Beyond “Normalcy”: Sayaka Murata’s Life Ceremony

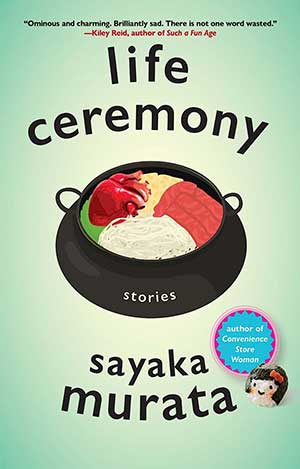

Life Ceremony (Grove Press, 2022) marks the third translation—once again expertly rendered into English by Ginny Tapley Takemori—of recent works by Sayaka Murata (b. 1979) in five years. It differs, however, from both Convenience Store Woman (2016; trans. 2018) and Earthlings (2018; trans. 2020) by being not a novel but a collection of twelve short stories. Many of these stories appear loosely related to others in the collection, although the contours of those relationships are variable: a setting reminiscent of the rural site of an ancestral home found in Earthlings, a gentle thematic connection, a shared personal name, food, or a fascination with the contravention of societal expectations.

Life Ceremony (Grove Press, 2022) marks the third translation—once again expertly rendered into English by Ginny Tapley Takemori—of recent works by Sayaka Murata (b. 1979) in five years. It differs, however, from both Convenience Store Woman (2016; trans. 2018) and Earthlings (2018; trans. 2020) by being not a novel but a collection of twelve short stories. Many of these stories appear loosely related to others in the collection, although the contours of those relationships are variable: a setting reminiscent of the rural site of an ancestral home found in Earthlings, a gentle thematic connection, a shared personal name, food, or a fascination with the contravention of societal expectations.

A few of the stories stand as uniquely independent entities. Recognizing and exploring these overlapping and diverging points provides a gentle texture to the readings that acts to slow one’s pace and focus one’s attention. Murata provides no clue about the mode of these stories. Are they fantasy? An imagined future? Hallucinations? At the end of the day, these concerns are of less import than the broader questions the stories pose about the definition, parameters, and meaning of “normalcy” in a rigid society. Murata effects a critique of the social constructs that seek to confine the unusual and asks us to examine our deeply held beliefs about the value and function of those constructs.

These stories pose broader questions about the definition, parameters, and meaning of “normalcy” in a rigid society.

I shall not provide a synopsis of each of the stories, but there are several that certainly stood out. Two stories merit a quick comment. The fantastical “Lover on the Breeze” offers a vignette of what it means to be in love, to be jealous, and to suffer loss through a ménage à trois among Naoko, her boyfriend Yukio, and a curtain in her bedroom she has named “Puff.” It is hard to find much more here, but even this wisp of a story hews to the broader task of problematizing convention. “A Magnificent Spread” is faintly redolent of Earthlings as it describes the tensions between the differing eating habits of a husband and wife. He enjoys the food of this future world, and she that of the magical city of Dundilas. Although we might imagine a moment of joy when this distance between the couple collapses, the outcome Murata portrays is far less pat. We are yet again forced to consider who benefits most from social norms, and how their violation might play out in an environment where those norms are opaque.

Three other stories are particularly noteworthy. “The Hatchling” is, perhaps, the story most closely aligned with the previous works by Murata that have been translated into English. Her protagonist, Takahashi Haruka, confesses early on that “[s]oon after I started at university, I realized that I didn’t have a personality of my own” (214), immediately alerting us that we are in familiar territory, dealing with someone who does not fit easily into societal norms. Like the protagonist of Convenience Store Woman, Haruka “was just a machine that responded to the community in order to be liked” (221). In point of fact, Murata is asking us to think about the discrete personas we all create that—although certainly not as extreme nor as independent as Haruka’s—enable us to navigate the different circles within which we move. It should come as no surprise, however, to realize that we do not get off the hook that easily. The dénouement makes it clear that managing these personae, “unifying” them as most of us do, comes at a cost, and Haruka is not at all convinced that unification is worth the sacrifice. We are asked, thereby, to consider whether the benefit of conformity is sufficient compensation for the loss of our myriad selves.

The titular “Life Ceremony” was the work that provided me the greatest food for thought, a cheap pun whose relevance becomes clear as soon as we learn that the ceremony in question is a death ritual in which the deceased is turned into a meal and eaten by surviving friends and relatives. This is, in fact, only half the custom because it also requires “procreation [as a] form of social justice” (72). This circle-of-life ceremony is fully completed only when the participants settle down to extroverted fornication inside, outside, on the street, everywhere, leaving large deposits of semen as proof of their success. (Although in a realistic world, semen on the street, lawn, or furniture could hardly be said to mark a successful copulation for the purpose of reproduction!)

Murata probes the question of social mores and taboos, asking whence they come and why they matter.

Although the usual meal is a rather uninspired miso hot pot designed to disguise the gamey taste of human flesh, Mr. Yamamoto, the deceased of interest, was a gourmand. As a result, he left instructions for the preparation of a complex symphony of tastes all built around himself as the main ingredient. Through the acts of eating and sharing the Yamamoto-based food with another, the protagonist is fully integrated into this new normal, so different from the world she remembers of her childhood, as “Yamamoto’s life was fully absorbed into [her] flesh” (110). In this provocative story, Murata probes the question of social mores and taboos, asking whence they come and why they matter. Readers familiar with her earlier works will recognize this as an extension of her broader literary project to problematize the notion of “normal” by inverting, as it were, the relationships that construct that normalcy.

Murata utilizes that same inversion in “A First-Rate Material,” although the focus is not on humans as comestibles but, rather, as the raw material for household items such as furniture, clothing, or wedding rings. This last is of particular relevance because Nana’s fiancé, Naoki, does not share her comfort with this socially sanctioned use of human remains. This disagreement has introduced an element of strife into their prenuptial discussions and opened Nana up to some degree of opprobrium from her friends, who are eagerly anticipating her marriage. Murata drives home her point when Nana responds to Naoki, who is ranting about “using items hacked from dead bodies” (7), with a simple question: “Is using other animals any better” (7)? Any judgment of relative normalcy is socially constructed and consequently open to questioning. Murata also uses this tension between the couple to provide a poignant paean to embracing the moment when you are with someone, taking them where they are, and acknowledging the transience of that time together.

On balance, the collection comprises works of somewhat uneven quality and interest, although the latter is subject to the predilections of each individual reader, of course. That remains a minor quibble, however, for it is hard not to be drawn in by the narratives Murata weaves and the stories’ unusual take on the world. Murata’s relentless questioning of what it means to be human in a world that is not always receptive to difference may be ground she has already trodden, but the familiarity of the path should not blind us to the importance of the journey. How can we live an authentic life without questioning the conventions, morals, and assumptions that structure such a life? Murata may not offer an answer, but she demands that we ask the question.

Bucknell University