blood of his victims. The conversation moves on two levels, reality and dream. In reality the killings are accounted for with medals granted. “I killed many but they gave me only one medal,” says the “obedient” soldier, addressing the poet simply by his name, “Mr. Mahmoud.” But without leaving this reality behind, the soldier is able to dream. In one move the enemy is made human and returned to the quotidian, while at the same time Arab taste is permitted to accept an enemy that at once possesses a ramified human nature while also firing his gun.

“Between Rita and My Eyes Is a Rifle” was transformed by the Lebanese musician Marcel Khalife into a sweet and plaintive love song. Despite the fact that this love song was born during the brutal Lebanese civil war of the 1970s and in connection to the PLO, one of the parties in that conflict, nevertheless the song enjoyed a truly strange fate, being transformed into an icon of the Arab left, which it has remained down to this day.

The story of forbidden love—between the Jewish girl, the beautiful woman soldier Rita, and the Palestinian poet—far exceeded the destiny planned for it. Those who love the song continue to be affected by it while, as if in tacit agreement, declining to notice the identity of the girl.

Even in early texts such as “Record: I Am an Arab,” Darwish was able to present an image of the victorious enemy who is unable to overcome identity. No image of “the victorious enemy” existed previously in Palestinian or Arabic texts with anything like the clarity that he was able to put forward. Even later, as the “victories” of the enemy constantly accumulated, modern Palestinian poetry continued to speak of an enemy without real characteristics, with no bodily presence, no shadow: an enemy who is dead, yet who continues to amass victories outside the poem.

One could speak here of a loss that gives rise to a ghost possessing the rank of “enemy.”

Darwish approached his “enemy” directly, unraveled him, granted him character traits. The clarity of the enemy reflects the clarity of the one in resistance, grants to the struggle a missed dimension of reality. This realism is necessary for the construction of dialogue and for the movement toward undiscovered regions, but by means of a human body possessing two seeing eyes. It will grant vision to the enemy, it will follow him and observe him. At the same time it will grant the transformation of the poet, here Darwish, into a “Trojan poet.” This is what Darwish did and what Sirriyya Mashal, my mother, did, when she opened the door after a half-century of mutual negation to liberate Rivka from her obscure and locked form as “enemy” and beckon her to enter and pursue her memories.

•

It is easy to defeat a ghost, to burden it with the causes and excuses of loss, to achieve a desired heroism through ignorance and exaggeration. But it is difficult, to the extent it is realistic, to confront an “enemy” who contains contradictions and human tendencies with all their attendant implications. Here, knowledge and culture must structure a text from the inside and take the place of the prevailing rhetoric, which conceals its inadequacies and failures behind the confusion of language.

The attempt to force the absence of the other / the enemy is an attempt to sacrifice knowledge. It is epistemological suicide by political means. The enemy is a part of our culture and our sources; he is among the necessary contents of identity and among the sources of exile also; he exists strongly despite the instruments of ignorance. He is brought to existence in the struggle, in defeats, in losses and resistance. He is the main instrument through which the culture of absolutism grows up and is equipped for the extension of control over the people.

By summoning him—and this is absolutely necessary—we are able to extend the reading of our existence in the light of resistance. Struggle grants us both confidence and spite at the same time, it takes and grants, it uncovers regions of weakness and lands of strength, and it reveals gaps in the wall. We do not remain ourselves after every round—we must see what we have become, and this will not come about except through a deepening knowledge of the other.

The other / the enemy is an inborn extension of what is silenced in our culture, in religion, power, and sex.

There were novelties at every stage of Darwish’s project, additions dependent on a different knowledge and different culture, perhaps the most important element of which was his knowledge of the “other” and his distinct drive to create a conversation and to then deepen this conversation and to convert it to new positions. Thus he left behind the simple romantic scenes of “The Soldier Dreams of White Tulips” or “Between Rita and My Eyes Is a Rifle” for the scene of the “enemy” in his poem “When He Goes Distant” included in his striking collection Why Did You Leave the Horse Alone? This conversation brings him all the way to his late poem “Ready Scenario,” which leaves its conclusions open for another poet to pursue the scene, the scene of murderer and murdered suspended in one pit.

Diametrically opposite and parallel to this was his opening of internal conversation based on contemplative questions rather than the pursuit of answers, alongside his contemporary Edward Said. Thus Darwish chose the title “Counterpoint” for his poem, which is a translation of the term made current by Said, and chose the idea of a bridge for the structure of the poem, with all its open polysemiocity and venerated classicism.

There is something here that draws many to manufacture a comparison between Darwish and Israeli poets like Bialik (whom I do not know how far it is accurate to consider as Israeli) and, in particular, the Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai, for whom Darwish did not conceal his admiration on numerous occasions. This comparison is attractive to some due to an external and simple understanding of the political narrative told by politicians on both sides. Both poets at some stage embodied the national identity of their peoples and defended and supplemented the prevailing narrative. For my part this comparison seems rooted in the period of the 1970s, when Israel came forth after the Six-Day War as a victorious nation cloaked in legends of triumph but did not give up its monopoly on the role of the “victim,” just as the Palestinian national movement rose and cohered in isolation from the advice of the Arab political regime. In a paradoxical way, defeat allowed Palestinian identity to part ways with the grip of the Arab regime. And this identity contributed to its reformulation and preservation, resurrected it in a framework of the “revolution of exiles” to which the Palestinian exiles contributed, at the forefront of whom, no doubt, were Edward Said and Mahmoud Darwish.

But after the publication of his striking book Why Did You Leave the Horse Alone?, Darwish went beyond the comparison with Amichai and Bialik. He turned to go down his own road, a road he then paved with the collections It Is a Song and Less a Flower, and further deepened throughout the 1990s and up to his death in Houston in 2008.

That collection, Why Did You Leave the Horse Alone?, seemed something like a return in the light of new wisdom. He chose the characters that he had begun with in the 1960s—the grandfather, the mother, and the enemy in particular—but they arrived to new structurings, new ideas of greater serenity and wisdom.

This brings me to the end of summer 2007, when Mahmoud Darwish was an honored guest at the Struga Poetry Evenings in Macedonia, the oldest and most ancient poetry festival in the world. It was the final poetry festival in which he would participate, other than one evening in France on his way to Houston. In Struga, they love to recall that he visited them in that final summer, when the festival granted him its rich prize, the Golden Crown, granted annually to one influential world poet.

It is a custom of the prize to plant a tree for the bearer of the crown in the Garden of Poets, alongside a bronze plaque bearing the name of the poet and the date of his reception of the prize. In the garden are fifty towering trees bearing the names of poets from Pablo Neruda of Chile to Bei Dao of China, the American Ginsberg to the Israeli Amichai, the Syrian Adonis, the Russian Yevtushenko, and the Swedish Tranströmer.

At the press conference following the garden reception, according to the Macedonian poet and translator Nikola Madzirov, one journalist asked Mahmoud Darwish: “How do you feel having your tree planted so close to a tree bearing the name of the Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai?”

Mahmoud answered: “It does not bother me. A tree will not kill a tree.”

I have heard this story several times and in several different forms from different persons. Madzirov was a direct witness to the story, which later became a common anecdote. All the versions preserve the same decisive ending: a tree will not kill a tree.

If I had to find a comparable poet of “exile” concerned similarly with the deep questions of identity, I would no doubt choose Paul Celan.

Ramallah

Translation from the Arabic

By Sam Wilder

For Further Reading

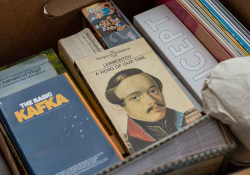

Mahmoud Darwish

Mahmoud Darwish

Memory for Forgetfulness: August, Beirut, 1982

Trans. Ibrahim Muhawi

University of California Press, 2013

Mahmoud Darwish

Mahmoud Darwish

Unfortunately, It Was Paradise: Selected Poems

Ed. & trans. Munir Akash & Carolyn Forché

University of California Press, 2013

Mahmoud Darwish

Mahmoud Darwish

Why Did You Leave the Horse Alone?

Trans. Jeffrey Sacks

Archipelago Books, 2006

Khaled Mattawa

Khaled Mattawa

Mahmoud Darwish: The Poet’s Art and His Nation

Syracuse University Press, 2014

Najat Rahman

Najat Rahman

In the Wake of the Poetic: Palestinian Artists After Darwish

Syracuse University Press, 2015 (reviewed on page 93)