Once

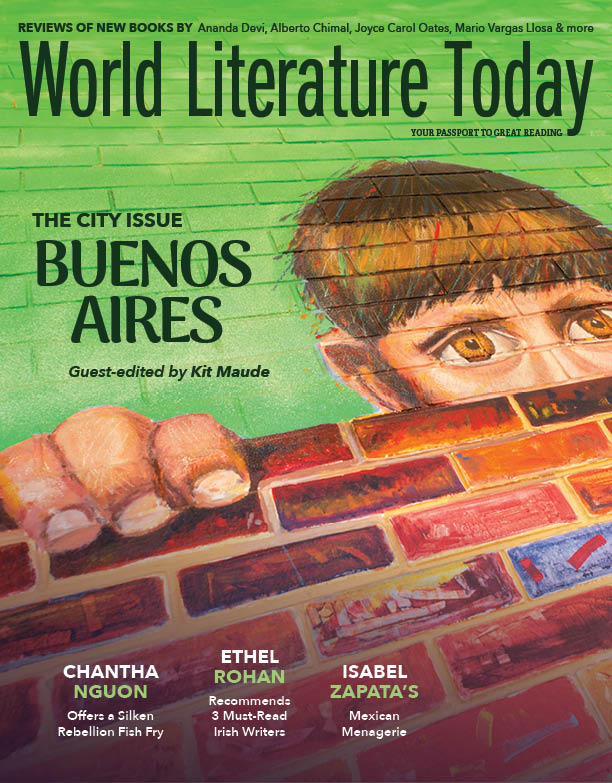

Visiting the Jewish neighborhood of Once, a writer finds herself caught between a desire to escape the internet and a need to connect as she reflects on an essay by Marcelo Cohen and encounters unending visual stimuli.

I’ve been in Buenos Aires, the city where I was born, for three months. Today I am headed to the Jewish neighborhood of Once—which literally means “eleven,” after the 11th of September rebellion in 1852—to pay a writer the grant money I owe them for having read, butchered, and praised my novel. This is called a clínica: a surgical workshop where young writers submit themselves to the opinions of older, more established writers, sometimes to the detriment of their self-esteem. The writer and I only met online while working together on my small internet novel, and I was pleasantly surprised to find out that he lives in one of my favorite areas of town. Once is located at the center of the city, near a number of old downtown monuments and landmarks, and immediately reminds me of an essay by the late Marcelo Cohen, one of the great Jewish Argentine writers of my time. In it, Cohen goes to the optometrist and starts recalling everything that his eye can register, a risky game to play in Once, where visual stimuli are hyperabundant and most of the population is rather myopic.

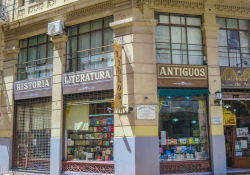

Knowing that I’ll fail, I try to play the Cohen game. The neighborhood has narrow streets, often interrupted by Peruvian, Orthodox Jewish, and Senegalese merchants trying to bulk-sell fake sneakers and small, used electronics. I take a cab and try to get ahead for a few blocks, although a traffic jam (which started around 1972) stops our car in front of a Jewish school. I see a group of religious kids playing at the door, waiting to be picked up, and I try to take a photo of the one I judge to be the most charming. He makes faces at my camera and then goes on to alert his friends. They all start posing in front of the taxi, trying to get onto my Instagram, too. They dance and wave hello. The cab moves on a little, but they continue to make faces from a distance. I try to count the number of times my phone distracts me, even though it has no internet connection.

A few more blocks render the cab futile, so I get out and walk. I see a few Orthodox women and men, and many girls who look like they just left the community—their off-the-derekh knees showing after having exited religious life. Now they walk around Buenos Aires like tourists, the way I do, negotiating their sense of belonging and lack thereof. I keep walking and realize that I have no way of communicating with the writer, since his buzzer doesn’t work and I can’t send him text messages. No one uses their buzzer anymore, I think; they started to break down or the bronze fittings were stolen for scrap, and, in a ruined, internet-dominated economy, no one bothers to fix them. I realize that my mission parameters have changed, and I am now forced to look for Wi-Fi to communicate with him.

I keep walking through shops where they sell electronics, party goods, fabrics, household wares, Peppa Pig paraphernalia, soccer jerseys and towels printed with Messi’s face, shoes, and tiny Christmas lights. Once is at its best in this joyful, kitschy disarray, where sellers try to tempt me with international adapters, counterfeit or stolen phones, vitamins and magic creams, sweetened nuts and seeds, balloons for quinceañeras, bar mitzvahs, divorces. I attempt to ask for Wi-Fi in humiliating ways, dodge mothers helping their kids select their stationery for the coming school year in the hopes of saving a buck. I look for a Starbucks, or a McDonald’s, but there is none. I envy the proud owners of flip phones and Nokia 1100s, pass the Litvak Temple, and wonder whether I should squeeze myself in. Back on the street, merchants yell and ogle in ways that make me walk faster and evade more and more people until I almost crash into a woman selling churros. I try to find a coffee shop, and then I realize I can’t play the Cohen game fully because Cohen existed in a parallel reality, when there were no smartphones and buzzers worked, when you could afford to pay your optometrist and nobody was wired into the stratosphere. I cannot play the Cohen game because the experience of the city has been fundamentally changed by the need for data, for Wi-Fi, and for distractions, because cab drivers now use their GPS to an alarming degree and people have forgotten the names of streets and train stations. Mainly, I can’t play the Cohen game because, even when I attempt to distance myself from the internet, the internet comes back to haunt me.

I can’t play the Cohen game fully because Cohen existed in a parallel reality, when there were no smartphones and buzzers worked, when you could afford to pay your optometrist and nobody was wired into the stratosphere.

I resign myself to the impossibility of finding a coffee shop (who would stop for a coffee in Once?) and walk to the subway station. I pay the equivalent of five American cents to enter. I move past a Senegalese family screaming in French, who look as though they arrived recently—for they walk slowly. I find a small nook by a memorial for the AMIA attacks, where a broken touchscreen promises to tell the story of the car bombing that shattered the central Jewish community building. I squat next to the faces of victims—I know some of their names, some of their families—and plug into the city’s network. While I try to message the writer, I hear an old Bolivian woman ask her son what this installation is about, and he says it’s because of the desaparecidos, the murdered militants and activists during the 1970s dictatorship. I don’t correct them; I think of AMIA’s victims as having disappeared as well. Then I send two messages: one to my husband, alerting him where I am, and one to the writer.

I calculate that it will take me two minutes to walk back to his apartment, so I wait for the double tick on WhatsApp to show up and rush back upstairs. I dodge kids in yarmulkes and furious bicycle couriers, my feet are killing me, and there are trucks trying to unload their cargo while blocking entire avenues. I try to imitate their rage and walk even faster, until I see the writer waiting for me at his door in a decrepit Art Deco building, in the middle of this maddening neighborhood. I pay him twenty-two dollars, which is a lot of money in Buenos Aires, and he says nothing. He stands still, thanking me with his eyes, and proves himself to be as mysterious in person as he was online.

I don’t know what I expected from the encounter, but I return home feeling sad and slightly lobotomized.

I don’t know what I expected from the encounter, but I return home feeling sad and slightly lobotomized. Disconnected from the writer, from my novel, from the internet, and from Once. I am as angry as the neighborhood and just a tiny bit dissatisfied. I realize I no longer live in Cohen’s era and make a promise to myself to visit him in the British Cemetery across town. On the way back, I try to get on the city’s Wi-Fi distractedly, cross Corrientes Avenue at a red light, and get yelled at one more time.

Buenos Aires