Kiwi Crime Writing: A Rich Tradition from a Distant Sea

New Zealand is, relatively speaking, a tiny country with a population half the size of New York City and in a location so remote, a commercial flight from Los Angeles takes over fifteen hours to get there. The closest big city, Sydney, is three hours across the almost landless Tasman Sea. Legendary for the beauty of its landscape and the fierce Maori culture that has occupied the islands since the late thirteenth century, Aotearoa, as the Maoris called the north island, had its first European contact in 1642, and its coastline wasn’t mapped extensively until Captain Cook arrived in 1769. After that, immigrants began appropriating the land, and today the ethnic population is about three-quarters European. The travel book cliché is that New Zealand is culturally the “most British” of the former British colonies, and we can see that in the influence of Kiwi writers on that most British of literary genres, the mystery, from the very beginnings of the genre.

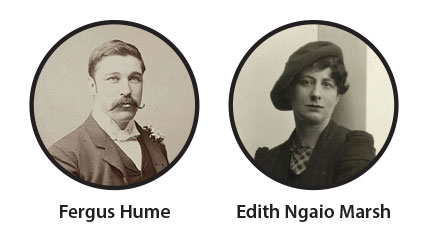

One of the earliest best-selling mysteries in the world was written by Fergus Hume, who is claimed by New Zealand even though he was born in 1859 in the Worcestershire City and County Pauper Lunatic Asylum in England, where his father worked, and only lived in New Zealand from age three to age twenty-five. In 1861, during the Otago gold rush on the south island of New Zealand, his father became superintendent of the Dunedin lunatic asylum. Educated in what is now the Otago Boys’ High School in this remote outpost of the empire, and likely isolated even more by living on the grounds of an asylum, young Fergus must have dreamed of bigger things. Even though Dunedin’s population multiplied fivefold in the 1860s and became New Zealand’s largest city from 1865 to roughly 1900, it was under twenty-five thousand people even then. Hume matriculated to the University of Otago, studied law, and was admitted to the bar in 1883, but the prospect of a steady career as a lawyer was not enough. He wrote poetry and anonymous reviews that were published in the local press and became involved in local theater. He developed a reputation as a dandy, but being a big fish in a small pond was still not enough.

He moved on to Melbourne, Australia, which had a more lively theater culture, but the theater community of Melbourne was basically a closed shop. Hume could not get any of his plays read, let alone produced. Determined to break into writing, he thought perhaps a novel would work for him. He researched what was selling and discovered that the novels of Émile Gaboriau were popular. Edgar Allan Poe is credited with first making the mystery a popular genre, and Poe’s influence on the French was very powerful. Gaboriau’s L’Affaire Lerouge (1866) began a series of pioneering French mysteries drawing from the memoirs of Eugène François Vidocq (as Poe had) and further popularized and developed the crime novel. Gaboriau died in 1873, but the translations inspired Hume to write The Mystery of a Hansom Cab, which, like his plays, no publisher would touch. They had no faith in a book by a colonial, he was told. The complicated story of its publication was recently researched and recounted in Blockbuster! by Lucy Sussex. When Hume had it privately printed in 1886, the book flew off the shelves. British publishers now came hat in hand, but Hume didn’t believe it would be as successful in Britain and America, so he sold his book rights for fifty pounds. The New York Times reported in Hume’s obituary that the book sold half a million copies. He made money on the dramatic version, however, and moved to England, where he wrote mysteries until his death in 1932. Hansom Cab, it is worth noting, preceded the first appearance of Sherlock Holmes by a year, and thus this backwater colonial deserves major credit as one of the most influential creators of the mystery genre.

If Fergus Hume was New Zealand’s Aeschylus of the mystery, assisting in the birth of the form, Dame Edith Ngaio Marsh was clearly the nation’s Sophocles, shaping the classical elements of the form.

If Fergus Hume was New Zealand’s Aeschylus of the mystery, assisting in the birth of the form, Dame Edith Ngaio Marsh was clearly the nation’s Sophocles, shaping the classical elements of the form. Her name is spoken in equal, if not more, reverence to the greatest giants of the Golden Age mystery, the “Queens of Crime”: Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Margery Allingham. Marsh’s first of over thirty novels appeared in 1934, with her last appearing in 1982, the year of her death. While Christie sometimes switched her detectives, using Poirot or Miss Marple or Tommy and Tuppence; Allingham wrote several novels without her upper-class detective Campion; and Sayers ultimately gave up crime writing as an inferior form of literature, Marsh was steady from her first novel until her death in using her detective Roderick Alleyn in all her books. Alleyn is a police inspector, but the novels are more characteristic of the Golden Age than the police procedural that now dominates crime fiction and drama. Alleyn is Oxford educated, a gentleman detective, and a veteran of the Great War. The books have tricky murders of the type Raymond Chandler hated, and most are set in England. Only four novels are set in Marsh’s native New Zealand. Perhaps she was avoiding the publishers’ anticolonial prejudice that Fergus Hume had endured. Though she hated to fly, she was well traveled, using sea voyages to write. Yet she was born and died in Christchurch in the same house she had lived in from age seven. She thought of England as her cultural home, had a distaste for the New Zealand accent, and was said to be unsympathetic to nationalist aspirations.

Like Hume, she was enthusiastically interested in theater, particularly Shakespeare, though she achieved success Hume could only dream of. Marsh wrote an unsuccessful play and acted in repertory for several years in the early 1920s, but her later work as a producer and director stimulated the development of serious theater in New Zealand. The theater at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch (which was ruined by the 2011 earthquake) was named in her honor in 1967, and she directed the first production there. And, yes, her detective was named after Elizabethan actor Edward Alleyn, one of England’s first dramatic “stars,” an actor rich enough to endow the still-operating Dulwich College. Although Marsh was estimated to have sold two million novels at the time of her death in 1982 and is still popular around the world, New Zealand writers often complain she is more remembered there for her contributions to the development of theater.

Nonetheless, the Kiwi tradition of best-selling crime fiction did not weaken with the passing of Ngaio Marsh in 1982. Paul Cleave is one example. Like many writers, Cleave knew that he wanted to write from childhood, and after the sale of his first thrillers, The Cleaner (2006) and The Killing Hour (2007), he gave up his day job as a pawnbroker and sold his house to make his way as a professional writer. His gamble paid off. In his early thirties, he didn’t have to wait long. The Cleaner, the story of a serial killer who is a janitor in the police department of Christchurch, became an international best-seller, particularly in Germany. Sales have exceeded half a million copies globally, and Cleave has followed that success with a novel a year, racking up nominations for a Ned Kelly Award (Australia), the Edgar Allan Poe Award, and others, including New Zealand’s Ngaio Marsh Award for Best Crime Novel, which he won in 2011 for Blood Men. The Marsh Award was only in its second year, having been created by attorney and critic Craig Sisterson, who wanted to stimulate local support for Kiwi crime writers because he felt they were getting more attention abroad than at home. Cleave’s novels are set in Christchurch, a place known for its photogenic qualities, but Cleave has said he creates an alternate reality in which the city is a dark Gotham City as seen in the novels through the eyes of his characters, policeman Theodore Tate and the serial killer janitor Joe Middleton.

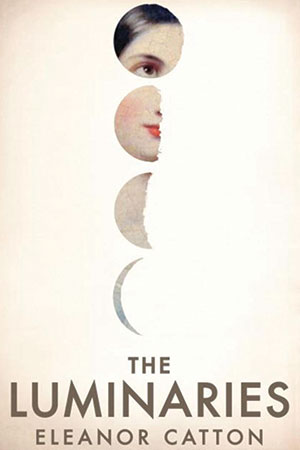

One of the most interesting and unconventional mysteries from New Zealand was published in 2013. The Luminaries was the second novel published by Eleanor Catton, who at age twenty-seven would become the youngest winner of the prestigious Man Booker Prize. Born in Canada, Catton’s father was a New Zealander and a relation of historian Bruce Catton. She lived in Christchurch, attended the University of Canterbury, and after earning a master’s in creative writing at Victoria University of Wellington, published her thesis as her first novel in 2008 and accepted a fellowship at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. With all that promise, what followed was nonetheless astounding. The Luminaries is set in 1866, during the gold rush that Fergus Hume had witnessed, and is written with the kind of twisted and complicated plot of secrets that is common in the earliest forms of the mystery novel with Charles Dickens (who is often said to be the first writer to have a detective character) and his friend Wilkie Collins. Like Dickens (who was usually paid by the word), Catton did not stint on words. The novel runs to 832 pages, the largest ever to win the Man Booker, and filling the pages are an extraordinary variety of characters. The plot—prospector Walter Moody stumbles into a meeting and becomes involved in the solution of unsolved crimes—barely hints at its complexity. Each of the council members is associated with a sign of the zodiac, for example, and other characters are associated with heavenly bodies. Besides taking a nineteenth-century form, the novel simulates the language of the time. While writing this tome, Catton only read books that had been published before 1866 and was influenced by The Brothers Karamazov and Collins’s The Woman in White. She also said she was inspired by long-form television, such as The Sopranos and The Wire, which is often dubbed the newest metamorphosis of the novel.

One of the most interesting and unconventional mysteries from New Zealand was published in 2013. The Luminaries was the second novel published by Eleanor Catton, who at age twenty-seven would become the youngest winner of the prestigious Man Booker Prize. Born in Canada, Catton’s father was a New Zealander and a relation of historian Bruce Catton. She lived in Christchurch, attended the University of Canterbury, and after earning a master’s in creative writing at Victoria University of Wellington, published her thesis as her first novel in 2008 and accepted a fellowship at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. With all that promise, what followed was nonetheless astounding. The Luminaries is set in 1866, during the gold rush that Fergus Hume had witnessed, and is written with the kind of twisted and complicated plot of secrets that is common in the earliest forms of the mystery novel with Charles Dickens (who is often said to be the first writer to have a detective character) and his friend Wilkie Collins. Like Dickens (who was usually paid by the word), Catton did not stint on words. The novel runs to 832 pages, the largest ever to win the Man Booker, and filling the pages are an extraordinary variety of characters. The plot—prospector Walter Moody stumbles into a meeting and becomes involved in the solution of unsolved crimes—barely hints at its complexity. Each of the council members is associated with a sign of the zodiac, for example, and other characters are associated with heavenly bodies. Besides taking a nineteenth-century form, the novel simulates the language of the time. While writing this tome, Catton only read books that had been published before 1866 and was influenced by The Brothers Karamazov and Collins’s The Woman in White. She also said she was inspired by long-form television, such as The Sopranos and The Wire, which is often dubbed the newest metamorphosis of the novel.

The critical reception was so breathless at The Luminaries’ simultaneous old/new novelistic accomplishment that one wonders how Catton can follow it. The crime-writing bar has been set very high on that distant island nation. Kiwi writers like Alix Bosco, Neil Cross, and Vanda Symon are the equals, if not superiors, of crime writers anywhere. We can only anticipate how much higher they may raise the bar.

University of Oklahoma