Neva Lukić: A Twenty-First-Century Fusion of Orwell and Kharms

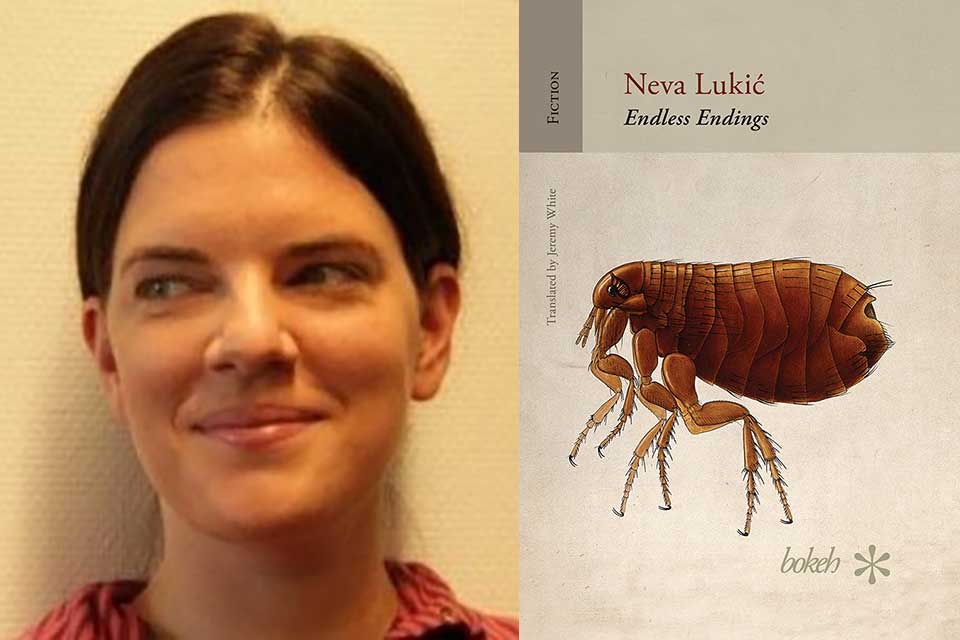

The recent collection of short stories by Neva Lukić, Endless Endings (Bokeh, 2018), originally written in Croatian and translated into English by Jeremy White, was published first in Croatia under a different title: More i zaustavljene priče (HDP, 2016) and then in Serbia (Treći trg, Srebrno drvo, 2018). It is not a debut book but the work of an award-winning and multitalented author who has already published two collections of poems and a collection of short stories, a picture book, and has done screenwriting and directing work.

With other contemporary Croatian fiction writers, such as Zoran Ferić and Ante Tomić, Neva Lukić shares critical humor and irony. Like Tatjana Gromača, she offers a woman’s view of reality. Lukić’s sharp criticism of totalitarian politics can be compared with Daša Drndić’s writing. However, two features, like differentia specifica, make this book by Neva Lukić different from the work of these other authors. They are (1) a deep commitment to language issues and the strong literariness of the text and (2) a critique of totalitarian ideology by using fantasy and paradox, which allow us to describe this writer as the twenty-first-century fusion of Orwell and Kharms. Readers who love wordplay, paradoxes, fantasy, and humor will enjoy this book.

With the first story, “Non-Event,” we immediately enter the poetic rhythm of its syntax, in which Lukić plays with paradoxes. As stories unfold, bold figures of speech multiply. It becomes evident that changes in the strategy of the text reflect her need to reach reality’s essence by playing with words. Unfortunately, some of this linguistic and narrative variety is lost in translation. The opening stories—“The Universe,” “Pandora’s Box,” “Circular Paths,” and “Socks”—help readers understand her relationship with language, its potential, and the purpose of its existence. Most importantly, they brilliantly unmask the ideology of a closed society and its individuals.

Lukić’s stories brilliantly unmask the ideology of a closed society and its individuals

In her Orwellian story “Circular Paths,” Lukić questions the nature of ideology and its manipulations. The story starts out as a fairy tale: “One day, the people of the country came to decide that they were bothered by the fact that not all people were the same height.” Since “their bodies were so perfidiously conspiring against the state,” the state decides to put things in order by enclosing adults in “a firm wooden frame around them during puberty—fixed at one hundred and fifty five centimetres—which would be impossible for their bodies to grow out of” (37). Thus, long before they die, people live in coffins where they can “only strive downward” (38). Even their own children cannot help them, despite trying to stop the adults’ madness. The subjugation becomes normalized: to have a horizontal back means not to have aspirations, not to have goals, to constantly crawl in circles.

Rebellion against the ideology of uniformity develops in the story “Socks,” which starts by transforming a metaphor into a synecdoche—namely, by transforming the life of the word “a pair” by splitting its parts. If a young woman and man start out living harmoniously together as a couple, over time they slowly grow apart by noticing their differences (e.g., her pairing of different socks, or his opposition to the mismatching of socks). “Socks were the prologue to everything public, everything that didn’t happen at home. Straight away, left or right, party orientation, politics . . . the military . . . up and down!” (51). The girl then starts to realize that freedom, which should be the basis of human life, becomes the accused monster of hatred, conflict, and irreconcilable warfare. “I was a destructive, chaotic force, he claimed. I was like the wind and like an earthquake, except after me, the earth was not renewed. I was an eternal dark age of chaos, and if I really wanted to, I would have already paired those bloody socks” (53). All these opposites that make up humanity become undesirable. They have to be reshaped, they necessarily have to become “the promotion of some false reality” (54). Her longing for the two of them to live as a pair of important, essential, and complementary differences becomes more and more unreachable. Like mismatched socks, the two of them “had started to live like this, unpaired and circular,” like some “tragicomic version of Cinderella,” until her left foot remains both without him and without the sock, “bare and abandoned“ (55, 56).

Subjugation becomes normalized: to have a horizontal back means not to have aspirations, not to have goals, to constantly crawl in circles

In the story “The Universe,” instead of describing a house by visual poetry, Lukić puts more emphasis on the interplay between the words “house” and “humanity” in order to remind us that “people did not create languages—languages created people” (20). As she explains in the story “Skysilk,” “Symbolism had become reality, while reality was symbolically unfolding somewhere else” (24). In the stories “Lines” and “The Dark Side of the Story,” Lukić often employs the interplay of words and the symbolism of drawings.

Lukić loves to create new words. Besides the word “skycoon” (26), which describes a man who has become incarnate in a cocoon, into the impossibility of change, she also invents the word “subaphor” (32), that is, a metaphor that signifies low growth along the floor.

Given her chosen topics, it is quite understandable that birds are a common theme in Lukić’s stories. If the paradoxes in the stories “A Story Written in Sound” and “A Bloodless Story” are necessary to counterbalance absurdities, ambivalence, and anomalies, the birds and their ability to fly are the constant symbol of a higher state of mind. Existing between earth and sky, birds symbolize the openness of communication, the freedom of observation, of questioning, dreaming, and, above all, moving. Neva Lukić opens to the reader this important world of freedom, the existence of a wider space where language is the essential point of resistance to tyranny.

Alfa BK University