Translating Robert Creeley into Russian

In April, following the death of Yevgeny Yevtushenko, I was digging through a wicker chest with old papers, looking at a colleague’s request for a few letters the poet had written to me. Suddenly I noticed two worksheets with algebraic problems, on the back side of which there was a lightly printed out old email in that very small font so typical for the turn of the century’s Internet correspondence. It was an email from Robert Creeley, sent to a long nonexistent address, in which he patiently answered my questions about two poems of his, “The Language” and “I Know a Man.” This accidental finding struck me: I had completely forgotten about the very existence of my translation—and, it turned out, about the poet’s generous response. Now it all came back to me, albeit not without gaps.

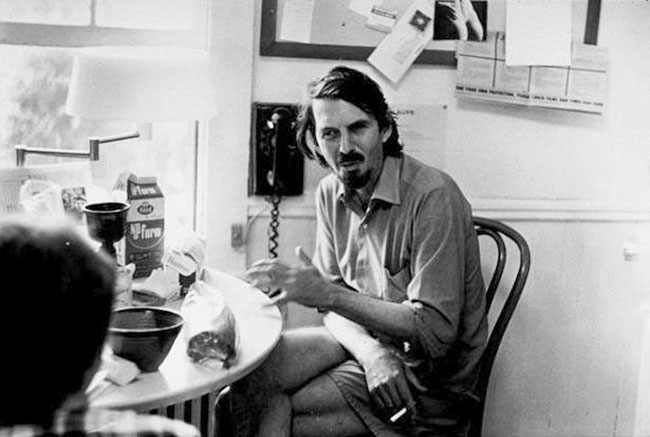

In the spring of 2000, I became interested in Creeley’s work. His abrupt style, his experience, his recognizable diction and mentality were very distant from mine, and maybe precisely for that reason I became so drawn to them. In such instances, I feel an urge to translate a few poems into Russian—something I normally do very rarely. I chose two very enigmatic and concise early poems, not yet knowing that they were two of his best known. It so happened that a friend, Russian poet Alexander Stessin, was at the time Creeley’s student at Buffalo; the two had developed a warm professor-student friendship. Alexander told Creeley about my work, and the poet suggested that I write to him with any questions.

He responded interlineally (the bits of my letter, which is lost, are in italics), generously clarifying the enigmatic places as much as they could be clarified in a medium other than the poem itself. In some cases, his clarifications confirmed my understanding; in some (e.g., the title of the second poem), they completely turned it in a new direction. Most importantly, his answers confirmed the intuitively found tone, the vernacular, the slang, the sounds, and the chimes of the Russian. As it often happens, Russian offered some wonderful phonetic and linguistic possibilities that underscored the tone and the meaning of the English poems.

Creeley’s answers confirmed the intuitively found tone, the vernacular, the slang, the sounds, and the chimes of the Russian.

I am writing these words on the 24th of May 2017 (on the day the Cyrillic alphabet is celebrated) and am suddenly noticing that this is precisely the date of Creeley’s letter: 24 May 2000. Yet this world is not coincidental at all! I hope that my rendering of the two poems is just like that: as noncoincidental and true to the thought and the tone of his confident lines as words uttered in another language can be.

P.S. Oh, and why algebra? At the time, I was a high school mathematics teacher.

* * *

“Words Ache . . .”: An Email from Robert Creeley

From: Robert Creeley

To: Irina Mashinski

Date: Wed, 24 May 2000

Subject: Re: 2 poems

Dear Irina Mashinski,

Let me help as I can. These poems were written years and years ago! In any case, here goes.

> 1. The Language

> 5th stanza – can you comment on “again” and the transition to the 6th stanza?

You’ll note that the phrase “I / love you” is in italics, whereas “again” is not. It’s an instance of the previous assertion: “Words / say everything” – that is, “I love you” is [a] fact “again” of [the] statement, “Words say everything.” So (the transition) the question then is, why then “emptiness,” what’s it “for,” given that “Words say everything.” How is it that so much remains empty despite “Words say(ing) everything” – as instance, “I love you.” Certainly a young man’s question!

> Also: “word full of holes aching” – does “aching” correspond with holes or with words – or both?

Words ache, holes cause aching – it all is [a] fact of the same circumstance, emptiness. (Note “word” here is “words” plural!)

> 2. I Know a Man

> (1) Does the first line continue the title?

No. In American idiom, “I know a man” is a familiar phrase used to imply that one has the right connections, can get what’s needed.

> (2) “which was not his name” (John? – or that man?)

“His” is the friend, whose “name” is not “John,” etc. Don’t ask me why! It’s a curious insistence on being circumspect, like they say.

> (3) Can you comment on the entire 3rd stanza?

“what can we do against it . . .” What can we put against or use to deal with “the darkness” surrounding, etc. etc. What have we got as defense against it – is the point here.

“or else, shall we & / why not . . .” Or should we just make a run for it, get out fast? “buy a goddamn big car, / drive” – all the same speaker, the first person of the poem

> (4) Who says this: Drive, . . .

See last comment – the end of the initial person’s speaking is the word “drive.” It’s the last word the initial speaker says.

> (5) HOW does he say “for Christ’s sake”?

Then “he sd,” the friend says, replies, “for / christ’s sake, look / out where yr going.”

> (6) the last line

Again as the comment for 5 makes clear, it’s the friend in those last lines (following “he sd,” saying, hey man, take it easy, “watch out where you’re going,” where this blasting off to the greater unknown may well take you. Just cool it!

So there you go. Good luck!

Best as ever,

Robert Creeley

Buffalo, New York

* * *

Роберт Крили

Перевод с англ. Ирины Машинской

Язык

Разыщи я

люблю тебя там

где зубы

глаза

прикуси,

осторож-

но не больно,

ты ведь

хочешь так

сильно так

мало. Слова

скажут всё.

Опять

я

люблю тебя,

отчего ж

пустота.

А затем

– заполнять.

Слышал слов

и слов предовольно,

полых,

полных боли. Речь

есть рот.

Кое-кого знаю

Это я другу –

я все время треплюсь,

– Джон,

грю – его не так, правда,

звали,–

тьма, грю, вокруг,

что нам делать,

хоть покупай, хрен его знает,

колеса побольше,

да несись-ка отсюда – а он грит,

Христа ради смотри

куда едешь.

Translations from the English

By Irina Mashinski

Editorial note: “The Language” appears in The Collected Poems of Robert Creeley, 1945–1975 (University of California Press, 2006), and “I Know a Man” appears in Selected Poems of Robert Creeley (University of California Press, 1991).