The American Nobel: Oklahoma’s Neustadt Prize

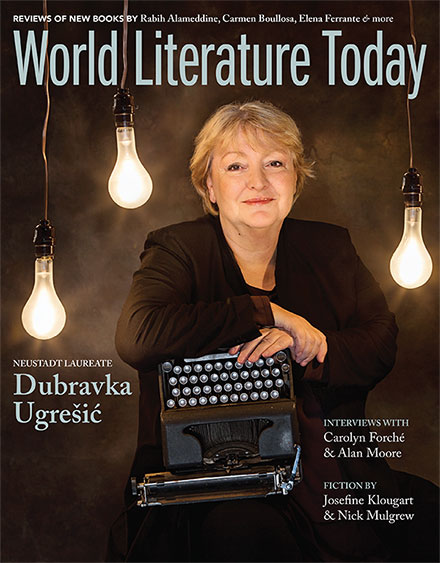

If I had been pressed on what I knew about the Neustadt Prize before going to Oklahoma in November, I probably would’ve said something along the lines that it’s the “American Nobel,” that the prize money is substantial, that it’s held at the University of Oklahoma because of World Literature Today, and that the first author ever published by Open Letter Books—Dubravka Ugrešić—was this year’s recipient. There’s a reason the Neustadt has been labeled as the “greatest literary prize you haven’t heard of,” though—all of which was on display in Norman, Oklahoma, in the week before Halloween.

Founded in 1970 as the Books Abroad International Prize for Literature (it assumed its much shorter moniker in 1976), the Neustadt is awarded every other year to a poet, novelist, or playwright from anywhere in the world on the basis of “literary merit” alone. On the off years, two things happen: the jury for the next prize releases the names of their finalists and chooses a winner, and the NSK Neustadt Prize for Children’s Literature—funded and administered by three Neustadt sisters, Nancy, Susan, and Kathy—is awarded and celebrated.

What most got to me was the care that went into making sure this award has a deep impact on readers and students.

From the best I can tell, the “American Nobel” nickname comes from the fact that over its forty-five-year history, thirty-two of the winners, jurors, and finalists have gone on to win the Nobel Prize, including Gabriel García Márquez (winner, 1972), Czesław Miłosz (winner, 1978), Tomas Tranströmer (winner, 1990), Mario Vargas Llosa (juror), Derek Walcott (juror), Doris Lessing (finalist), and Svetlana Alexievich (finalist).

That’s a pretty fantastic list of authors, and the actual prize—a $50,000 check and a very weighty feather made of silver, housed in a handcrafted wooden box—is equally impressive. But what most got to me was the care that went into making sure this award has a deep impact on readers and students. One of the reasons behind the two-year cycle for this award—announced one year, with the festival taking place in the ensuing one—is so that students can take a class on the winning author and participate in the festival itself.

The idea of taking a “Neustadt Winner” class and being able to meet an internationally renowned author might not seem all that impressive to many of the people reading this, who live in metropolises and are part of the book industry, but for the people of Norman, a tiny little blue bubble in a redder than red state, this is a pretty powerful opportunity.

As one would expect, a number of the festival events are pretty standard: an opening-night reception (which I spoke at, as the publisher of five books by Dubravka dating back thirteen years), a keynote address (“A Girl in Litland,” which appears in the current issue of World Literature Today), an insightful roundtable on her works, and a swank closing ceremony at the natural history museum where Dubravka was given her check and silver feather.

But along the way, there were some interesting detours. A roundtable discussion about the European refugee crisis. (Although not a refugee per se, Dubravka has been living in exile ever since Yugoslavia split along nationalist lines and she became a “Croatian.”) A slapsticky, raucous staging of her short story “Who Am I?” by students from the University of Oklahoma School of Drama. And a chance for the students in the Neustadt class to apply all their book learning and interview the author in person.

•

Before going on, I want to take a moment to say that you should absolutely read Dubravka’s books. If this were a different sort of essay, I’d get all personal journal about our fifteen-year friendship, the first time I discovered her (in an interview in Bomb), about how much she’s meant to Open Letter (our one and only National Book Critics Circle Award finalist!), and the emotional reaction I had when I was referenced in her acceptance speech.

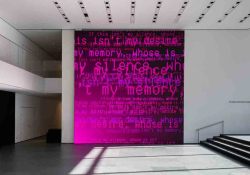

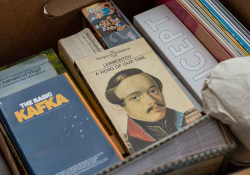

But fuck all that. If you want postmodern playful fiction (Baba Yaga Laid an Egg, “Steffie Cvek in the Jaws of Life” from Lend Me Your Character), if you want harsh and funny truths about the publishing world—like the fact that the New York Times Bestseller List is basically capitalism’s version of Soviet realism, which is both true and a great burn—and digs at agents, editors, bookstores, and the like (Thank You for Not Reading), or witty insight into life in contemporary Europe as an exile without a country (Europe in Sepia), or a pointed response to our “karaoke culture” that values the imitation over the truly creative (Karaoke Culture), or a truly contemporary classic that out-Sebalds Sebald and will be studied a hundred years from now (Museum of Unconditional Surrender), you must read Dubravka Ugrešić. When the history of early twenty-first-century literature—real literature, lasting literature, not yesterday’s latest fad—is written, she will reign supreme.

Neustadt juror—and famous translator—Alison Anderson had this to say about nominating Ugrešić for the prize: “As someone who voluntarily went into exile, she describes the shared experience of solitude with her stories of refugees. She covers injustice, corruption and everything that’s wrong in the world, but in a quiet way.”

The way in which Dubravka’s voice sucks you in with its straightforward observations that seem almost obvious on the surface—who doesn’t hate the tyranny of the minibar?—before taking a sharp turn, slicing into a truth about modern life that leaves the reader both enthused and a bit uneasy about the world in which we live.

•

Following the glorious, well-received performance of “Who Am I?”—a surreal story that draws from a number of works of fairy tale-esque literature, such as Alice in Wonderland—a number of students on campus (see list below) had the opportunity to interview Dubravka. Subjects varied from feminism to how she became a writer to specifics about her works to fairy tales. Since this is the perfect moment to make a bad segue about the Neustadt Festival being like a fairy tale, I figure I should focus on that part. So here are a few quotes from the official class interview:

You mentioned the word “fairy tale.” Why do fairy tales figure so prominently in so many of your writings?

First of all, because I think that fairy tales are a wonderful genre. And I think that they are neglected somehow because they’re an enormous source of knowledge. Not only of language, which is perfect, not only storytelling, which is perfect, not only that they’re a big machine for the production of hopes and images—they are full of psychoanalysis and our first knowledge about the world. And all the symbols you get from the fairy tales. If you’re a careful reader, you can read or project or see into the world that will surround you when you are an adult too; so, first and foremost, there is this absolutely fantastic knowledge that also contains mythology—fairy tales and myths.

Do you have a favorite fairy tale?

I like traditional, older fairy tales. I like folk fairy tales, not written ones. Russian fairy tales are the biggest source. They are actually beautiful. And then [laughs], this is my discovery too, one of the oldest literary genres is, from the gender point of view, also one of the most emancipatory. Because women in fairy tales are smart, okay? They are the winner. They go through this metamorphosis, saying, “These stupid fools!” I encountered an old Bulgarian fairy tale where the hero is a girl. First of all, she falls in love with a dragon. And then she passes through all these phases because she is transformed into a boy, then into a girl, so in the end she has to decide who she is. It’s an extremely modern story for a folktale. And besides, she doesn’t like humans. She thinks that the dragon guy is the best choice. So it’s interesting and liberating somehow. If you carefully read those fairy tales and if you like them, they will teach you. Too, my favorite writers always use this source. . . . Babel, the Russian writer, is a genius, genius.

And Dubravka Ugrešić is a genius. As is the Neustadt family and everyone involved with this festival and prize. Everyone who’s bringing great international literature to Norman, Oklahoma—a city that has made itself into a hub for appreciating great writing in a deep, thoughtful way. This isn’t a prize like most that’s announced and forgotten. Instead, they’ve built a prize that helps change the way students approach the very idea of literature—and that’s the point of it all, right?

Editorial note: Reprinted by permission of the author—an earlier version of this essay appeared on LitHub (lithub.com, November 10, 2016). The students in the Neustadt class, taught by Dr. Emily Johnson, included Hannah-Grace Lanneau, Katherine Bernhardt, Sydney Wynn, Christina Ramirez Billicana-Fierro, Andrea Rivera, Melissa Wilson, Jill Amos, Maria Deal, Gillian Wall, Julius Bitarbeho, Stephanie Eyocko, Laurel Wheeler, Veerle Tierens, Panagiotis Skavaras, Rebecca Maldonado, and Hannah Zinn.