Culture to Free Our Children: Looking Back at My Work over Five Decades

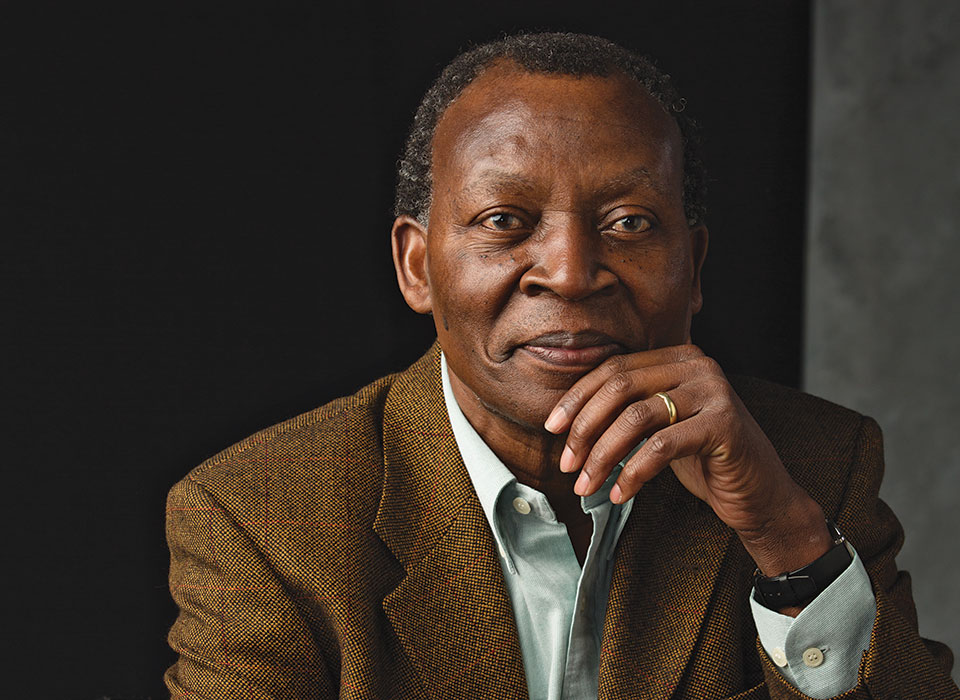

I feel greatly honored in that such a prestigious award, bestowed by a truly distinguished American institution, is an immense recognition of my role in Africa’s contribution to children’s literature.

Unlike most other children in the small town in Ghana where I grew up, I had a father who loved to read, so there were many books and magazines at home. Unfortunately, there were no “children’s books” besides school textbooks, and even those, too, were scarce. But I grew up during the years when well-educated and talented people were constructing the foundations of intellectual and cultural identity for our newly independent country, and again I was fortunate to be close to some of them. I simply took on the task of creating the kind of children’s books that I would have loved to have when I was a child. At that time, most books that we saw were written and published abroad and imported to Ghana. My goal then was to create books in which local children engaged in their usual activities and real-life experiences in environments and conditions that were familiar to them. So I observed fishermen and their activities at the local beach, produced a story, and illustrated it under the title Tawia Goes to Sea (1970), which received the unesco citation and went international.

However, over the following decade the country’s economy deteriorated to the extent that much printing and publishing activities ceased for lack of imported spare parts, supplies, and, particularly, paper. In 1981 when my second book, The Brassman’s Secret, was published, it was actually printed on pink poster board, thanks to an adventurous local businessman who brought it from Brazil. My next book, The Canoe’s Story (1982), was also published by another daring local businessman on bond paper meant for typewriting machines.

Following these experiences and difficulties I left to study in the UK and to pursue more writing from there. I wrote and illustrated Cat in Search of a Friend (1984) in the UK but did not find a publisher immediately, so I took it to the Frankfurt Book Fair, where I had been invited to speak. The first publisher I showed it to, Jungbrunnen, offered me a contract, and it won the Austrian National Prize and the BIB Golden Plaque (1985).

I have since written and illustrated a number of quite successful books of African background for children and young people. I had aimed to cover the rich regional diversities of Ghana initially, then the continent as a whole, but I have only managed three regions of Ghana and one each about Zimbabwe, Lesotho, Namibia, and South Africa. I have also tried to help in other ways to raise the quality of writing, illustrating, and publishing for children and young people in Africa, often as a trainer in workshops, by writing reviews, serving on juries for competitions, and presenting papers at institutions and conferences.

Influences

As a child, I enjoyed our folktales, which I often heard firsthand from my parents and grandparents—it was possible at that time. Unfortunately, by the time I had my own children, this privilege that I enjoyed had changed considerably, owing mainly to urbanization and the consequent disintegration of traditional family systems. Nowadays, many children in Ghana only know some folktales from textbooks and TV programs.

Much later, as I was growing up, I got to read stories from and about faraway places. Though these were always fascinating, the pleasure of reading them made me wish very much that there would have been similar books with local characters in familiar surroundings.

Much later, as I was growing up, I got to read stories from and about faraway places. Though these were always fascinating, the pleasure of reading them made me wish very much that there would have been similar books with local characters in familiar surroundings. Other books that were available and still rather few were in our local languages. These were usually published by missionaries who had previously translated the scriptures into those languages. This meant that books in our local languages were firstly extensions of that project. Other than that, they contained folktales that had been selected for their moral values. In that sense, those books only continued with the oral narratives, except that they could be read in collected form. I am of the opinion that the practice has strong influence on Africa’s literary outlook.

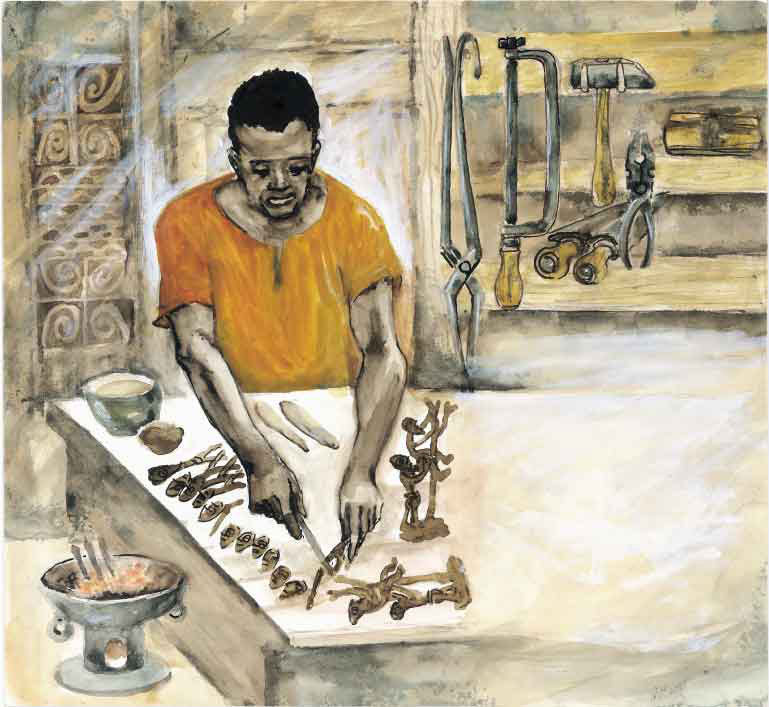

Another important influence on my work is my art education. For example, as an artist, I couldn’t help admiring the sculptural power of the “gold weights” and wondering at the mystique surrounding them. I watched craftsmen producing them when I visited my grandmother, though disappointingly, only for the tourist market. My inspiration came initially from owning a set that I could look closely at and touch as frequently as I wished and contemplating as I did so. They grew and grew until I really had to know more about them—then imagination did the rest. The outcome of this fascination is Kwajo and the Brassman’s Secret, cited above. The wise meanings of the various figures in the book are traditional, as is the historical context. Kwajo’s magical experience is, however, fiction.

My training in art taught me to observe the world around me with keen interest. And possibly, one of the most powerful spells of influence I came under as a child was a man that I had met at my grandfather’s house. He claimed to know the language of everything and often told us what he claimed to be conversations between dogs, cats, trees, fowl, pots and pans, etc., that he had overheard. I thought he must be an extremely clever man and would have liked to be a little bit like him. That was a while before I turned five. I was told years later by my mother that the man was in fact a patient at the local psychiatric hospital, but it still did not bother me. It gave me a fairly multiple and composite perspective on knowledge and tolerance, essentially “multi-literacy.”

Since all those years back when I started, I have had the opportunity to learn more and gained more insights and experience. I have come to believe seriously that culture is, actually, essential knowledge which gives us freedom to live and act and behave and express ourselves in ways that are recognized and accepted by society. Primarily, it frees us, especially children and young people, from ignorance. This is very much so in Ghana and Africa, and for that reason, culture is a theme that cuts right through and across the entire landscape of my work, like highways through the countryside. I use it to free, empower, and enrich, and also to show that even the identities that we call a “self” actually overlap, and I explore this in in various situations in my books.

Finally, I believe that the world really and truly wants us to know it, experience it, and enjoy it as a whole—and this it conveys to us in diverse ways, through diverse inspirations, visions, and talents, and we must learn to listen.

October 23, 2015

Norman, Oklahoma