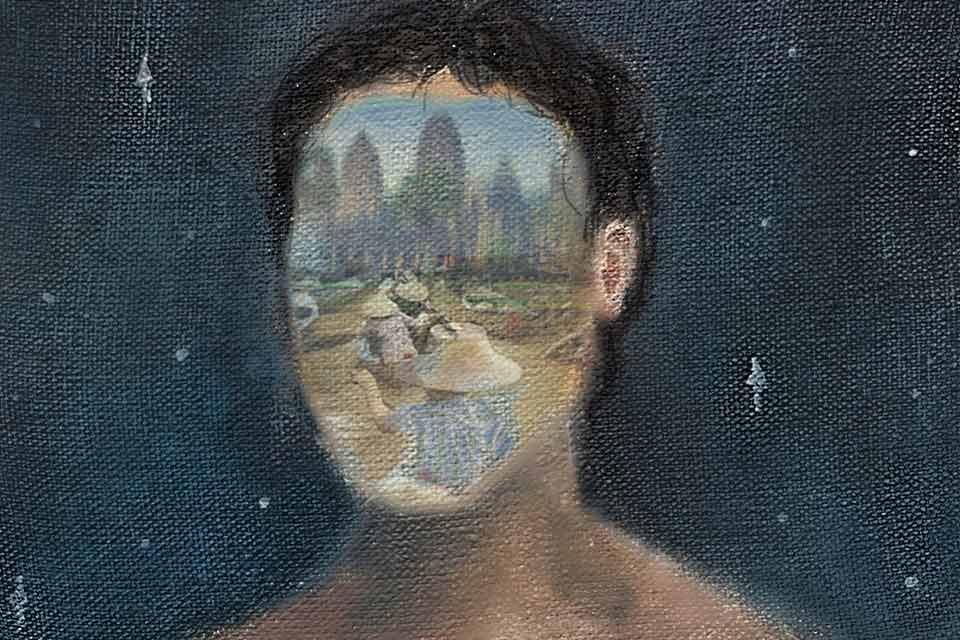

Four Cambodian American Poems

I’ve Been Border-Crossing All My Life

after Anisa Rahim’s “A Russian Hacked My Pinterest Account”

I’m not talking about the sudden packing up of things

a pair of pants, a bag of uncooked rice, gold sewn inside belts

salted fish, soil from mother’s grave, a small statue of Buddha

Not having time to say goodbyes to friends, not knowing if this leaving

would be forever

it was forever

Sitting on Lok-Yeay’s back as my family trekked through jungles,

stepping in small rivers where if you looked to your right

or left

dead bodies & torn-off limbs everywhere

tiny fish feeding on rotten meat

I looked up from the darkness the night sky was turning

the stars were bright clear and real

I could almost pluck them the universe

was alive

And the silence was eternal

the warm presence of ancestors

how deeply comforting

the cosmic ocean

I’m not talking about life in refugee camps

not quite in Thailand, not quite in Cambodia

it was the third space of nothingness

Floating from one camp to another

home was homelessness

home was the longing for what we left behind

home was speaking to ghosts

I’m talking about finding a bird

with broken

wings

Looking for lizards, frogs, snakes, crickets

anything that was alive

imagining they were my father

I’m talking about speaking to the bird as if it were my mother

as I tended to wings

broken

red-stained

I’m not talking about getting on a dinghy

some Thai fishermen used to take us across

the Gulf of Thailand

to Indonesia, our little

boat

almost swallowed by giant waves

I’m talking about seeing a mermaid

in the midst of a storm

while everyone cried-prayed

to Buddha for help

I saw a mermaid floating calmly

in the terrible waves

How to Defeat Pol Pot

Call your children by their true names.

Love. Divine. Angels. My heart.

Be gentle with them.

Speak the truth:

They were born out of love.

These divine creatures.

Tell them the Angkor Empire stood

for six hundred years.

America is half that age.

Read to them Khmer poetry.

Show them Apsaras dancing on temple walls.

Pick up a paintbrush, play an instrument.

Let the soul sing its song.

The Khmer Rouge made angels of us all.

We soared over killing fields

to find home on foreign shores.

Keep memories of the victims in songs and prayers,

in the spoonful of rice we feed our children.

Sing to the moon for what it witnessed.

The Mercy of Memory

My cousin tells me about what he witnessed:

the way they dragged his neighbor by the legs,

how the poor man begged for mercy.

When they didn’t stop, the neighbor looked

up to the sky and sobbed quietly

at the indifference of the universe.

After the neighbor was disappeared

there was nothing left but the hot sun.

The sky was blue and the birds sang

their beautiful songs over rice fields.

The silence of that moment has

haunted my cousin through the years.

As for me, I have no recollections.

No evidence of atrocities I could

document or share in commiseration.

I must have been four or

five when the Khmer Rouge

took over Kampuchea.

I must have seen and heard things.

I must have felt fear when carried

in the night on my grandmother's back.

This is the mercy of memory.

How it opens and closes

certain doors to sustain itself.

Just enough light for the self to

continue, like the memory of love

a grandmother had for her grandson.

The Carrying

I am what is left after the war that orphaned a generation.

And what is left is knowing that what remains is worth

Carrying. The way the earth carried our tired bodies.

How the moon kept still while we crossed jungles,

Leaves whispered prayers and sunlight kept us

Warm. The way Lok-Yeay carried me on her back,

The back that carried the land and fog, the hungry mouths

Of children and grandchildren, the withered body of her

Husband, the grime of a widow who raised seven children

All on her own. The way rivers carried our sorrows.

And how my aunts carried the deaths of their youths

Cradled to their chests like broken dolls.

How we all carried memories of my mother.

How my father carried himself after we had left.

At night in the refugee camp my uncles cradled

Hope that was as real as the belief that

No matter what came before, a life was still a life.

Then they turned to their corners of dirt and wept.