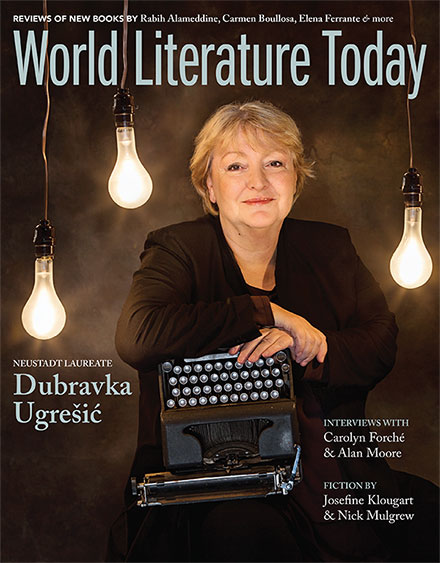

Of Darkness (two excerpts)

Of Darkness is a book about love and death. These seem to me to be the only things worth writing about. When you write about love and death, the beauty in this world’s fabric of small and ostensibly insignificant details reveals itself. Apples petrifying in fruit bowls in the homes of the grieving, the deterioration of our bodies and ideas, the things we believed in and must later discard. Writing is a kind of activism. You create a new language within the language, and once in a while you succeed in making the world deeper and bigger. It’s a way of cheating death. Not to escape the anxiety and the grief but to find access to more life, looking through a new lens of the mind. Writing refracts the light for us in new ways. The light falls on a person’s face as it falls on water. What does it mean to remember something? What is the status of memory? Everything is language. Even nature organizes itself in that way, connecting with us in a language we sometimes feel we understand. We see a grammar in nature. We are nature ourselves.

Of Darkness is about these languages. It is a love story and an investigation of what it means to lose something you love and something you are. – Josefine Klougart

It snowed, and the island became frozen into a sea that joined it to the mainland for months.

She told no one, but walked out into the white that lit up the woods from below.

The cover of snow speaks to the sky, as if together they possess some knowledge they continue to share, in that way to remain as one. A language requiring no translation, like a hedgerow connecting two places in the world.

The cover of snow speaks to the sky, as if together they possess some knowledge they continue to share, in that way to remain as one. A language requiring no translation, like a hedgerow connecting two places in the world.

January. Bells of frost beneath the horses’ hooves, compact snow wedged to the iron shoe, the frog of the hoof blued and fraying in the freeze.

High walls balanced on the branches here.

It snowed, the way it had snowed for days, weeks soon.

Feet kicking up their fans of powdery snow with each step.

The darkness unrevealing of such detonations of crystal.

The crystal shares much with literature. Material held together in a particular pattern,

determined by particular rules. Structures repeating everywhere.

He can see that, he says. It makes sense.

She remembers the snow consumed her tracks and that she was unable to find her way home again.

Trudging, then to pause and listen to the sound of her breath, which in turn startled her. No way forward, no way back.

Like a year suddenly past. Or just a summer.

She remembers she gave up and thought of a farewell scene, a parting from her family and lover. She recalls being surprised at who turned up in her mind.

How many were present, and the way the snow settled in her hair.

•

She visits him again, for the first time in a while. They talk about that. He rocks gently, backward and forward in the chair. He’s a good friend, she thinks to herself. He says he feels no need to fall in love again, that it is past now. After her, love is past. When he goes to the kitchen to get two oranges and some chocolate for their trip into the hills—before they realized they had no time to go to the hills, not that day—she noses around in his living room. The room is so very old. It’s the first time she’s been to see him. She passes her fingers across the spines of some books, the frame containing a photograph he took, and notices a bowl of withered fruit. Three peaches and an apple, their shriveled skins like dulled and sunken cheeks. She thinks it to be the saddest thing she has ever seen. Fruit, sapless and diminished, consigned to bowls of oblivion in the homes of abandoned people everywhere, broken people who yearn as yet, and who will continue to yearn in time to come, perhaps even forever—there, in such places, fruit is left, to decompose and slowly rot, though never quite to vanish. And there it remains, an organic timepiece measuring the hours from the first wrench of grief, when all things came to an end. It’s as if these people wish to be reminded that everything has broken and come to a standstill; or else that life goes on, albeit without them. And they themselves: the advanced age of the fruit becomes that of the body, its deterioration a correlate of their own organism. The grieving body and the dying fruit. The dying body’s celebration of grief. Love becoming solicitude and a diligence as to decay.

Another friend’s oranges, a Cox apple.

The mattress is on the bare floor, everything looks like it’s fallen down; books piled all over, a tabletop deposited without its legs, the shelving just five more or less horizontal lines between uneven rows of books. The sloping walls of the room cast shadows; the busy blade of the scissors. It’s morning. Like the feathers of a wing, the books lean first one way then the other. Plants with their pots broken open like petals scattered on the floor, the white roots extending their pale and sleepy capillaries, soil spread about a core; like her heart, the core of her warmth and the occasional sounds that issue out into the room that encloses her body.

Her body, pumping warmth out into the room. It must be morning. You can tell from the light—soft, the way a body can be soft, an organic, fleshy light that does not stream into the room but barges its way in, breaking things in its path, denting the thin partition walls, pressing the duvet flat as a frightened dog that cowers on the ground; the changing nature of the seams, from plunging indentations to these looser threads that strive toward the cotton like shallow water thrusting onto shore in windy weather, a shimmer of undulation in all things. She turns her head, though strenuously in the light, as if the light occupied the room like some thick transparent gel obstructing every movement. The pillow retains the imprint of his head, the duvet cast aside, its corner turned down like the page of a book. As if to remind of something other than how far one has come, something more important that one (again) wishes to prevent oneself from forgetting, dismissing (once again) from the mind.

She mumbles a few words to herself. Her voice acts like everything else in the room: falling, then falling silent. His body, no longer there. Imprints of the human body are in some way more human than human bodies themselves. They contain the body as a negative, yet something more besides. A very fundamental voice, the tone of the human, that lingers, reverberating in the impression.

One might also consider that time changes everything; that the next day will always be new; that in a way it’s too late to learn what you had to lose after you’ve already lost it—the glancing back over your shoulder, or the longer looks, measure out the ground covered in units of assumptions and kilometers.

There’s something satisfying about hearing a pop song’s reiteration of a simple truth, for instance the banality of not knowing what you’ve got until it’s gone. You lose someone but at the same time gain a more complete picture of the love you nonetheless felt for that person. That’s one way of putting it. But one might also consider that time changes everything; that the next day will always be new; that in a way it’s too late to learn what you had to lose after you’ve already lost it—the glancing back over your shoulder, or the longer look, reveals the land you’ve covered to be different from the land in which you lived. The fields you left behind, the distance measured out in units of assumptions and kilometers. She stands with her hands on her midriff, concentrating on listening. But the light has the same effect as water, distorting all sounds. And yet she is certain, he is downstairs shaving with the electric shaver. The door is closed, she lies down and turns on her side. Lying there on the bed she can look down between the beams and see the door, which indeed is closed.

She gets to her feet. The pane is steamed up, a drop of condensation travels down the middle.

The sky is not blue but white; the light is the voice of the sun, unready as yet, though sleep-drenched it muscles in. The pane is soaking wet. She descends the loft ladder and cautiously opens the door of the bathroom.

He is facing away, quite apathetic.

She goes toward him. In the washbasin in front of him the electric shaver buzzes. He is standing quite still, staring out through the milk of punctured double glazing above the washbasin. She steps up slowly and pauses a few centimeters behind his back. He is naked. She turns her head, as if the light should take her photograph in silhouette, baring her cheek and glancing at her reflection in the mirror that is affixed to the wall next to the washbasin and which cunningly doubles the bathroom’s size. Her face is partially obliterated. Only the part of it that is turned toward the light exists, the rest has collapsed, to dribble like thick glue from her hip, the eye left behind at the shoulder. She blinks, but only the left eye closes, the skin that surrounds the other, at her shoulder, contracts as if in resignation, a half-hearted smile. Great, black gloves cover his hands, his only garment. His eyes are different colors. In the mirror she sees the glint of something metallic. A few centimeters in front of his eyes, leaping sparkles of light as if from a Roman candle. But what she sees is a needle, threaded with thin red sewing thread. It protrudes from his eye. It was your brother, he says quietly. You were twelve. Is it still there.

He does not move, she does not reply.

The gloves are like an answer.

Can the past leave a person and come back for them again. The past, leaving you and coming back at inconvenient times.

His face is her face.

Their bodies have worked through the night, have lain in various positions, limbs draped like honey spun from the comb. Condensation trickles down the panes, both the windows are punctured. Through the glass one sees the sun upon the rooftops. Other planets are visible too, one is very near, dissected by the corner of the window frame. The planets drift as if suspended in water, close by and far away, sedately, prompting one to attribute their slowness to the distance at which they are seen, though in actual fact it is all about the eyes.

The eyes are planets too.

The slowness lies between the objects.

The individual body, the individual planet, possesses unimaginable speed and is proceeding insanely toward destruction. She reaches up and raises her eye to her lips. With two fingers she presses the orb between them. She stands for a moment, the eye in her mouth, the planet soon to block out the light from the window in front of them. One has the feeling of everything closing in, and yet one might easily claim the opposite. That would be true as well.

Translation from the Danish

By Martin Aitken