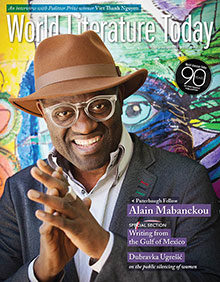

How to Become Globalized Without Losing Your Mind: A Conversation with Alain Mabanckou

During his visit to the University of Oklahoma in April, Alain Mabanckou sat down with Rokiatou Soumaré—a graduate student in OU’s Department of Modern Languages, Literatures, and Linguistics—to discuss his work. Their public conversation, in front of a packed audience, has been adapted and abridged below.

Rokiatou Soumaré: My first question relates to your recent sojourn in France, where you were the first writer to hold the Chaire de Création Artistique at the Collège de France. Could you share your experience with us?

Alain Mabanckou: My experience at the Collège de France is different from what I’ve been teaching so far because you have to teach in front of eight hundred people, gathered in an auditorium, and then you have people in another room who are watching you on a screen. It’s the first time for me to teach in France, after teaching in the United States for fourteen years. And for the first time since the sixteenth century, the Collège de France decided to sponsor a lecture on African literature. So the class is full of Africans, young students, because anybody can come to the Collège. So the challenge for me is to speak to the specialists and nonspecialists alike, so it’s not that easy: you have to be specific at the same time you are trying to explain the first lesson to someone who perhaps never heard about Aimé Césaire, Édouard Glissant, or René Maran.

RS: Hopefully this will open new doors for African writers. Your first lecture at the Collège de France was entitled “Lettres noires: des ténèbres à la Lumière” (Black Literature: From Darkness to Light). Could you summarize it for us?

AM: In that lesson, I try to explain how French literature in the nineteenth or even in the sixteenth century treated African literature or Africa like the continent of darkness, as if we couldn’t speak, couldn’t think. I explain that we weren’t in darkness, however. It was maybe the ignorance of France that made people think Africa was the continent of darkness, which was a reference to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. At the same time, I try to explain how African people did their best to escape from these prejudices in order to create another kind of literature in which they were trying to demonstrate what Africa was; they wanted to show that we had culture even before the white man came to Africa, so our history didn’t begin with colonization. We had great empires in Mali and Ghana, and people forget that the empire of Ghana was twice as big as the empire of Charlemagne in France. So the darkness was on the side of Europe, not on the side of Africa.

So it’s tough to explain that idea at the Collège de France, in the shadow of Barthes or Foucault or Eco, who were teaching European literature. It was for me a way to tell how we came from that kind of darkness and we were trying to learn European literature in order to create our own literature, which René Maran did so powerfully with his novel Batouala (1922). We have a lot of writers like Mongo Beti, Camara Laye, and so on. I gave that lecture in order to explain even to someone who didn’t know anything about African literature that they need to read us even to understand French literature because African people read French literature. That way we have this kind of step forward compared to French perceptions of African literature.

RS: Let’s talk about your novels now. Many of them include intertextual references, such as Broken Glass or African Psycho, to name a few. What motivated your choice to use so many references to other literary works?

AM: I began to write Broken Glass when I was teaching at the University of Michigan—maybe I was feeling bored because of the snow. I was surrounded by a lot of books I was reading at the time, and it crossed my mind: what if I put all my books inside one book so that if they all burn, my books will survive. It was at the same time a game and also a pleasure for me to create a story in which the books are talking among themselves. But it remains a book about Africa and how a human being is trying to face his fate, to struggle, to maybe seek his freedom through the culture. It remains for me one of the books I was most excited about writing—I felt like I was trying to define what I would write later on.

RS: So the references go beyond francophone African literature and even beyond literature written in French?

AM: Yes. I’m glad you said that because French people think that it’s full of French literary references, but you have Latin American, Italian, French, and Russian, García Márquez and Dostoyevsky, you even have The Catcher in the Rye.

RS: On the twentieth anniversary of James Baldwin’s death, you wrote Letter to Jimmy in his honor. How did you come across Baldwin’s work, and why did you decide to dedicate an entire book to him?

AM: When I arrived in Michigan I couldn’t speak a single word of English, so I thought the best approach was to read books in English. Baldwin seemed to me one of the best writers to read in order to achieve that goal, so I began with Giovanni’s Room and then read all his nonfiction books. I was also teaching Baldwin in the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies. The connection between Baldwin and Paris interested me, because Baldwin lived in France until his death. As I was reading, I said to myself, I’m going to try to write a letter to James Baldwin in order to explain how he is still in our lives even if he is no longer with us. When I sent it to my publisher, they were celebrating the anniversary of his death at the time. The book was released in 2007, and I was surprised by its success. Even Gallimard decided to reprint all of Baldwin’s novels, and I was glad to see that such a powerful novelist was being read by French people again. It was my small contribution to bring Baldwin back to the attention of the French reading public.

RS: Who would you consider to be your literary brothers or sisters today? Who are the writers with whom you share a common vision?

AM: Besides Baldwin, I would also mention Sony Labou Tansi, because I was happy to write a foreword to his most recent book, L’État honteux (Eng. The Shameful State, 2015). I met Tansi a lot of times when I was young—I went to see him in Brazzaville and asked him if he could help me become a writer. At the time I was writing poetry; he said to me, If you keep on writing poetry you’re not going to find a publisher, nobody is going to read you. At the time I thought that I couldn’t write a novel. I couldn’t envision writing three hundred pages. In poetry, silence is more important than what you have to say. If you just put the letter “A,” people are going to write a dissertation about that page: why did you mean “A” . . . ?

I also have the same kind of admiration for Gabriel García Márquez, who taught me how it might be possible to write about the Congolese landscape and dictatorship. I have also admired poets like Tchicaya U Tam’si from the Congo and Tati Loutard. In French literature, I like reading Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Albert Camus. Among the Italian writers, I like Giacomo Leopardi. In the United States, I admire Faulkner (The Sound and the Fury) and Hemingway (The Old Man and the Sea). Even in Asia, I’ve been reading Yasunari Kawabata and Kenzaburō Ōe, so my literary family is very diverse. I’m not an African writer who is just reading African literature because I don’t like only using what I have. I need to seek something new, something that can shake me in order to write something original, which is not only African. I think that the best way to deserve the freedom of writing is to explore new writers, new literature. I still have a lot to read—Arabic literature, Indian literature—so I know that I have a lot to find in order to have a big and diverse family.

My literary family is very diverse. I’m not an African writer who is just reading African literature because I don’t like only using what I have. I need to seek something new, something that can shake me in order to write something original, which is not only African.

RS: Lumières de Pointe-Noire (Eng. The Lights of Pointe-Noire, 2015) deals with your return to Congo after a long absence. It has an autobiographical component and offers readers flashbacks from your childhood. It also includes pictures of your family members and yourself. What sets The Lights of Pointe-Noire apart from your other works?

AM: I think that I gave Lights of Pointe-Noire to my readers to help them understand where I came from, why I became a writer, and my emotional attachment to Pointe-Noire. The Lights of Pointe-Noire is my personal Cahier d’un retour au pays natal. Reading the book, you can feel like you have already read all my books: like Tomorrow I Will Be Twenty, like Broken Glass with the people in the bar, like Memoirs of a Porcupine because of the belief systems or cosmogony. It also deals with all the people who disappeared or who are still there and the fact that when you live abroad for a while, coming back to the country is a struggle. You are not Congolese anymore, you are a stranger, so they are going to consider you a stranger. After my return, for the first two weeks people were happy, but beginning with the third week they were asking me, When are you going back? Because they didn’t want me to stay. If you stay in the country you left for twenty years, they’re going to think that you returned as a failure. So they say, Go back to America so we can be proud to explain to people that our native son is living in the United States. . . .

RS: Let’s talk about identity. Can you give us your take on the notion of identity?

AM: The way I see it, identity is something you cannot define because it’s always changing. Living in France helped me understand what identity is when I am in the United States. In France, French people will consider me African, but when I meet them here in the United States, seeing me speaking French, they are going to say, “Thank God someone is speaking French,” and they are going to call me a French guy. But back in France, they will think of me as someone who is speaking French with an accent, an African accent, etc. So identity changes if you move from here to there. At the same time, I think that we need to add other cultures to our culture in order to become globalized without losing your mind. Identity doesn’t mean that you have to erase your own mind or erase your own beliefs in order to adopt another one. You have to keep yours but remain open in order to receive what is most helpful in achieving your own goal. In French politics, identity is very complicated because they want everybody to be like white people. I don’t want to be just a white man or just a black man. I need to be a kind of mixture in which Congo is part of me, France is part of me, along with my American experience and maybe, tomorrow, my Asian experience. That addition is very important to me.

RS: So what is your stance on littérature engagée?

AM: When you are writing a novel, you are always taking part in a discussion about society. Even if you are talking about flowers or snow, it’s a kind of engagement. In engaged literature, you are trying to explain to people how the world is beautiful, how the flower deserves to be respected, how the snow is great if you don’t see it for ten years, so that’s a kind of hope you can share with people. Sometimes people think that engagement is just wanting to fight, to struggle. No. Engagement is not just about struggle. Even being in love, you need to understand how to respect others. You need to spread a kind of song that is going to help people find happiness, so I’m still convinced that engagement is everywhere in literature, even where people don’t always see it.

April 2016

Editorial note: Read a review of Alain Mabanckou’s The Lights of Pointe-Noire in the September 2016 book reviews.