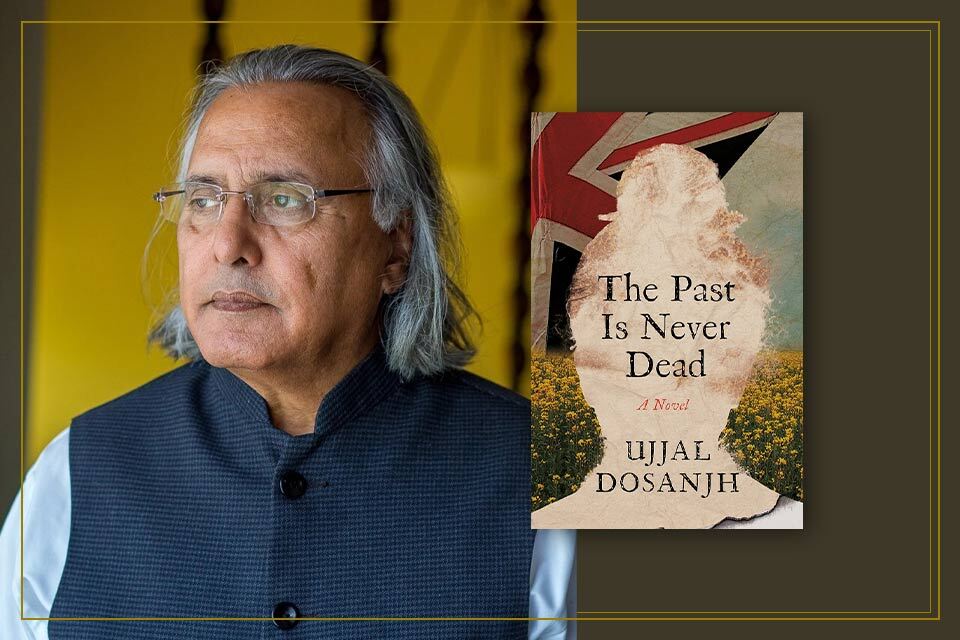

Dalits and Caste Prejudice in Ujjal Dosanjh’s The Past Is Never Dead

There’s currently a surge of new novels in English by Punjabi authors. Interestingly, many of them, written by upper-caste individuals, depict the caste system and its abuses. Ujjal Dosanjh’s The Past Is Never Dead (Speaking Tiger, 2023) can be viewed as part of the same trend. The narrative unfolds around an oppressed Dalit family of three residing in a segregated section of a village near Hoshiarpur, India, detailing their journey to England and subsequent life.

There’s currently a surge of new novels in English by Punjabi authors. Interestingly, many of them, written by upper-caste individuals, depict the caste system and its abuses. Ujjal Dosanjh’s The Past Is Never Dead (Speaking Tiger, 2023) can be viewed as part of the same trend. The narrative unfolds around an oppressed Dalit family of three residing in a segregated section of a village near Hoshiarpur, India, detailing their journey to England and subsequent life.

There’s little new in Dosanjh’s portrayal of caste prejudice in Punjabi and Sikh society, where the dominant caste men exploit Dalit labor, exhibit violence toward Dalit men, and sexually assault Dalit women. However, what sets this novel apart is Dosanjh’s name itself. With a long-standing involvement in Canada’s federal and provincial politics, including a brief term as the premier of British Columbia, Dosanjh is a celebrity within the global Punjabi community. In 2000 I was in Punjab and witnessed how Dosanjh’s rise to the BC premiership thrilled everyone.

Punjabis are immensely proud of their identity and culture. But they, particularly the upper-caste establishment, are also reluctant to address their society’s darker aspects to save face or protect perceived honor. British Indian writer Sunjeev Sahota’s The Year of the Runaways (2015) broke ground as one of the first novels to document caste prejudice within the Punjabi diaspora in the Western (British) world. Thenmozhi Soundararajan, an Indian American Dalit rights activist, has noted anti-Dalit caste segregation and harm among the earliest Punjabi immigrants in the American West Coast and British Columbia during the 1800s in her work The Trauma of Caste (2022).

Back in the 1990s, in India, I watched a wedding video of a prosperous Punjabi-Canadian Dalit family filmed in scenic locations in Vancouver. The Dalit groom, raised in Canada, had fallen in love with a Jat-Sikh girl, and they decided to marry despite objections from the girl’s parents. The video of the lavish wedding ceremony revealed visible tension among the attendees. I was told they feared that the girl’s Jat family could show up with guns and knives for an old-time caste slaughter. It was my first personal realization that caste hatred existed in Western countries.

In 2013 a Punjabi Chamar (caution: the word is also a slur, especially when used by non-Dalits) woman, Kamlesh Ahir, featured in Canada’s mainstream media to talk about caste discrimination. Lately, Western governments are waking up to the prevalence of casteism; Ontario’s human rights commission now recognizes caste discrimination.

Stylistically, Dosanjh often relies on telling rather than showing. Early on, the narrative rushes through the accounts of violence faced by Chamar Udho (Udham Singh). Soon, we read about Udho borrowing money, getting a passport and reaching England as if catching a bus to the next town. A few pages later, we see him return to Punjab after a gap of several years. Also, we learn about the extramarital affair of his young wife, Banti Kaur, in his absence. It’s an odd bit of information, given that the rest of the novel depicts Banti as a very conservative character. Instead of a nuanced fictional narrative with evolving characters, these pages read more like a draft outline presented in bullet points.

Dosanjh does a decent job of exposing the hypocrisies and ironies of the caste system. As the England-returned Udho travels in a Westfalia camper van with his wife and son (Kalu or Kahla Singh), strangers, unaware of their caste, treat them with respect. A Brahmin teashop owner assumes they’re Brahmin, and a Chamar-hating Jat-Sikh travel agent mistakes them as members of his own caste. On the other hand, Banti is portrayed as harboring prejudice against lower-caste Dalits.

Dosanjh does a decent job of exposing the hypocrisies and ironies of the caste system.

Before long, the Dalit family gets into a bunch of quarrels, has trouble with the police, and flees on a taxi, traveling over three hundred kilometers to Delhi’s airport to board a plane to London. The plot unfolds rapidly, somewhat disjointed and B-movie-like.

In 1952 Udho, Banti, and Kalu arrive in Bedford, England, the land of cold weather, toilet paper, orderly shops, predominantly white faces, and racism. To young Kalu, the novel’s protagonist, the Great Ouse appears more like a canal when compared to Punjab’s Satluj River. As he grows up, he suffers caste abuse at school and meets a casteist Brahmin at his workplace. The specter of caste looms over the lives of outcaste immigrants; a Dalit girl is raped by an upper-caste boy, leading to her tragic suicide. Meanwhile, Kalu and a Jat-Sikh girl, Simran, fall in love. The plot thickens toward a somewhat predictable end.

The novel presents the clichéd instances of anti-Dalit abuses one can read about daily in Indian newspapers. Dalit characters appear as stock figures within a well-established and growing literary genre that could be labeled “upper-caste novels about Dalit people.” These novels rarely explore why caste exclusions persist amongst modern, secular, progressive Indians and the so-called anticaste religions.

In Punjab, Dalits make up 32 percent of the population and are primarily landless; 92 percent of rural women laborers, vulnerable to sexual harassment, are Dalit. Casual anti-Dalit violence and murders are a part of life. Such prejudices are carried overseas by immigrants. In 2009 dominant-caste Sikhs shot Dalit Sikhs in Vienna, killing one. In 2023 a British Sikh man was imprisoned for hate speech, glorifying his Jat caste and mentioning rapes of Dalit women. How could this happen in a religious community whose holy book, Guru Granth Sahib, contains verses from the sixteenth-century Saint Ravidas, belonging to the leather-working Chamar caste?

Khushwant Singh, a distinguished writer and scholar of Sikh history, highlighted that despite the teachings of the ten Sikh Gurus against caste, all of them hailed from the Khatri caste, which is generally regarded as the second-highest after Brahmins. Additionally, they tended to arrange marriages for their children within the same caste. We may also note that akin to Hinduism, Sikh scriptures appear to endorse the concept of birth status determined by one’s karma from past lives. It’s not surprising how privileged and exclusionary Sikhs would use the loopholes to establish their supremacy. The truth about caste discrimination is stranger and more unsettling than what Indian-English fiction records.

The truth about caste discrimination is stranger and more unsettling than what Indian-English fiction records.

At times, I struggled through the novel’s uninspiring and scattered plot, accompanied by flat characters. During a scene in a British court, an upper-caste character openly expresses his hate for the rival Dalit party before a judge, “A bloody Chamar . . . untouchable.” The judge wants to make sure he heard it right, “You hated his kind, his caste, as dirty and untouchable?” The man confirms, “Yes.” The witness speaks more toxic and cartoonishly incriminating things. This scene goes on for a few pages as if there’s any doubt about who the judge would support.

After the above court trial and further exchange of abuses, one can guess what will happen next. Amidst much detail, I found a golden nugget. Many years later, Kalu attains the position of professor at a college and is a potential parliamentary candidate for the Labour Party. Jealous of a Dalit’s success, Kalu’s Brahmin academic head issues a damning performance report against him. This kind of upper-caste sabotage in white-collar spaces against Dalits in Western countries has rarely appeared in a novel. Dosanjh also mentions the pervasive casteist abuse Kalu’s son, Angad, goes through at a British school. In other words, the specter of caste isn’t fading with time.

Of late, first-generation Dalit students at American and British universities have reported varieties of microaggressions from upper-caste faculty and students. In turn, several universities have implemented policies against caste discrimination. Good fiction must reveal the truths that news media or the academic world can overlook. On occasion, Dosanjh’s novel succeeds at this task

Kalu’s eventual embrace of his “Chamarhood” is problematic, particularly in a narrative written by a non-Dalit. Embracing or amplifying one’s specific Dalit caste is a controversial practice since, historically, low-paid (and unpaid) menial jobs were imposed upon Dalits, whether through violence or Gandhian religious sermons. The final solution to the caste problem must be a casteless society where surnames would bring neither privilege nor disability. If anything, Kalu should have embraced his Indianhood and British citizenship.

All said, Ujjal Dosanjh has played his part in exposing caste bigotries. In an interview at Simon Fraser University, Dosanjh pointed out that caste bias is also common amongst Punjabi Muslims from Pakistan. As a public demonstration of this reality, the former Pakistani cricketer Wasim Akram used the word “Chamar” in a demeaning manner during a live TV broadcast. Let’s hope the proudest of Punjabis do some soul-searching and repent. Also, they should appear as characters in novels written by Dalits.