Myth, Memory, and Transcendence in Hélène Cardona’s Dreaming My Animal Selves

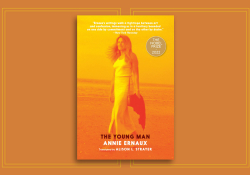

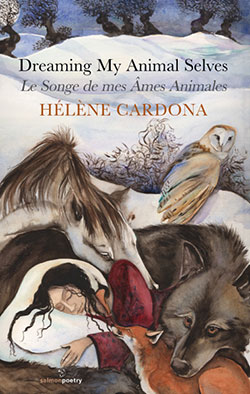

Shortly after my mother died, while napping near an open window of my apartment on Avenue Foch, I felt—or thought I felt—a hand touch mine. It was warm, large, and familiar. Then I heard my mother’s voice and woke up to see a little bird that flew away toward the Bois de Boulogne. This memory came back to me as I read a collection of poetry by Hélène Cardona, Dreaming My Animal Selves / Le Songe de mes Âmes Animales (Salmon Poetry, 2013), for this is a collection of dreams, grieving, memory, and transcendence. As I awakened from this memory of my mother, I read these lines and was consoled for my loss:

Shortly after my mother died, while napping near an open window of my apartment on Avenue Foch, I felt—or thought I felt—a hand touch mine. It was warm, large, and familiar. Then I heard my mother’s voice and woke up to see a little bird that flew away toward the Bois de Boulogne. This memory came back to me as I read a collection of poetry by Hélène Cardona, Dreaming My Animal Selves / Le Songe de mes Âmes Animales (Salmon Poetry, 2013), for this is a collection of dreams, grieving, memory, and transcendence. As I awakened from this memory of my mother, I read these lines and was consoled for my loss:

Consider this, be fortunate, grateful,

consider this, be alive

for the greatest gift is given with death.

There is no end and no beginning,

surrender, surrender, surrender.

I pay with my mother’s death

for the price of my dreams

as I dream the world into being

as I dream new memories

as I dream myself into love falling into you. (“Dreamer” 60)

Considère ceci : sois fortunée, reconnaissante,

considère ceci : sois vivante

car l’ultime cadeau est donné avec la mort.

Il n’y a ni fin ni début,

succombe, succombe, succombe.

Je paie avec la mort de ma mère

le prix de mes rêves

tandis que je rêve la création d’un monde,

tandis que je rêve de nouveaux souvenirs,

tandis que je me rêve d’amour t’inonder. (“Rêveuse” 58)

This bilingual collection is a series of poems to remind us of what gives birth both to the literary imagination and to identity. It reminds us of those people, memories, and desires we carry around within us, often without knowing it, until we sleep, dream, and remember our most precious feelings, memories, and sensations.

Cardona’s poetry reminds us of those people, memories, and desires we carry around within us, often without knowing it, until we sleep, dream, and remember our most precious feelings, memories, and sensations.

This may be why Cardona, too, associates her mother’s loss with the emergence of new love and creativity. In “Dreams like Water,” she

trace[s] patterns in dreams

through beings disguised

undone like particles broken apart

revealing pieces of [herself]. (17)

Pieces reconstructed over time, as she “pursue[s] elusive sleep / in the hope to heal mishaps” looking for one “last chance to anchor [her] boat.”

“Solicited by playful spirits,” in “Isle of the Immortals,” she “part[s] the swelling mist” of the imaginary that “reflects the hidden side of the moon” and of the unconscious/self, to dance with a wizard she sees in the form of a crane, who “spirals down the water tunnel, wings a blur,” whispering to her something I may have said to myself after the dream of my mother’s visitation: “You’re learning to live in two worlds at once.” Both are necessary—the real and the imagined, the one that lies at “the core of the earth” and the one that resides in consciousness. We who experience such imaginings live the life of one who incorporates the spirit of those we lost in aesthetic reminders and little things in nature that spur us on to remember our gifts, and we do this almost effortlessly, as these spirits reside in us in “[t]he way seeds need darkness to germinate” and in “condensed light” that emerges as an effervescence of joy. Traveling through dreamy, mythological, and symbolic landscapes of mind, this joyful reverie is protected, in Cardona’s work, “under the crane’s guidance”: where a spiritual boat “in the clouds reaches the Isle of the Immortals” and makes the “soul resplendent.”

This is the language of transcendence, of mythological and Jungian dream analysis that allows us to perceive parts of the self that are both lost and found in symbolic language. Here is the language of magic, of fairies and spirit animals (especially birds and horses), which embody physical and spiritual grace that reveals special things to the poet—both inner and outer sides of herself returned, after loss, which link her to her ancestors, to the seemingly dead or forgotten, and to the beauty of the creative and intellectual life emerging from lost figures, and thus help her to develop inside.

These figures and dreams serve as spiritual and organic nourishment leading to an inner “floraison” by simply being who they are in her mind: fortifiers of nature, intellect, creativity, and the soul. As she writes in “Peregrine Pantoum,” her “grandmother’s exquisite designs / engineered by elves” help her to “sleep with fervor.” This is not sleep from fatigue nor to ward off illness, but the sleep where “[w]isdom and melancholy build fires,” where “myriad books and soulful dwellings” help the young poetess-to-be to overcome memories of “slippery roads” and “frozen paths.” This is the sleep that reinvigorates and helps one navigate body and soul once more between the real and imaginary, the spirit world and the gravitational field, where memory and forgetting, “mazes of mind,” and “tales of torture” reside, along with certain gods that impose “exiles and travels, forced and chosen.”

One wonders to what extent these travels and forced departures were real or imagined, and neither in sleeping nor in waking can we be certain whether these are imposed from the outside or inside; nor does it matter. We are certain that the poetry which reminds us who we are and where we have been is of utmost importance and brings us back to the root system of soul, psyche, and personality. This spiritual home “[begins] with a dream”; “[t]he dream opens forgotten realms of creation” (“Pathway to Gifts”): the birth of the child that imagines her conception in the “shiver down [her] mother’s / spine” that is congealed in “the melancholy in [her] father’s eyes, / reflecting Lake Geneva” (“From the Heart with Grace”). These signs and forms of unspoken communication were once “indecipherable” to her younger self, but in reflection the poet remembers that these were always part of “a language older than time,” a language completely human, maybe more so than words.

And yet words are so important to this writer. They are not just vehicles of communication but “whimsical metaphoric frontiers” opening up gates to the unknown, beyond the cellular toward the spectral. If they are used at all, they are to be treated as precious gems, each to be chosen, cut, shaped, and set into her design with care, like her poems. For neither Cardona nor her imaginary or mythological worlds are merely shape-shifters; they are “griffons,” “mermaids,” and “chameleons.” She is not merely a tree who remembers her roots, in Spain, Switzerland, or in the creative mind that eschews a “quintessential” and existential “distress,” but she is one rooted in a “jeu d’esprit, glückliche Reise.” She is not a passive recipient of the earth’s gifts and cornucopia, but one who “propels the fervent fragrance / of heliotrope, hyacinth and honeysuckle.” She is a generator of all that is good, which we desire on earth and in the mind.

This is the honey that brings forth sweets for the soul: the consolation of art. This ability to become the jewel-maker of words, the metaphorical honeybee, the generator of dreams and of all life’s eternal joys, is divine. It is the eternal gift of life, for if you find yourself on the road, through forced or chosen departures, it is essential for us all (particularly the artists among us) to imagine that the “[w]ind . . . offers / . . . three cups overflowing / with eternity”—the symbol of fulfillment in Tarot. In Cardona’s universe, as long as the mind and spirit are alive and “on the wing,” the cups are always half-full, and we may hope to be as resilient as she—like the “thistle” that is her surname, “Cardona”; that which dreams and endures the tides, seasonal change, and fickle conditions of life.

That endurance is partnered with a certain perception—one that

find[s] the resonance of [one’s] core

and discover[s] that in dreaming

lies the healing of the earth. In dreaming

we travel to a place where all is forgiven. (22)

That is where we want to be, at least when there is no way to turn back time or the tides, and when nothing more can be said face-to-face. That is when we must surrender to the “Night Messenger” and “[let] the current carry [us],” like the penguin, across the river and say to ourselves, as he does, that “this stream is your life” and “let the river transport me / knowing I’ve entered another world.”

To allow the changes, deaths, removals, and currents that take us along their path, if not to our intended one, is to remind ourselves that we are all mere travelers, not just on earth but in the “corridors of mind,” and that even if we must leave people and possessions, homes and countries, behind, in reaching our soul’s destiny, we inhabit a place (if we are lucky) that can never be lost, for the “heart [is] / a secret tower I inhabit,” writes the poet, like her name that is as eternal and enduring as the “pyramid, antique amulet” is to the Egyptologist and the mummies in pursuit of the afterlife (“Cornucopia”).

The message, to me, is clear. We are to bring that afterlife into the current one, both in connecting with the tides around and within us, and in receiving the information given to us by nature and myth. So when I witness a swan swimming in “concentric circles,” as I often used to in the Bois de Boulogne, I “find the resonance of my core,” and embrace my “animal self” and “raison d’être,” integrating the “insubstantial, chameleon” and painfully “excavated” parts of myself and of my past, into my whole being, “like a talisman from wreckage, [a] resplendent fresco catapulted / beyond whimsical metaphoric frontiers” to be transformed within.

Hélène Cardona has given us a gift with this collection that both the English-speaker and francophone alike can appreciate. Anyone who has grieved the loss of childhood experience, of treasured places far away, or of a loved one close to home can appreciate the sensitivity with which the poet conveys her longing to recapture these losses in art. I find much to appreciate here, and I am relieved to discover that solid ground may be established by embracing all that we are: the dream-life, a connection to nature, memory, and the imaginary. All is forgiven and recalled, all energy becomes light when “I sing this whistling song,” from “the cliffs where the wild ones come” and “look at the other side of the world” from within (“Pathway to Gifts”).