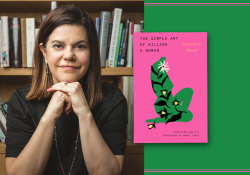

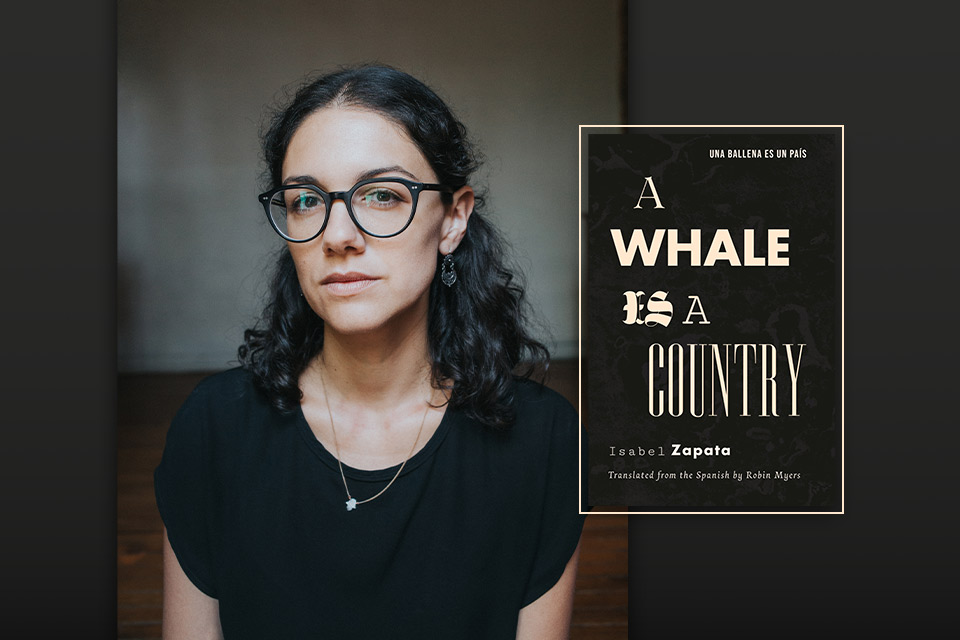

8 Questions for Isabel Zapata

In March, Fonograf Editions published Isabel Zapata’s new bilingual collection, A Whale Is a Country, translated by Robin Myers. Animals appear throughout these poems and hybrid pieces, where we are asked to stop and intently focus on the whale, the mole, the giant tortoise, a defiant rat. Not merely metaphors, in Zapata’s collection of poems, animals are concrete, fully drawn fellow beings, and we are invited to see them in new ways.

In March, Fonograf Editions published Isabel Zapata’s new bilingual collection, A Whale Is a Country, translated by Robin Myers. Animals appear throughout these poems and hybrid pieces, where we are asked to stop and intently focus on the whale, the mole, the giant tortoise, a defiant rat. Not merely metaphors, in Zapata’s collection of poems, animals are concrete, fully drawn fellow beings, and we are invited to see them in new ways.

Q

In your prologue, you write about literature building bridges of empathy. Can you recall a piece of literature or a film that expanded your empathy in some area?

A

This could be a really long list, but one example comes to mind because it’s both an essay and a documentary: Heart of a Dog, by visual artist and composer Laurie Anderson. In this piece, Anderson reflects on the life and death of her dog Lolabelle, while also speaking about grief, Tibetan Buddhism, and reincarnation. I can’t think of a more powerful elegy, and it stressed for me that an animal’s presence (which means, necessarily, its absence) can touch our existence as human beings in unforeseen and profound ways.

Q

Why don’t humans, in general, have more empathy for other species?

A

Western civilization is founded on the belief that human beings are at the top of the scale naturae, or scale of nature: a continuous hierarchy of all living things, arranged in order of “perfection.” We have been taught that other creatures are made for us, and so our relationship with them has always been a utilitarian one. Building empathy with a creature that one considers a utility is very hard, so the first step, I think, is to question our place in the world in relation to them.

The first step, I think, is to question our place in the world in relation to other species.

Q

You also write about Mary Oliver—one of the poets who has had the greatest effect on me—and all that she has taught you, not about how to be a poet but about how to live. What other teachers have you had?

A

Oh, this is a great question. One of the reasons why I love books is because I have found companionship in them—meaning that I can learn from them as I would learn from a friend or teacher in the flesh. I have also learned from Montaigne, from Szymborska, from Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, from José Watanabe . . .

Q

Where do you go to spend time with other species?

A

I have always lived with dogs and continue to do so. Sharing space with another kind of creature is delightful and challenging and comforting, and I would never give that up. There are other species around, too: spiders and ants inside my house; rats, squirrels, and birds outdoors, among others. I live in vv City, so the opportunities to spend time with wilder creatures are scarce, but I sometimes go to the Desierto de los Leones, a national park forty minutes outside the city, to walk and breathe.

Q

In “Language Lessons,” we move through facts about Koko, the Western lowland gorilla who learned sign language. I was struck by how well this piece illustrates how the selection and arrangement of facts affect a story’s telling, a valuable lesson for law students as well as poets. How did you go about constructing this six-page portrait of Koko’s life?

A

This is a peculiar text in the book, because it’s built out of Francine “Penny” Patterson’s real accounts of the years she spent training Koko. I read them in National Geographic, and I felt from the start that there was a poetic seed planted in the scientific language she uses in her writing. I’m very interested in the issue of where poetry “lives,” how something gets turned into poetry, how we can use and change certain informational texts to have a different impact on the reader.

I’m very interested in the issue of where poetry “lives,” how something gets turned into poetry.

Q

Another poet would likely talk more about form, but I was struck by the amount of research you’ve done on animals. What is something surprising you learned while working on this collection?

A

This may sound trite, but when you read about animals, it becomes obvious that the natural world has created more unbelievable creatures than any we could ever dream of. People always say that reality is stranger than fiction, and I don’t think there’s any context in which this expression is clearer.

Q

Who are the writers currently sustaining you?

A

I have been reading books about dogs, because I’ve spent the last few years working on a novel in which a dog is one of the main characters. During this time, I’ve enjoyed exploring authors who portray this relationship (Virginia Woolf, J. R. Ackerley, Sigrid Nunez, Jack London, and Pilar Quintana, among many others) and looking for the points in common, the tensions. This sustained me through the most difficult parts of the pandemic. At the moment I’m reading Brian Dillon’s book on the essay, and I’m always on the lookout for books on motherhood, which never fail to make me feel less alone.

Q

Fill in the blank: what the world needs now is _____.

A

More people doubting their convictions.

Isabel Zapata is a Mexico City–born writer and editor. She is the author of the poetry books Las noches son así (2018), Una ballena es un país (2019), and A Whale Is a Country (2024) as well as the bilingual essay collection Alberca vacía / Empty Pool (2019, trans. Robin Myers), the book-length essay In Vitro (2023, trans. Robin Myers), and the novel Troika (2024). WLT published her essay “And Make It Last, and Give It Space,” translated by Robin Myers, in July 2020.