Claiming My Egypt

What of Egypt is left in the children of Egypt’s Jewish diaspora? The daughter of an immigrant reflects on what it means to be “truly Egyptian” in the context of her family’s transnational identity.

When my mother is on the Mediterranean shore—usually, these days, in the comfort of a modest Tel Aviv café—there is always a moment when she turns to the water, closes her eyes, and deeply breathes in the salty air. Then, her face still turned to the sea, she says, “I was born on this water.”

When she is in a playful mood, my mother will explain that what must have happened is that when she was born in 1946, in the Jewish hospital in Alexandria, Egypt, my grandmother cradled her in her arms and took her to the window. Facing the endless blue waves, Allegra, my grandmother, held her daughter’s tiny face in the direction of the glorious sea and whispered in French, “Regarde. Look.” And in that moment an impenetrable bond was sealed.

I love the beauty of the Mediterranean Sea, but I don’t have that same bond. I was born three decades later, thousands of miles away, across a sea, an ocean, continents, cultures, and languages. I was born to a mother formed and wounded by expulsion. A woman who was forced from her home, displaced from her family, removed from her sea.

The history of the erasure of the Jewish community in Egypt, as well as the stories of Egypt’s exiled Jews, have been solidly documented over the past thirty years. These works powerfully evoke the lives, communities, and cultures of the Jews while they were living in Egypt, the conditions that led to their dispersal, the difficult rupture that came with their forced migrations, and their assimilation in new homelands.[i]

But what of the children of Egypt’s Jewish diaspora? What of Egypt is left in us? What claim, if any, do we have to this country that has shaped who we are? Are we at all Egyptian?

What of Egypt is left in the children of Egypt’s Jewish diaspora?

To help answer these questions, I have turned to the autobiographical essays of women intellectuals of Middle Eastern descent: Henriette Dahan-Kalev, Ella Shohat, and Ghada Karmi.[ii] These scholars have each used their own historically contextualized, personal, and family histories of migration to give meaning to complicated layers of identity. And so I echo Shohat’s declaration: “It is crucial to say we exist.” The history and wounds of Egypt did not stop with our parents; they continued on to the next generation, contributing layers of identity that are at once rich, transnational, and displaced.

In Egypt

The Jewish community of Egypt numbered approximately 80,000–100,000 people at its peak in 1948.[iii] Although a minority group, Jews played a leading role in Egypt’s cultural and economic life, particularly in the urban centers of Cairo and Alexandria.[iv] But with the July Revolution of 1952, and especially with the rise of Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1954, life in Egypt became increasingly perilous for the Jewish community. The rise of Egyptian nationalism at this time was renegotiating identity in a way that actively framed them as “non-Egyptians.” Moreover, the violent wars that Egypt fought with Israel—which was established as the Jewish state in 1948—put all of the country’s Jews in a precarious position, whereby they were viewed with antagonism and suspicion as hostile aliens, even in cases where they were not Zionists and vocally asserted their loyalty to Egypt.[v] Gradually, Jews were forced out of the country that they had lived in for generations, with targeted expulsions in 1956, 1957, and 1967.[vi] These acts, combined with a general climate that made Jews socially and economically vulnerable, meant that within twenty years, this once-flourishing community was almost completely erased. By 1968 there were only 1,000 Jews in Egypt, by 1991 there were fewer than 200, and by 2020 only around 16 remained.[vii]

My mother comes from a typical Egyptian Jewish family, one that could have come out of the pages of Lucette Lagnado’s or André Aciman’s memoirs. They were deeply connected to, and lived as part of, the Egyptian Jewish communities in Cairo and Alexandria. Their lives were firmly intertwined with a large, extended family—the dynamics of which were at once mundane, fraught, and loving.

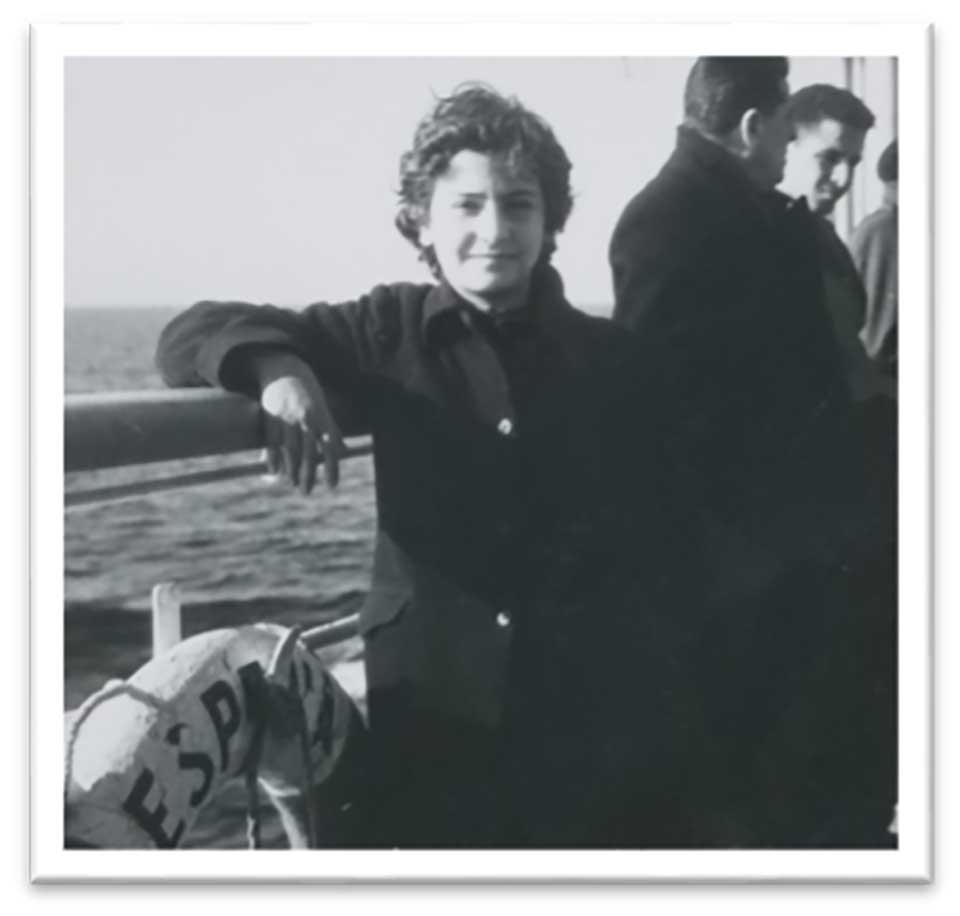

My mother left Egypt in 1955. Her parents no longer felt economically or personally safe as Jews there. And so—a few years after some relatives had gone and a few years before all the others—my grandfather decided that they, too, needed to leave. After a few years in Paris, they eventually moved to Vancouver, British Columbia, which is where I was born. But my mother has never told stories of holding me up to look at the Pacific Ocean, like her mother was said to have done for her and the Mediterranean. Through my Canadian-born, Ashkenazi father, I inherited the very defined, unbroken experience of belonging to a place that comes with the facets of a clear, undisturbed, modern national identity: citizenship, language, a local accent, physical community, familiar culture. And through my mother I inherited something very different.

Chou-Chou, Ya Rohi

During my time teaching at American universities, I met a senior Egyptian American professor who, when I told him about my mother, asked if I speak Arabic. I happily responded with the few words that I know, in a not-terrible accent. In return, he smiled politely and said nothing more. After our exchange, his disapproval registered and I felt silly, wondering why I had not simply answered “no.” I do not speak Arabic as a living, full language. Still, it had never occurred to me to say “no,” because the few Arabic words that I do know are not a shtick or an intellectual exercise—they are a vital part of me.

To the extent that my mother has one mother tongue, it is French. Like most Egyptian Jews, her family lived in many languages, and the way they communicated in their household was far from straightforward. My grandmother was fluent in French and Arabic, and comfortable in Greek and Italian.[viii] She spoke with her children in French but with her husband, my grandfather Abdu, in Arabic.[ix] For his part, my grandfather’s French was not strong. Arabic was his mother tongue, and his English was flawless. So, he spoke with his children in Arabic, but they responded in French.[x] This was a situation that my grandfather encouraged. As was common among upper-middle-class, urban Egyptians of his time, he insisted that his children receive a French education.[xi]

But historians of modern Egypt clarify that this would not have marked my family as outsiders at that time. For my grandfather, who was a banker, French was a language of necessity in the business world, and it would have offered his children the promise of eventual economic opportunities or business connections. But it was also a language of prestige and modernity, for Muslims and Christians as much as for Jews.[xii] And so these European languages were my family’s priority, and my mother and her siblings never learned how to read or write in Arabic. But Arabic was inherent to their life in Egypt, and the language was loved and respected by my grandparents. In addition to what she learned by hearing her parents speak, my mother picked up Arabic in day-to-day interactions, from movies, and from her family’s domestic workers.

When my sisters and I were young, my mother spoke to us in French, but in Hamilton, Ontario—where I grew up—English was the language of our home. My sisters and I retained some proficiency in the French language, and it took on a special, intimate role in our relationship with my mother. Our lullabies were the songs of French singers: Charles Aznavour, Yves Montand, and Edith Piaf. Our mother endearingly refers to us as chou-chou. And when we were children and she needed to give us motherly admonitions, especially in front of others, they were always in French: Ça suffit. Assieds-toi. Qu’est-ce qu’on dit? (Enough. Sit down. What do you say?). Today when she wants to say something that is not suitable for my children and my sisters’ children to hear, my mother will conspiratorially switch into French before smoothly moving back into English.

If French is the language through which my mother conveys to me maternal love and intimacy, my grandmother’s was Arabic. My Arabic words—the ones I shared with the Egyptian American professor—are almost entirely her terms of endearment. For my mother I am chou-chou, for my grandmother I was ya rohi or ya binti—my soul, my daughter. As an adult, after I learned a new Arabic phrase from my mother, I called my grandmother to try it out. This was a version of shavua tov, the traditional Jewish greeting used to wish someone “a good week” at the end of the Sabbath. “Gumaytek hadra, Nona,” I said over the phone. “May you have a green week.”[xiii] My grandmother was overjoyed: Ah ya binti! Gumaytek hadra, ya rohi.

If French is the language through which my mother conveys to me maternal love and intimacy, my grandmother’s was Arabic.

My other Arabic word is one that my grandmother gave to my mother and that she, in turn, passed on to me directly: akruta. In English it would be translated into something like “rascal,” but with love and bite to it. For my grandmother, my mother’s aunts, and my mother’s sisters, my mother was always an akruta. Very early on, my mother made it clear to me that I was one too, and now there is no question that my daughter is also.

Language seems to distance me from claims to Egypt. When a Palestinian friend met my mother for the first time, he later teased me, saying that my mother’s fluent French showed him just how Egyptian she really was. The implication—as I understood it—was that she was a colonizer, not a true Egyptian. We never discussed whether he considered me at all Egyptian; I feel certain he would have laughed at the notion. Certainly, if I were to be conversant in Arabic, then it would all be so much simpler; like Ella Shohat, I could confidently claim my place as a Jew from an Arab land. But the legacy Egypt left its Jews is far from simple. In Egypt, my family’s languages were rich, complicated, and intricately multidirectional. My patchwork of Arabic and French is the Egypt that I inherited. It is fractured, displaced, incomplete. It is broken and uprooted. It is intimate, loving, and familial. And it is no less Egyptian than another person’s flawless Arabic.

Family

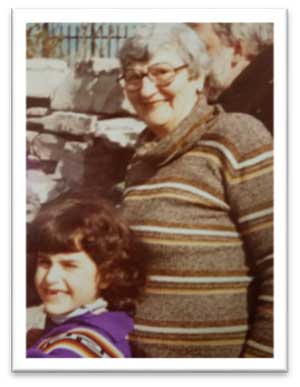

When I was a child, my parents, my two older sisters, and I left Canada in 1983 for a grand adventure across Europe. We were headed to Israel, where my father was taking a yearlong sabbatical at Ben Gurion University. Our time in Europe was long and memorable for me as a child, with exciting experiences in new countries and intensive fun with my sisters. In retrospect, though, it was much more than just a family excursion: it was a prolonged and disjointed reunion, as my sisters, my father, and I met my mother’s extended, dispersed Egyptian family for the first (and largely the last) time ever.

We went from London, to Paris, to Milan, to Geneva, and finally to Israel. And in each of these locations, there were meaningful reunions with aunts and uncles and cousins. On this cross-continental journey, my mother—now a thirty-eight-year-old woman—had the chance to spend time with the family members who had once anchored her day-to-day existence and whom she had last seen when she was a young girl. In every one of these new countries we found familiarity and family; we were met with a warm, complicated, and generous embrace. For the first time I had the opportunity to see my mother as a person who was not a transplanted exotic. Among her warm, enveloping, extended family, she fit. Among them she was not the Egyptian, French, Mediterranean, Sephardic-Jewish woman in WASPy, restrained, Ashkenazi-Jewish, Anglo-Canadian, snowy Ontario. She gained a new dimension with these people who looked like her, spoke a million languages like her, and who seemed to delight in the child she had been and in the woman she had become. For me, as a child, these encounters across the world were great fun. But now, as an adult, these encounters feel more complicated, as I wonder what we lost through this dispersal.

Growing up, the pastness of Egypt for me was something I never questioned. Egypt had once belonged to my family, or—at least—my family had once belonged there. But there was nothing for us there anymore, and we would certainly never return. For the vast majority of my life, the only other Egyptians I had ever met were a few other Jews or their children. The break from Egypt as a physical location, as a country of belonging, was just as stark for them as it was for my family. And so this pastness was reinforced. But when I moved to America when I was in my mid-thirties, for the first time I met Egyptians who are not Jewish. Like my family, they are living abroad, but unlike my family, they have Egypt to return to. They have a continuity that had never occurred to me. As they extend their horizons abroad, Egypt gives them an anchor of identity and family to which they can choose, or choose not, to return. The contrast between their continuity and my discontinuity from the same country, their identity being allowed and legitimate and ours cut off and denied, pushed me to see that what I had accepted as a mythic past is first and foremost a contingent history. And for the first time I began to imagine what a counterfactual history could have looked like, with visits to my grandparents in Cairo and summer trips to Alexandria. I could imagine an unbroken sense of belonging—of being Egyptians in Egypt—spending time in the home my mother grew up in, with the organic and strengthening presence of family all around, not scattered around the globe.

What I had accepted as a mythic past is first and foremost a contingent history.

Salman Rushdie has described the state of being a migrant as a “burdensome freedom.” To see things clearly, he suggests, you need to cross a border.[xiv] I grew up seeing my mother’s story in this way. My mother conveyed to me that leaving Egypt was burdensome: it was hard to become poor; it was hard for her parents to find a home they felt safe in and suited to outside of Egypt; it was hard, in the overwhelmingly Ashkenazi Jewish community in Vancouver, Canada, for her to fit in. But my mother also conveyed to me that her migration was a freedom: life is easier with less material objects to worry about; it’s fun to bring an interesting and different culture to share with new neighbors; it’s valuable to know different languages. The focus my mother was given and transmitted was how much we have, despite how much was taken away. But what fades into the background—and is the undercurrent that shapes this experience—is that something profound was indeed taken away from us. Historian Tara Zahra describes how, in contemporary Europe, the privilege of mobility is “associated with freedom.” But she also brings attention to the fact that, for many, the idea of “true freedom” is one that allows a person the choice to stay home.[xv]

In 1983, when we arrived at the home of my grandmother’s sister in Italy, I was the first up the stairs as Tante Flore eagerly opened her apartment door. When she saw me her face had a look of shock and temporary confusion as she called out my mother’s name, exclaiming, “It’s Racheline!” A moment later my mother followed and the two women laughed and embraced. In Egypt, my mother was the akruta who used to defy her aunt and pick rose petals from Flore’s garden to wear as flaming-red fingernails. In Egypt, Flore was certain that her niece brought her good luck, and she would insist that my mother stand next to her at the gambling table to ensure a generous win. It was in Tante Flore’s house in Alexandria that my mother would gather with her family for their indulgent summer beach holidays. And when the extended family was chipped apart, with each unit fleeing Egypt for whatever country would have them, it was my mother who held on to Flore’s correspondence, a pile of handwritten cards from across the world, effusive with love and longing: “Je pense souvent à vous tous”; “je t’embrasse tendrement”; “ta tante qui t’aime”; “ta soeur qui t’aime”; “tu me manques beaucoup” (I think of you often; I embrace you tenderly; your aunt who loves you; your sister who loves you; I miss you so much).[xvi] In 1983, when I bounded up the stairs in Milan and Tante Flore and my mother were reunited, the last time they had seen one another was nearly thirty years before, when my mother was a child who looked like me. Our time at Flore’s home in Milan was loving and crazy. The short visit was a comedy of errors that became a much-repeated story in my family lore. It was a reunion that, for a brief moment, brought together beloved members of a family that once had the freedom to stay together at home.

Karakib

My mother has almost no attachment to material things. She regularly goes through her closet, giving away books, clothes, makeup, and jewelry, keeping her own possessions to a minimum. Above all, she abhors knickknacks, which she always refers to, in Arabic, as karakib. Although it almost certainly has a fuller meaning, I grew up understanding that karakib is only negative. It is a word my mother almost always says with disdain and with a wave of her hand: “It’s karakib, Rhona. Eh, who needs it? Thrrrow it away.” If some object has the bad luck of being labeled by my mother as karakib, its fate is sealed; it has no chance of surviving long in her home. There is something about this quality of hers that I deeply admire. But I don’t fully share this trait. I yearn for heirlooms and objects that have longevity and stories. I am less eager than my mother to part with possessions.[xvii] As a result, and for as long as I can remember, this has been a combustible point between us. Even to this day—as a middle-aged woman and an elderly woman—my mother and I can get into thunderous arguments about things she thinks should be thrown away and things I want to keep.

Many years ago when I was in high school in Hamilton, a friend came for a visit and my mother served her tea in a delicate cup that had once belonged to a beloved neighbor. This neighbor had given it to my mother as a special gift, and my mother treasured it. When she learned how precious this fragile cup was, my friend was nervous and asked whether she could have a different one instead, so that she wouldn’t risk breaking an irreplaceable memento. My mother quickly set her at ease, saying something she truly believes: “If it breaks, it breaks. We should use and enjoy things, not leave them to collect dust and become karakib.” I remember this encounter with pride all these years later. To me it exemplified the welcoming nature of our home. Unlike some of the stately houses I saw around me in Ontario, my mother made it clear that our priority was on creating a home where people could be at ease. We would not be slaves to objects, as beautiful and as valuable as they may seem.

But there were similar interactions that were more irksome. When my close friend Ruthie was over, wearing a sweater that she had borrowed from me, my mother—with typical warmth and informality—suggested that since she liked it so much, Ruthie should just keep my sweater. In my mother’s view, my high school wardrobe was ridiculously overflowing. The more we get rid of, the better. This amused Ruthie and annoyed me. (I made it immediately clear that there was no way I was giving her my sweater.) But, bothersome as this was, my mother was just applying a philosophy that she fully adheres to herself: there is almost nothing she owns that she would not give away. If ever my sisters and I comment that we like something of hers—even if only to compliment her—invariably my mother’s response is, “You like it?!? Take it!”

This characteristic of my mother connects to the experiences she had and the ideas she internalized as a refugee. Of course, letting go of material possessions is a defining part of the immigrant, displaced-person, and refugee experience throughout history and across the globe; out of necessity, you need to shed objects that weigh you down and prohibit movement. There is an important story that’s part of my mother’s departure from Egypt. When they first arrived in Paris, her family had no money and was given food and modest housing through Jewish aid organizations. They ate their meals at a soup kitchen run by the Jewish community. One of the first times, standing in line with her father to receive these handouts, she asked him whether their new poverty made him sad. But he comforted her, saying, “The less possessions you own, the less worries you have.” When my mother relates her story of leaving Egypt, this exchange with my grandfather is at the heart of what she remembers. The formative lesson for her has been to hold on to what is essential and to be willing to let go of karakib.

The formative lesson for my mother has been to hold on to what is essential and to be willing to let go of karakib.

Full Circle

My copy of André Aciman’s memoir, Out of Egypt, was given to me as a present by my mother. When the book was published in 1994, I was living in Jerusalem, where I had just begun my undergraduate degree at the Hebrew University. Out of Egypt was the first book that brought the story of Egyptian Jews to a broad, English-speaking audience. An avid reader, my mother immediately adored it. She gave copies to whomever she could, eager to share what she saw as a representation of her own family’s experiences. Eventually I would find that I identify more with the writing of Jaqueline Shohet Kahanoff and Lucette Lagnado: their voices speak to my heart and to the almost-entirely female understanding of Egypt that I inherited.

Still, I loved and was grateful for Out of Egypt. This book showed me how the piecemeal stories that I received from my family over the years belong within a full, vibrant world. Most of all, I treasured the copy my mother gave me. In her attentive calligraphy she inscribed the front pages. She wrote in French of her own exodus “out of Egypt” and of my own life in Jerusalem. She ended by saying that, now, with me in Israel, we had come full circle. As complicated as this sentiment is, my mother touched on something true. Egypt, as a physical space, has been taken from Jews. But nearby, in Israel, I found my Egypt like nowhere else.

I found it in the plethora of Egyptian Jews and the children of Egyptian Jews, people whose lives are enmeshed in Israeli culture and society, people who often look like me and my sisters, people who share fragments of my background and many of my questions. Through this Egyptian Jewish community that I had never encountered before, I was able to see parts of myself, parts of my mother, and parts of our family in others and connected to a bigger experience.

My first friend of Egyptian heritage was Caroline, another student at the Hebrew University. Caroline was born in Antwerp, and her mother was born in Cairo. We had an immediate bond when we discovered our shared connection, and we spent years of friendship exploring this subject in conversation. Then there was my grandmother’s cousin Rachel and her husband, Lucien. When I was admitted to a PhD program in Beer Sheva, the city where they lived, Oncle Lucien phoned me to say how eager they were to help me settle in since, nearly forty years earlier, my own grandparents had helped them when they were forced out of Egypt. Rachel and Lucien had arrived in Paris in November 1956, after my mother and her family had been there for a year. At the time Lucien was thirty-one, Rachel was twenty-nine—in the early stages of a delicate pregnancy—and their son, Joseph, was three. Lucien had been a teacher at Victoria College in Alexandria where Hussein bin Talal, the future Hashemite king of Jordan, had been his most famous student.[xviii] While Lucien looked unsuccessfully for work in Paris, my grandmother Allegra took care of her cousin Rachel, and my ten-year-old mother doted on little Joe. In May 1957—when Rachel was seven months pregnant and they had exhausted all other options—they arrived in Israel, because there was nowhere else for them to go.

Tante Rachel and Oncle Lucien stayed true to their promise of welcoming. They always received me in their Beer Sheva home—whether for casual evening visits or for special Jewish holidays—with unreserved warmth.

I found in them a deeper understanding of who my grandparents had been: the particular lilt of their Egyptian accents, the earnestness of their Jewish faith, and the depth of connection they had as family members who had cared for one another through pregnancy, childbirth, and loss. And seeing Rachel and Lucien in the midst of their modest and beautiful life in the modest and dusty city of Beer Sheva, so far from the home and life that had been taken from them in Alexandria, I gained a deeper understanding of the extraordinary but heartbreaking work that our families had put into building new lives in foreign countries.

I gained a deeper understanding of the extraordinary but heartbreaking work that our families had put into building new lives in foreign countries.

In Israel I also found my Egypt in the food.[xix] I delight in discovering these vital parts of my family—which had been domestic and unusual in our Canadian setting—in the everyday sphere in Israel, where they are familiar, accessible, and public. I remember one of the first encounters like this in Jerusalem soon after I had moved there in 1994. I was in Meni Minimarket, a nondescript corner store on Bezalel street in Nachlaot, and the owner had put out large trays with rows of freshly baked, handmade ma’amoul. Never before had I seen ma’amoul outside our home, and certainly not as a part of everyday life. These cookies—round, stuffed with dates and walnuts, and sprinkled with icing sugar, each one carefully hand crimped with tongs that are specially made for this precise purpose—made an appearance in our family home for bat mitzvahs and other rare celebrations that would justify the intensive labor and love that they required. Seeing my grandmother’s ma’amoul so organically a part of the outside space—my public space—for the first time was thrilling. And it continues to delight me so many years later: the fresh molocheya leaves a local chef shares with my mother from his garden; my grandmother’s khak sold in supermarkets as a packaged, everyday food item; a dish made with d’oa in a local Beer Sheva restaurant; and my mother’s beloved mangoes, an unusual treat growing up in Hamilton, found in overflowing heaps in every market.[xx]

There are many ways that my family does not fit in Israel. And yet I have found here balms for my mother’s Egyptian wounds. It has given to her a restorative home and a new type of belonging: a Mediterranean society, situated on her sea. It is a place where my mother’s history and displacement are understood, where her Jewishness is at ease, and where her otherness is familiar. Yet, of course, at the heart of this country’s foundation is its own painful story of refugees, with the many Palestinians who were forced to leave their homes during the 1948 war that established the new state of Israel.[xxi] By choosing to make our home here, my family is seen angrily by some to be perpetuating colonial injustices against the Palestinians. But, of the choices we have, I cannot see that it is more just for us to live anywhere else. To the extent that Jews are allowed to have a home in the world, going from Egypt, to France, to Canada, to Israel is perhaps as full a circle as any.

Of Egypt

I have never heard my mother refer to herself unequivocally as Egyptian. Despite the fact that she was born there, to Egyptian-born parents, that her father worked in the National Bank of Egypt, that her large, extended family lived almost exclusively in Egypt, and that her family was fully immersed in the country’s life and culture, “Egyptian”—that explicit claim to belonging—was never a proper fit. She says of herself that she is “from Egypt” or “born in” Egypt.[xxii]

When I recently asked her if she is Egyptian, my mother returned to the way she was once introduced at a party in Canada: “Racheline is a citizen of the world!” This transnational identity, which she embraces, is beautiful and appropriate to who she is and where life has taken her. As a citizen of the world, she brings to life what Ella Shohat has described as the “syncretic identities” of Jews from Arab lands. My mother, like Shohat, is a woman who does not “dissolve so as to facilitate ‘neat’ national and ethnic divisions.”[xxiii]

For my part, if my mother does not consider herself Egyptian, then it seems silly for me to consider myself to be. But I have started to wonder if this is another way that our family has come to embrace a “burdensome freedom” that was not our choice. By refusing to insist that we are Egyptians—full stop—are we not simply accepting what Nasser decided for us? Is this not the outcome of the slow Egyptian erasure of their Jewish community that took place over decades? Someone has successfully convinced themselves, and the world, and us that we are not—and never were—truly Egyptian.

Someone has successfully convinced themselves, and the world, and us that we are not—and never were—truly Egyptian.

My family will never return to Egypt. Our physical break from the country is final, and the Levantine, “syncretic identity” that I inherited from my mother continues on with me and my sisters (much as I might like to fight it). For the children of this Jewish diaspora, Egypt is a country that destroyed our community, stole our property, tore apart our families, and scarred our parents. It nourishes our food, enlivens our tongues, imprints our faces, and gives life to our stories. In this way, we are Egyptian. And “it is crucial to say we exist.”[xxiv]

Norman, Oklahoma

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to the people who read and took time to offer their comments on earlier drafts of this essay, including Daniel Simon, Noam Stillman, Kathleen Brosnan, Shir Alon, and Yair Pincu, as well as my many wonderful colleagues in the University of Oklahoma History Department Workshop. This project was partially funded by a 2020 grant from the OU Arts and Humanities Forum as part of the theme “Rupture and Reconciliation.” Without the encouragement and financial support that their grant offered me, I am not sure I would have had it in me to continue with this work during the pandemic, so I am particularly grateful. Above all, I must thank my mother, Racheline Dayan Seidelman. I don’t think I could ever fully express my gratitude and love, but I hope that, in some ways, this essay is at least a start.

[1] Memoirs: André Aciman, Out of Egypt (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1994); Lucette Lagnado, The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit: A Jewish Family’s Exodus from Old Cairo to the New World (HarperCollins, 2007); Lucette Lagnado, The Arrogant Years (HarperCollins, 2012); Joyce Zonana, Dream Homes: From Cairo to Katrina, an Exile’s Journey (Feminist Press, 2008). Essays, short fiction, and novels: Mongrels or Marvels: The Levantine Writings of Jacqueline Shohet Kahanoff, ed. Deborah Starr and Sasson Somekh (Stanford University Press, 2011); Ronit Matalon, The One Facing Us: A Novel (Metropolitan Books, 2013); Orly Castel Bloom, The Egyptian Novel (Dalkey Archive Press, 2017); Yitzhak Gormezano Goren, Alexandrian Summer (New Vessel Press, 2015); Yitzhak Gormezano Goren, Blanche (Am Oved, 1986) [in Hebrew]; Yitzhak Gormezano Goren, Alexandrian Beaches (Ha Kibbutz Ha Meuhad, 2018) [in Hebrew]. Cultural studies: Deborah Starr, Remembering Cosmopolitan Egypt (Routledge, 2009); Aimée Israel-Pelletier, On the Mediterranean and the Nile: The Jews of Egypt (Indiana University Press, 2018). Film: Salata Baladi, dir. Nadia Kamel (2007). Historiography: Gudrun Kramer, The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 (University of Washington Press, 1989); Joel Beinin, The Dispersion of Egyptian Jewry (Stanford University Press, 1998); Liat Maggid Alon, “The Jewish Bourgeoisie of Egypt in the First Half of the Twentieth Century: Modernity, Socio-Cultural Practices and Oral Testimonials,” Jama‘a 24 (2019): 7–32; Alon Tam, Cairo’s Coffeehouses in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries: An Urban and Socio-Political History (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2018); Michael Laskier, The Jews of Egypt, 1920–1970: In the Midst of Zionism, Anti-Semitism and the Middle East Conflict (NYU Press, 1991).

[1] Henrietta Dahan-Kalev, “You’re So Pretty—You Don’t Look Moroccan,” Israel Studies 6, no. 1 (2001): 1–14; Ella Habiba Shohat, “Reflections of an Arab Jew,” Marxists Internet Archive; Ghada Karmi, “The 1948 Exodus: A Family Story,” Journal of Palestinian Studies 23, no. 2 (1994): 31–40.

[1] Aimée Israel-Pelletier, On the Mediterranean and the Nile: The Jews of Egypt (Indiana University Press, 2018), 21; Liat Maggid Alon, “The Jewish Bourgeoisie of Egypt in the First Half of the Twentieth Century: Modernity, Socio-Cultural Practices and Oral Testimonials,” Jama‘a 24 (2019): 13.

[1] Michael Laskier outlines Jewish contributions to Egyptian life in The Jews of Egypt, 2; Najat Abdulhaq’s study explores this situation in careful detail: Najat Abdulhaq, Jewish and Greek Communities in Egypt: Entrepreneurship and Business Before Nasser (I. B. Tauris, 2016).

[1] Noam Stillman, The Jews of Arab Lands in Modern Times (Jewish Publication Society, 1991); Elinoar Bareket and Racheline Barda, “Egypt,” in The Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, ed. Norman Stillman (Brill, 2010).

[1] Bareket and Barda, “Egypt.”

[1] Bareket and Barda, “Egypt”; Stillman The Jews of Arab Lands, 177; Declan Walsh and Ronen Bergman, “A Bittersweet Homecoming for Egypt’s Jews,” New York Times, Feb. 23, 2020 (accessed Feb. 9, 2023).

[1] Interview with Racheline Seidelman, July 2016.

[1] Interview with Claudette Dayan, Nov. 2019; interview with RDS, Nov. 2019.

[1] Eventually, when they moved to Vancouver and my mother learned English, she and her siblings would respond to my grandfather in English. He continued to speak with them in Arabic. Interview with RDS, Nov. 2019.

[1] Interview with Racheline Seidelman, July 2016.

[1] Liat Maggid Alon, “The Jewish Bourgeoisie of Egypt,” 16, 18; see Joel Beinin, The Dispersion of Egyptian Jewry: “French was the lingua Franca for the entire business community. Knowledge of a European language was virtually a requirement for a white-collar job in the modern private sector of the economy and constituted significant cultural capital” (50); “Decades after formal independence, Egypt’s upper classes continued to regard the European imperial powers as cultural models” (54). When describing the cosmopolitanism of the prominent Jewish Egyptian Qattawi family, Beinin writes of Yusuf “Aslan” Qattawi, who was a contemporary of my grandfather: “His French education was not a marker of otherness or a political liability. It was a prestigious symbol of modernity and progress common to the sons of the landed elite, the business community, and many leading intellectuals of the early twentieth century, Muslims and Christians as well as Jews” (46).

[1] This idea of the “green week” comes across beautifully in Lucette Lagnado’s book when she describes men returning home from synagogue at the end of the Sabbath holding green sprigs of myrtle. Lagnado, The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit, 29.

[1] Salman Rushdie, Imaginary Homelands (Penguin Books, 1992).

[1] Tara Zahra, The Great Departure: Mass Migration from Eastern Europe and the Making of the Free World (W.W. Norton, 2010), 290.

[1] Racheline Seidelman, personal archive; cards from Flore to Allegra and family, 1950s–1980s.

[1] In the moving memoir by the Jewish Egyptian American author Joyce Zonana, I found both my own feelings and my mother’s reflected in the author’s thoughts about heirlooms. “For most of my life,” she writes, “I have been baffled by the American passion for antiques, the delight taken in the heavy, cumbersome pieces that filled the farmhouses and prairie homes of my friends’ ancestors.” But then, encountering her partner Kay’s own family heirlooms, Zonana “began to understand.” She addresses Kay with wonder and envy: “What wealth you have, what a great inheritance. [. . .] You have your grandmother’s things.” Joyce Zonana, Dream Homes: From Cairo to Katrina, an Exile’s Journey (Feminist Press, 2008), 6.

[1] Victoria College in Joel Beinin, The Dispersion of Egyptian Jewry, 50.

[1] Of course, I am very cognizant of the nostalgic power of food. As Joel Beinin puts it so well, “The warm and positive associations of food are an ideal medium for nostalgia” (216). But historian of psychiatry Rakefet Zalashik also reminds us not to dismiss the positive and valuable power of nostalgia.

[1] In Dream Homes, Joyce Zonana’s mother talks about her love of mangoes from Egypt (114).

[1] As a result of the 1948 war, around 750,000 Palestinians became refugees, after either fleeing the dangerous conditions of war or being actively forced from their homes as part of Israel’s military policy. The 150,000 Palestinians that remained became Israeli citizens and developed into what is now the country’s large Arab Israeli minority.

[1] I understand that there is no simple explanation for why my mother doesn’t unequivocally identify in this way. The tricky question of whether Jews and other minorities considered themselves, or were considered, Egyptian permeates studies on modern Egypt. But mine is a contemporary question and a contemporary claim. In our current landscape of changing Middle Eastern identities, it is appropriate that the Jewish minority and their descendants be identified as fully Egyptian, should we so choose. One of the most useful articulations I have found for this issue comes from the public history website egyptmigrations.com, when explaining the name they chose for their project: “We settled on ‘Egypt Migrations’ for two important reasons. First, ‘Egypt’ does not ascribe a national affiliation for migrating actors, while still recognizing the power of the nation and its borders on people’s lives. In short, we may be from Egypt, but we may not all see ourselves as Egyptians” (accessed June 7, 2023).

[1] Shohat, “Reflections of an Arab Jew.”

[1] Here again I use the phrase from Shohat’s “Reflections of an Arab Jew.”