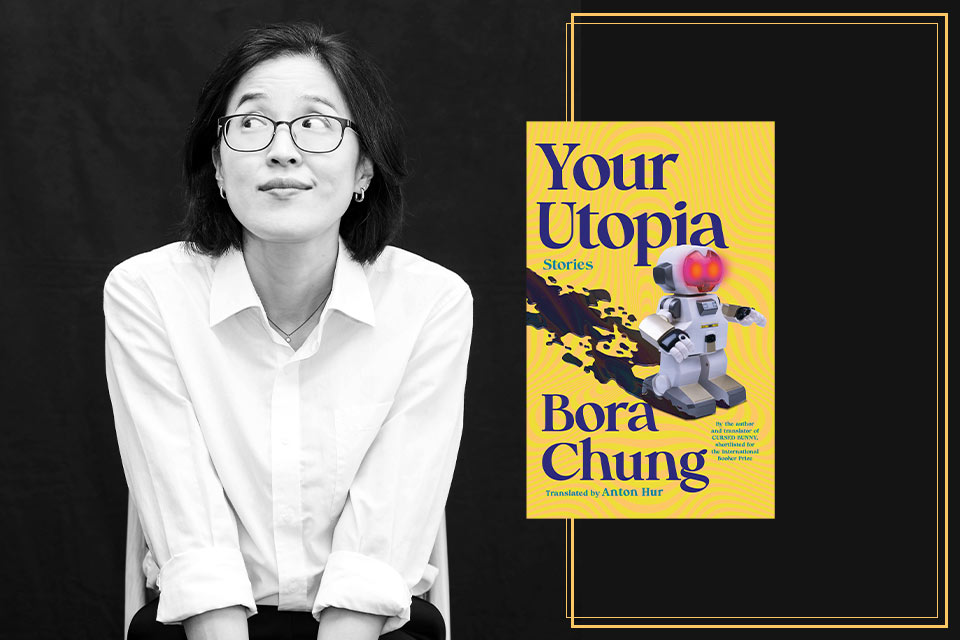

8 Questions for Bora Chung

The author-translator duo shortlisted for the 2022 International Booker Prize for Cursed Bunny have a new collection of stories, published in February. Author Bora Chung’s Your Utopia, translated by Anton Hur, is a collection of eight wonderfully strange, perfectly paced, sometimes even funny stories where things aren’t quite what they initially seem. Halfway through, I knew I needed to read Cursed Bunny.

Q

There are some elements of horror in these stories as well as science fiction and speculative fiction. How would you describe them?

A

Your Utopia as a collection was intended as a book of science fiction. And there have to be elements of horror because we humans do not understand the universe and do not even understand technology created by humans. What we don’t understand will always seem a bit scary.

Q

In another interview, you said that the unifying theme of Cursed Bunny is revenge, which wasn’t something you planned. Not that there needs to be, but is there a unifying theme among the eight stories in Your Utopia?

A

I initially thought the overarching theme was interaction: among humans, between humans and machines, among machines, etc. But I also heard a lot of questions and comments about what it means to be human, so my readers think the theme is humanness. And my readers are always right.

Q

Something about your style that I particularly love is your use of single-sentence paragraphs to create a mic-drop effect, both throughout your stories and, especially, in that final line of “The End of the Voyage.” It’s something I’d like to see more of in writing everywhere. How did you develop this style?

A

I spent a year in Kraków, Poland, on a language program. I had to do a lot of writing in Polish. Mind you, Polish grammar is a complex web of confusion, and nobody can get it absolutely, 100 percent, completely right. So, I tried to write in short sentences, only using the grammatical structures I was sure about. This approach does not help with expanding one’s language skills, but sometimes I ended up with a nice, short sentence that very effectively summarized what I wanted to say. I don’t recommend learning Polish (not good for mental health), but I do have fun experimenting with sentence length.

Q

The protagonists of some stories are AI characters. For instance, one of the stories has as its protagonist-narrator an AI elevator who develops tender feelings for an elderly resident. AI is a heated topic—whether to fear it, embrace it, or find a regulated compromise. How do you view AI?

A

AI learns from humans. The farther artificial intelligences develop, the more humanlike they will become. I expect them to hate and love and discriminate and empathize like us.

Q

I read your new collection right after reading an advance of another new Korean novel, Welcome to the Hyunam-Dong Bookshop, by Hwang Bo-Reum and translated by Shanna Tan, which incorporates the concerns of workers who lack permanent status. Reading your author’s note and the first story in the new collection, “The Center for Immortality Research,” I see that you are passionate about workplace precarity and safety. These are universal issues, of course, but is South Korea at a particular labor crossroads?

A

I worked as an adjunct professor for twelve years, from 2010 until the end of 2021. Before 2019, universities in Korea could hire adjunct professors by the semester, not by the academic year. So I was fired every four months. It was customary for full professors to exploit adjuncts, because they could. I joined the adjuncts’ labor union in 2015 and was active in 2018 to get the Higher Education Bill enacted. I can’t say about South Korea as a whole, but for me it was clear that all my credentials and qualifications meant nothing when it came to job security. As a teacher, I honestly could not tell my students that hard work and good education would do them any good in life. It was painful.

Q

Who are the writers you’re most excited about reading at the moment?

A

Stanisław Lem, the Polish SF writer and probably one of the greatest writers of our time. I am currently translating him. Also Hajin Lee, a fellow Korean writer, is publishing her first full-length novel. I am so very looking forward to it! She’s not translated into English yet, but I hope someday she will be.

Q

What do your favorite stories do?

A

Kill bad people. Sometimes they eat each other, and that’s quite exciting too.

Q

What trends in culture have most recently captured your attention?

A

Anton Hur once mentioned “K-Healing” as a genre: stories and content that comfort the reader/viewer and make you feel good. This includes the aforementioned Welcome to the Hyunam-Dong Bookshop. I happen to be an avid fan of Queer Eye and all the English-language cooking and baking shows. So it’s probably not just Korea, but “K-Healing” is definitely emerging as a genre with its own set of clear and well-defined characteristics. I’m worried that I might be too violent at heart to follow this trend, but I believe we all need some solace to survive in this world.

Bora Chung is the author of three novels and three collections of short stories, including the International Booker Prize–shortlisted Cursed Bunny. She has an MA in European and Russian studies from Yale University and a PhD in Slavic literature from Indiana University. She has taught Russian language and literature and science fiction at Yonsei University and translates modern literary works from Russian and Polish into Korean.