The Aura and Eccentricity of Bibliomania in Buenos Aires

Take a whirling tour of Buenos Aires’s secondhand bookstores and meet an array of eccentric reader types with porteño writer Matías Serra Bradford.

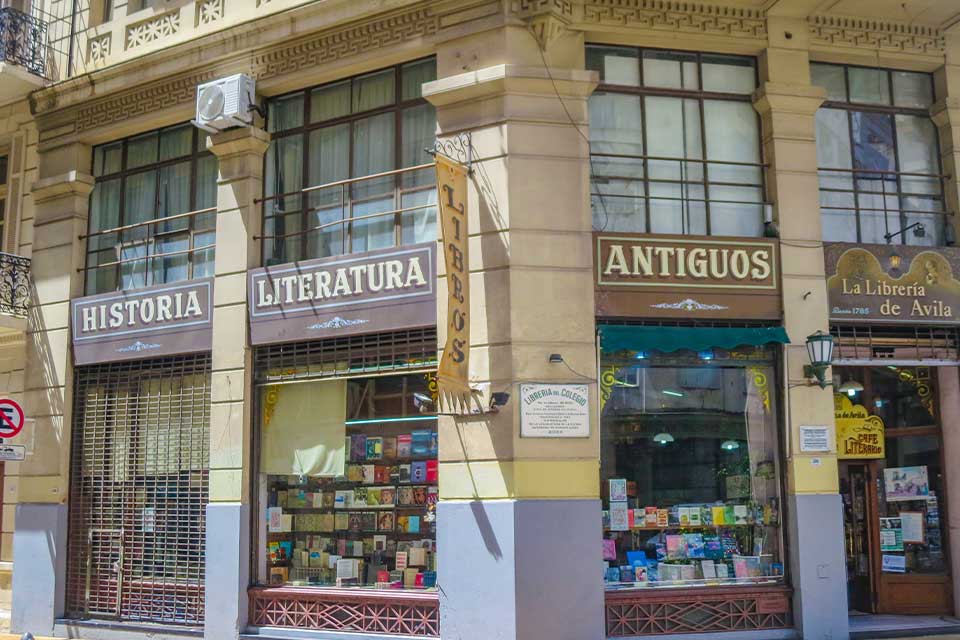

A cinema transformed into a bookstore. The tide of history turned on its head: instead of films adapted from books, the enormous hangar is now home to books promising films that can never do them justice. It’s narrow yet seems to stretch on forever. According to local memory, the cinema specialized in showing films for children. At the back, where the screen used to be, books are piled up haphazardly, forming hillocks and mountains. Fingertips at the mercy of chance as you turn books over like rocks. Walls of shelves of discounted volumes, sent from a distributor to a bookstore, from the bookstore to a middleman, and from the middleman to this second bookstore where they die their final death—or rather, are revived in the hands of their very first reader. The laying on of hands.

The secondhand bookstores of Buenos Aires almost exclusively adopt a decor better suited to barques, caravels, or galleons. Or, when the dimensions don’t allow for such grandeur, just their cabins. E la nave va. Tables and bargain bins become cocktail parties for browsers, vernissage for dandies with Merovingian hairstyles. Back rooms, annexes, cellars. A bookstore basement you’re not allowed into is the Grimms’ fairy tale a reader needs in their “mature years,” a story read out loud (you can’t see the page, or the book). Some secondhand bookstores require both employees and browsers be adept spelunkers and climbers, able to keep a precarious balance while carefully removing books to see what silently awaits in the rows behind. Three rows of books per shelf. “To me, a secondhand bookshop is what a roulette wheel is to a gambler,” said John Betjeman in Mephistophelean mode.

The secondhand bookstores of Buenos Aires almost exclusively adopt a decor better suited to barques, caravels, or galleons.

Bookstores whose purpose is to offer up a good idea—especially when one is pressed right up against the ceiling and enveloped in woody aromas—of how the literature of this or that country has produced and accumulated its goods, mummies, and sacred ghosts. (By the way, one could draw a ghost map—a litany—charting the lost English-language bookstores of Buenos Aires: Mackern’s, Mitchell’s, Galatea, Murphy’s, Pigmalion, Robert Grant & Co, Perkin & Co, Harrod’s.)

The infinite search continues across tables that are never quite given time to recover from the ocular raids of maniacs who wander the city—from one bookstore to another, one stand to the next in plazas and boulevards, according to preestablished plans or erratic whimsy depending on how serious the condition of the searcher is. Believers and adepts who aren’t always aware of what’s in play when they enter a bookstore: inherited interests, retrospective interests, mimicked fetishes, passing fancies, financial status, the gifts one has made to relatives so far this year, the time now and how much you have left. Months and years wasted—lost time—searching bookstores for the slightest hopeful glimmer. Hours spent standing in a bookstore, on a journey through the cosmos, beholden to a notion in which the idea of actually buying something has taken a back seat (the smell of spent fireworks). One might trade one’s life, let’s put it that way, for a book that until just now had seemed necessary or even essential, a conviction that within a matter of milliseconds collapses under rational scrutiny.

Grottos, caves, dives exist in a Buenos Aires that, together with Paris and London, is one of the few metropolises where one can superimpose a bibliographic, literary—but not fictitious—atlas onto the real one. It’s bad luck to name secondhand bookstores in the present; they must be allowed to live untouchable in the past, in their capsule of Brahmanic time. Within their bubble, surviving bookstores act as stations, terminals, bell towers. Bookstores that welcome entire libraries formerly belonging to those who definitively departed weeks or even years before, libraries through which one can reconstruct a life. The enigma of well-honed taste—a taste generally cubist in nature that might unwittingly fill a gap or offer a wholly unexpected revelation.

The bookstores of Buenos Aires harbor memorable profiles and silhouettes. The employee who mimics the owner’s character—curt, dour, listless—as though it were the only way to keep his job. The bookseller who bids farewell to a couple of volumes, advises gently sanding the edges and using soap for the covers: “If you learn how to do it right, the book will be unrecognizable.” The bookseller by the river with a milky eye who hails myopic customers with the greeting, “I have the same glasses as you, but you beat me by an eye.” A bookstore located in a shopping gallery across three noncontiguous units, with one lamp and in its yellowy light the owner, the same man from ten or twelve years ago, who hasn’t aged a day. He asks the visitor to take off their backpack (he’s just accidentally knocked down a volume of Eliseo Reclus), saying, “Only a man on horseback or on a bicycle is aware of precisely how much space they occupy.”

Like its reflections and extensions, such as Montevideo or Rosario, Buenos Aires revels in an extremely varied gallery of readers.

Like its reflections and extensions, such as Montevideo or Rosario, Buenos Aires revels in an extremely varied gallery of readers. A reader fascinated by the density, the rhythm, the serenity she finds in books “of text.” Another who lines all his books in brown paper so no one can see what he’s bought or what he’s reading. An excellent reader of bad novels. A decidedly intermittent reader who indulges in brief, spread-out bursts, deliberately seeking to create an uncanny effect. Supremely snobbish readers who declare that they don’t like Shakespeare but are fascinated by the Elizabethan era. The reader who feels they can do anything with a new pencil. The reader who doodles in the margins while they read: characters from the novel, a passing face that lingers in the mind, a mug, a spoon, another table, or stairs. A reader who seeks the ideal reader inside himself—perhaps that’s why he travels? A reader of signatures and dates on the first page of ancient books. A reader who, during precarious and outlandish periods of their life, reads biographies to economize—finding familiar moments and places (dates, coastal towns) that an admired author has had the good grace to commemorate.

Buenos Aires