Translating Maulana Hasrat Mohani’s “Silently, silently . . .”

According to the translators of Maulana Hasrat Mohani’s ghazal “Silently, silently,” their translation “functions something like the supertitles to an opera. Unless you hear an opera sung in the original language, the text of the supertitles is only a faint shadow of the experience.” In the essay that follows, Zack Rogow describes their collaborative translation process.

Audio recording by Hamida Banu Chopra

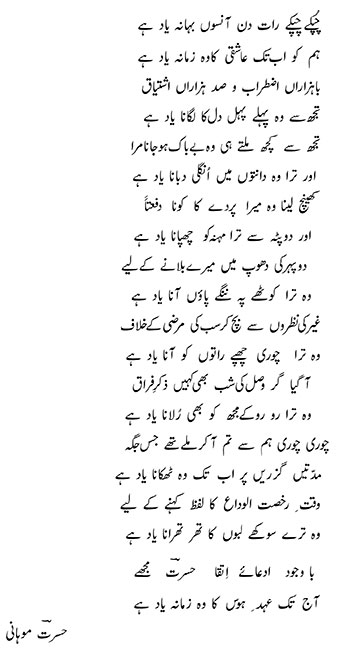

Ghazal

By Maulana Hasrat Mohani

Silently, silently, crying day and night – I still remember

All those days of our love – I still remember

With a thousand worries and even more fondness

I felt that first spark of love – I still remember

At our first meeting when I was instantly taken

By the shy way you bit your finger – I still remember

The time I yanked aside the curtain

And you hid behind your scarf – I still remember

In the heat of the afternoon you tiptoed barefoot

Across the terrace and called to me – I still remember

Dodging every stranger’s glance and everyone’s wishes

You stole away at night – I still remember

That evening when the mere thought of separating

Made the tears pass from your eyes to mine – I still remember

And the place where you came to meet me, secretly, so secretly

And so long ago – but I still remember

At the moment of our parting, you said goodbye

With your lips dry and trembling – I still remember

In spite of all your claims of piety, Hasrat,

That time of desire – I still remember

Translation from the Urdu

By Hamida Banu Chopra, Nasreen Chopra, and Zack Rogow

A three-person team translated Maulana Hasrat Mohani’s “Chupke, Chupke Raat Din,” each member bringing something very different to the mix. The lead was Hamida Banu Chopra, renowned in the San Francisco Bay area for her teaching of Urdu language and poetry and for the mushairas (recitals) she hosts at the India Community Center in Milpitas, California, often attended by more than two hundred fans of Indian and Pakistani poetry. Hamida is also celebrated worldwide among lovers of Urdu literature for her remarkable performances, where her command of the language in its most classic form combines with her ability to interpret the poems as she recites them, the way a jazz singer interprets a ballad. When I talk to Hamida about Urdu poetry, she rarely needs to refer to the texts—she has memorized all the important ones, and she knows the background material equally well.

The third member of our team is Nasreen Chopra, a nanotechnology physicist with a deep interest in Urdu poetry who is completely bilingual in English and Urdu. More on Nasreen’s role in a moment.

Our team had worked together before, translating the poem “There’s No Messiah for a Broken Mirror,” by Faiz Ahmed Faiz, and “Taj Mahal,” by Sahir Ludhyanvi. We had established something of a method. Hamida and Nasreen would do a rough draft into English of the poem. I would read that draft many times and also listen over and over to a recording of Hamida reciting the poem, trying to absorb as much as I could of the music and spirit. Then the three of us would meet and I would ask Hamida and Nasreen about the meaning of each word, trying to understand as well as I could—knowing only a few words of Urdu—the poem’s architecture, emotion, and web of references. My job has been to try and make the text as much of a poem in English as possible, creating fresh diction while trying to stay true to the meaning and sounds of the original.

As we made successive drafts of the poem, Nasreen would keep Hamida and me honest with her scientific method, testing the versions in both languages and weighing each word choice, as though tweaking the parameters of an experiment to ensure the most accurate results.

Ultimately, translating these poems from Urdu has involved many compromises. Urdu poetry is still as rhythmic and alliterative as Edgar Allan Poe’s English, while the thoughts are modern, so rendering the lines in speech that is fairly contemporary entails shifting some of the poetic energy into the imagery and into surprises in the diction.

One enormous challenge in translating “Silently, silently . . .” is that the poem is already incredibly famous in the Indian subcontinent. A YouTube video of the star singer Ghulam Ali performing this ghazal has hundreds of thousands of views.

There are three main reasons this poem has become so beloved. One is that it’s a deliciously romantic and nostalgic evocation of a youthful love affair. The second is that the poem was extremely well known decades before fame in India was all about Bollywood, and it became doubly renowned when Ghulam Ali’s version of the poem was actually featured in the soundtrack of the movie Nikaah, with the actors pantomiming the action of the poem. The third reason is that the author of this poem is a legend in India and Pakistan, one of the first outspoken critics of the British raj who braved harsh treatment in prison, which was meant to silence his uncompromising advocacy of independence. At one point Maulana Hasrat Mohani’s prison guards harnessed him to a gristmill, usually pulled by two oxen, and forced him to turn the millstone with an ox in the other yoke. He was kept in cells with common criminals as a way of breaking his spirit, to no avail.

The good news about the fame of the poet and this poem is that “Silently, silently . . .” already has a ready-made audience. The bad news from this translator’s standpoint is that such widespread recognition left us with fewer options. Playing with the meaning of the couplets in order to create a translation closer to the poem’s form did not seem possible. It would be like taking the summer’s day out of Shakespeare’s “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” in order to find a rhyme when translating this poem into another language.

This poem is a ghazal, a lyric form created in Arabic around 600 c.e. and refined in Farsi during the golden age of Persian poetry in twelfth-century Iran. The form is enormously popular in Urdu, and there is even an American Idol–style TV show in India featuring contestants singing ghazals.

Each couplet in a ghazal concludes with what is called in Arabic a qafiyah and a radif. The qafiyah is a rhyme that occurs in each stanza of the poem, twice in the initial couplet. The radif, a repeated phrase that ends each couplet, follows immediately after the rhyme. We were able to find a radif for “Silently, silently . . .” that worked for us in English as a close equivalent in meaning and feeling to the corresponding Urdu. But finding a rhyme that could occur immediately before this repeated word group in every stanza would have twisted many of the meanings of the poem too far from the well-known original.

The precise meanings of the lines felt particularly important here because the poem is perhaps the most famous example of a musalsal or continuous ghazal, where the couplets link to form a story. Normally, each couplet in a ghazal is a separate entity, united only by meter, rhyme scheme, and mood. Agha Shahid Ali has compared the couplets of a ghazal to two-line haikus. But “Silently, silently . . .” requires the story to river through the couplets.

The best modern Urdu poetry still retains the kind of musicality that you find in English only in “The Seafarer” in Anglo-Saxon or the best sonnets of Gerard Manley Hopkins, to cite two examples. For this reason, our translation of “Silently, silently . . .” functions something like the supertitles to an opera. Unless you hear an opera sung in the original language, the text of the supertitles is only a faint shadow of the experience. You have to hear the original of “Silently, silently . . .” in Urdu to appreciate the poem fully, and that’s why we have included a recording of Hamida reciting the verses.

Hamida uses a technique that has been passed down from generation to generation in Urdu called tehtul lafz, or recital style, as opposed to the singing style of performing ghazals. Her personal method is often to repeat the last line from the previous stanza when beginning the next stanza. This enhances and emphasizes the musicality, and contributes to the flow and intensity of the emotion in this ghazal’s narrative of youthful love.

Maulana Hasrat Mohani (1875–1951) was the pen name of an important Urdu poet and an outspoken and early advocate of complete independence for the Indian subcontinent. His real name was Syed Fazl-ul-Hasan. “Maulana” is a title of respect for an Islamic religious scholar. The name “Mohani” refers to his birthplace, Mohan. This poem is perhaps the most famous example of a musalsal (continuous) ghazal, where the couplets tell a linked story. The poem gained popularity when it was featured in the 1982 movie Nikaah, sung by the popular vocalist Ghulam Ali. The British government put Mohani in prison for his political advocacy, where he was made to experience harsh conditions. Following independence and the partition of India and Pakistan, he chose to remain in India, and he became a spokesperson for Muslims in that country.

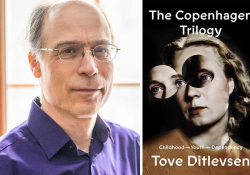

Hamida Banu Chopra teaches Urdu language and literature as a visiting scholar at the Indian Institute of Technology. She has also taught at the University of California, Berkeley, and is an internationally renowned reciter of Urdu poetry. She received her MA in philosophy from Rajasthan University and an advanced degree in Urdu from Aligarh University. Her co-translations of Urdu poetry have appeared in TWO LINES: World Writing in Translation, Circumference, and Born Magazine.

Nasreen Chopra is a physicist who has studied Urdu poetry. She is bilingual in English and Urdu.

Zack Rogow received the PEN/Book-of-the-Month Club Translation Award for his co-translation of Earthlight, by André Breton, and a Bay Area Book Reviewers Award (babra) for his translation of George Sand’s novel Horace. His English version of Colette’s novel Green Wheat was nominated for the PEN/Book-of-the-Month Club Translation Award and for the Northern California Book Award in translation. His co-translation of two Urdu ghazals appeared in the July 2013 issue of WLT; click here to listen to Shakeel Badayuni’s ghazal, recorded by Anshuman Chandra. Rogow teaches in the low-residency MFA in writing program at University of Alaska Anchorage.