Home in the Face of Grief

A writer considers home as she remembers her partner of fifty-one years.

A writer considers home as she remembers her partner of fifty-one years.

I was born in Vienna and grew up in Australia. We didn’t speak German at home. My parents were “new” Australians for whom migration meant one country, one nationality. Australia.

My generation was a lucky one, with perhaps a short memory. Uni was free with a Commonwealth scholarship as the last year of the five-year high school system. I left Sydney straight after finishing my exams in French, German, and psychology. Not for a gap year. I wanted to see where I was born. Vienna. And after that, no plans.

Professor Hesse, my German professor at University of New South Wales, also a “new” Australian who had transited via a university career in then-apartheid South Africa, taught me that education wasn’t about marks and degrees.

He encouraged me to go to literary events, and at one, I met the Austrian poet Rudi Krausmann (1933–2019), who gave me a story by Heinrich Böll, “Die ungezählte Geliebte.” In English, it’s called “At the Bridge.”

It’s about a war veteran whose job is to count how many people cross a bridge. He secretly falls in love with a girl and does not include her in his statistics. When he gazes after her, others also slip through. I kept the photocopy of the story in my papers for years. Forgotten.

But I recently found it again, and I think the not-being-counted represents how I found my voice and perhaps my identity.

I’ve been going through all the bits of paper and knickknacks collected over the space of a life. Not just mine.

I’ve been going through all the bits of paper and knickknacks collected over the space of a life. Not just mine.

Günter, my husband and partner of fifty-one years, passed away last May, attacked by necrotizing pancreatitis and left to waste in the ICU for four months. It was nobody’s fault. Just one of those things. May he rest in peace. Peace was what he wanted.

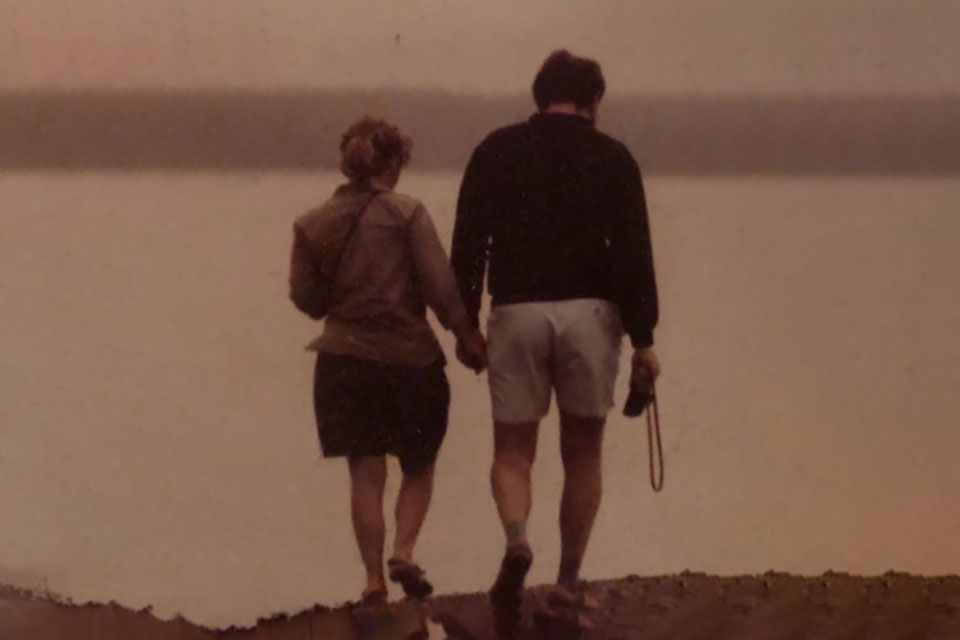

We met in Vienna, his hometown, in the 1970s. I’d just arrived from Australia to see the city where I’d been born. I’d grown up in Sydney and wanted to study translation at the University of Vienna. He said he was an installateur (plumber). I, declining a verb as a way out of my incomprehension, asked, “Was installen Sie?” (What do you install?). We both had to laugh, sealing our fate.

It was autumn, and our first date was a stroll in the central cemetery to watch the squirrels look for food to hoard against winter.

It was autumn, and our first date was a stroll in the central cemetery to watch the squirrels look for food to hoard against winter.

Where do people who don’t belong go to die?

I had begun to have flashes about belonging. Some came from the past, some from the present.

At school they said: “You look like us, but you don’t sound like us. Why don’t you go home? You don’t belong.”

But I want to be-long.

At the end of uni in Sydney, I returned to the land of my birth.

At uni in Vienna, where I was studying translation, they said: “You look like us, but you don’t sound like us. Why don’t you go home?”

You don’t belong.

Not yet, I said. I want to be-long.

Write It Down. Write It Down

It’s all grist for the mill, voices said, albeit small ones in my head.

“You don’t write like us,” their rejections sang.

“Why don’t you go home? You don’t belong.”

So I went home to a place that was burning. People locked their doors. Through the stench of burnt koala hide, I could smell something was very wrong in the Land of Oz.

“How dare you criticize the best country in the world?” a recently returned friend from a lifetime abroad said. My friend belonged. Both here and there.

But I did not and so we fell out.

What is home? Where is home?

Where your heart is?

Where your art is?

Where your arse is?

So many questions that leave you stuck with the only one left.

Where do people who don’t belong go to die?

A Flushed Flash

An Egyptian friend sent as a condolence: “We live and remember.”

Our daughter went alone to collect the ashes.

We had to have a paper from the embassy saying it was okay to take them to Australia. The paper came by email.

The Austrians didn’t like the idea of scatterable ashes being handed over just like that. Here they were placed in urns and buried in family graves so that family members could continue arguing for all eternity.

He wouldn’t have wanted that. We would scatter his ashes on his favorite golf course—Turramurra—a chopper course, he called it. It surely wouldn’t mind his ashes.

But we weren’t going till next year. Going forever.

“Put them under the stairs,” I said. They were in a shiny round tin in a plain brown cardboard box. It just fit.

On the wall above the stairs, there are photos of times of our lives, fifty-one years of fun and love. I see them from my bed next to the one missing his body.

“We mustn’t forget them,” I said.

“We won’t,” said my daughter. “The jewelry’s there.”

We laughed. He would have, too. Then we cried.

I waited for grief, but it didn’t come. So, I wrote flashes. I couldn’t bear more.

Two got published in Australia’s Pure Slush’s Lifespan Series entitled Achievement and Loss. Pure Slush had already brought my flashes on work (Volume 5), marriage (Volume 6), and home (Volume 7). It was a little like coming home to have my flashes accepted there.

Achievement (volume 8) and Loss (volume 9) were closer to the bone as I tried to come to terms with my grief but did not want to wallow.

I was going to post those two flashes here, but they left in boxes to be sea-freighted to Australia when possible, and are now in the eighty-five-box cargo sitting in Brno awaiting delivery to a Dutch port from whence they will sail to the Land of Oz. Am I going home? To where I be-long? I found the flash I had written and submitted to Achievement on my hard drive.

Tongue Poking (from Achievement)

“That’s quite an achievement,” I say as my husband pokes out his tongue. I poke out mine and hope he will do likewise. Tongue poking is one of the logopedic exercises he should do ten times a day to be able to speak again. 120 days in ICU have caused his muscles to atrophy, but he can still blow kisses of sorts as an “I love you.”

The doctor told him what would happen. No more assisted breathing. He will feel no pain. I hold his hand as the morphine kicks in. He looks straight through me.

“He can’t see you, but he can hear, smell, and feel you,” the palliative nurse says in answer to my unspoken question. I squeeze his hand as his breathing slows. I watch the numbers on the screen above his head. Then, in that last final flurry, he blows a kiss and pokes out his tongue.”

I can’t seem to find the flash entitled Loss. Maybe it’s too early.

Beginnings

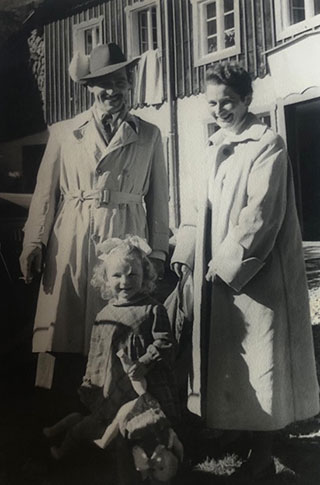

My parents immigrated to Australia with me when I was about three.

My parents immigrated to Australia with me when I was about three.

I left for Vienna when I was twenty to see my birthplace, find my roots. There I found my rock, the man I’ve been with for fifty-one years. The man who was also going to come to Australia. It was not to be.

My jobs took us to Helsinki, Brussels, Geneva, and then through conferences to Brazil, Argentina, Istanbul, and more. We married in Las Vegas for twenty-five dollars, honeymooned on a yacht in the Virgin Islands. Our daughter was born in Geneva and took off for Sydney to study.

Now she is with me in Vienna, sharing my grief, packing boxes for the move back to Sydney. Only the minimum. Just things that matter and are close to our hearts like papers and photos and paintings, and books.

Now she is with me in Vienna, sharing my grief, packing boxes for the move back to Sydney. Only the minimum. Just things that matter and are close to our hearts like papers and photos and paintings, and books.

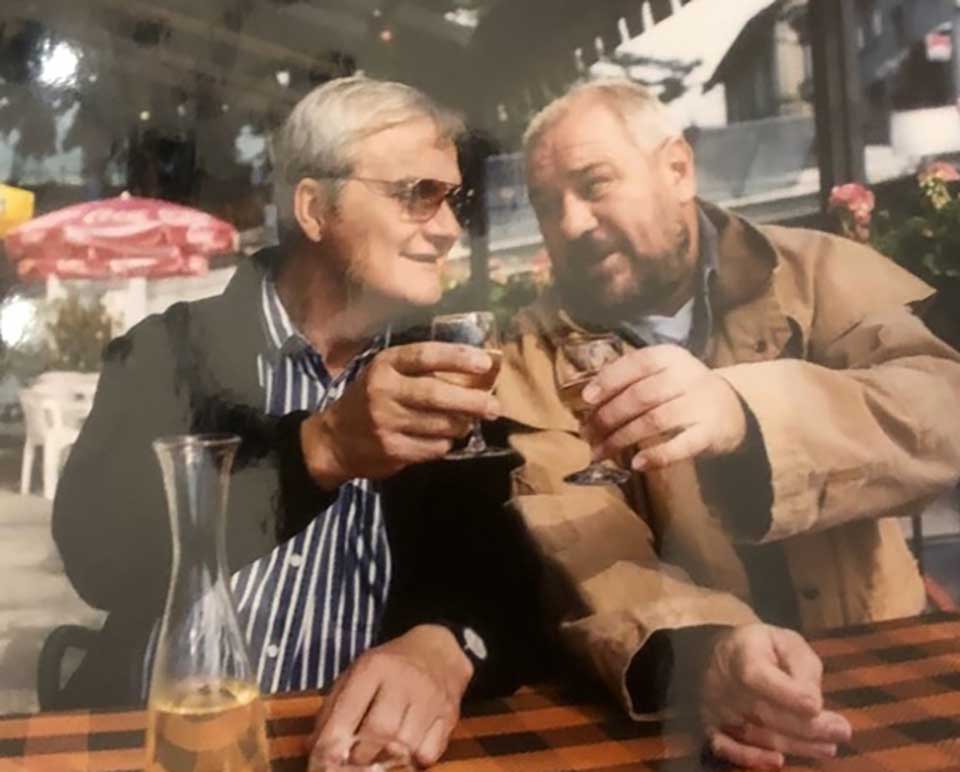

My husband had a Driza-Bone, which I gave to a young Australian friend in Vienna.

Here is Günter, in his Driza-Bone, enjoying a glass with Karli, an Austrian friend, married to a French woman and based in Switzerland where we also lived.

I could break it all down into slices of twenty, twenty years per slice: Sydney—Vienna—Geneva—Vienna—Sydney. Four were homes; he was with me for three.

So, going back to the question, Where is home?

I guess it must be where your heart is/was, would have been. Günter and I were going to get so old together; we both even quit smoking a good while ago.

Home will soon be Sydney again. I will nurse my grief, look at old photos, talk to my husband and thank him for the half-century we explored life and the world together. He was loved by young and old. He even danced rock ‘n’ roll in an Austrian kilt at our daughter Sydney’s wedding.

Home will soon be Sydney again. I will nurse my grief, look at old photos, talk to my husband and thank him for the half-century we explored life and the world together. He was loved by young and old. He even danced rock ‘n’ roll in an Austrian kilt at our daughter Sydney’s wedding.

It’s good that I’m going back to Sydney. I would be too lonely in Vienna. My daughter and her husband can put me up in the spare room of their flat until we find a house with a yard where I can have a granny flat built—a two-bedder so as to have a room for visitors.

I will have pots and plants and bookshelves. I will join the local library to keep costs down. I will become a minimalist, an independent one, not falling on anyone’s turf. My own woman, quoi! Maybe then, words will pour out of me, helping me to overcome my grief.

The stories will decide what they are to be about. I shall experiment, venture into the realm of crime—romance I need to leave aside for a while.

As the pendulum swings to the right in Europe, I’m a bit worried about what awaits me in the Land of Oz.

As the pendulum swings to the right in Europe, I’m a bit worried about what awaits me in the Land of Oz.

A new chapter—that’s the only way I can move on. I can start a new and exciting chapter and still go back and read what came before. I can also look ahead and see where life takes me in this last segment of my life. I can tell him all about it, spin tales to keep him close. I’ll put on some music. He liked Rod Stewart—maybe there’s a kilt-link there.

He didn’t have a funeral. We invited friends to come by in July and bid him farewell, the way he would have liked. They came from far and wide—Helsinki, Geneva, Vienna. His birthday was at the close of November, so our daughter cooked his favorite meal—meatloaf and mashed potatoes with a colonel for dessert (lemon sorbet with a shot of vodka). We were three at table—our daughter, Maarit; our lodger, Günther; and me. My Günter would have enjoyed it.

This will be the first Christmas without him. We have lots to do as we empty the house pending a sale. Yesterday, men came to pick up eighty-five boxes.

Things here are coming to an end. It may be a sign. Like my dry skin flaking off, making space for a renewal that will always hold him dear. I can hear him nodding.

Things here are coming to an end. It may be a sign.

It’s been a great ride all around the world and more. Those eighty-five boxes contain treasures that will come alive when we meet up with them in Sydney. Their contents will link to memories that will sustain me in the new chapter of my life.

Vale Günter Linsbauer: lover, husband, father of our wonderful Maarit, and as a friend said, gentle giant with a big heart. It’s been a pleasure and an honor to have shared the ride with you.

“What do you install?” I asked many years ago. A life well lived, a love well loved, are the answers that now come forth despite having been too short. I recall the Egyptian condolence I received, now so apt: “We live and remember.”

I hope I can do all the memories justice when I go “home,” where “home” is no longer a place, but a state of mind that will have to sustain me for at least twenty more years, for I have stories to write.

Vienna / Sydney