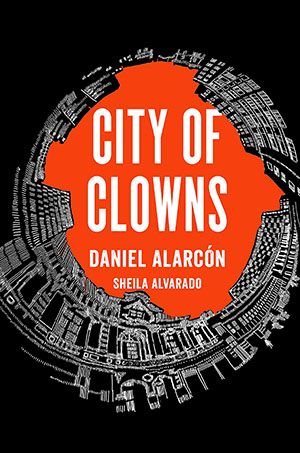

City of Clowns by Daniel Alarcón

Illus. Sheila Alvarado. New York. Riverhead Books. 2015. 138 pages.

Illus. Sheila Alvarado. New York. Riverhead Books. 2015. 138 pages.

Spotlighted already in 2010 as one of the New Yorker’s “20 under 40,” Peru-born and Alabama-raised Daniel Alarcón pounds out fiction with the laser-like acuity of an investigative journalist and with an eye and ear for capturing the kinesis of consciousness of all walks of life in the Latin Americas. We get this and more with the publication of his short story “City of Clowns” as a graphic novel. (The story first appeared in the New Yorker in 2003 and later appeared in his collection War By Candelight in 2005.) Alarcón’s subtle yet penetrating prose coupled with the exquisite artistic talent of Peruvian Sheila Alvarado immerse us in the dangerous deep end of a contemporary Lima, Peru, laden with economic and political misery.

As is characteristic of Alarcón’s south-of-the-border set fiction, he, along with Alvarado’s black-and-white renderings, firmly plants us in the thoughts, feelings, and actions of an ordinary protagonist, Oscar “Chico” Uribe. His father, Don Hugo, is a handyman—and womanizer: Lima was “the place where he could become the person he’d always imagined himself to be. . . . To drink and smoke, to fight, fuck, and steal.” His mother’s nostalgia for a life lived in the countryside and nonstop work as a maid to los ricos blind her to the father’s ways.

As the story unfolds, we learn that it’s not so much superheroic accomplishments that Alarcón and Alvarado are interested in conveying but rather Chico’s constant struggle to not slip into his father’s ways as thief and womanizer; in a remarkable turn of events, one of the mother’s rich clients, the Azcárte family, offers Chico a scholarship that opens doors for him to earn a living with his brain and words as a journalist. But this is not what interests Alvarado and Alarcón. Rather, the visual and verbal narrative combine to show his slide into patterns of behavior he so abhors in his father. Indeed, even though he earns a good living as a journalist, he teams up with a band of marauding clowns to plunder purses and wallets of workers riding city buses. As a clown, Chico enjoys his anonymity—as one of the “ghosts in the multitude.” He quickly finds solace among those who seek out dangerous thrills.

Alvarado’s detailed illustrations intensify Chico’s rapid swirl toward the vortex of the inevitable: the repetition of his largely absent and now-deceased father’s rapscallion ways. Her fine art, detailed black-and-white visuals, move us seamlessly between Chico’s experiences in the present and past. The fluid artistic layout (as opposed to a rigid comic-book panel grid) beautifully allows for an ebb-and-flow narrative movement that slows, pauses, and speeds our experience of Chico in a bustling Lima. Her precise use of light, dark, and shadows makes the representation of the city of Lima so strong that the megalopolis itself becomes a kind of monstrous character. The art illuminates the text, creating an art-prose chiasmatic interchange that ultimately conveys Chico’s deep loneliness, within a space filled to the brim with life that teeters at the edge of a precipice threatening a vertiginous drop into nothingness.

Frederick Aldama

Ohio State University