The Classroom That Disappeared

When a mysterious teacher and his eighth-grade students disappear, the subject of transformation appears along the investigative trail.

The center’s phone rang. A tense voice shouted: “An entire class’s students along with their art teacher at a city school have disappeared!” At first, we didn’t understand what that tensed voice meant by “the students disappeared.” We went to the school, and the astonished principal interrogated the remaining scared students and us, too. They all agreed; they saw that “weirdo teacher with his tree-patterned shirt, treelike hair, and treelike eyes” and his eighth-grade section C students enter the classroom at the start of the second class. They never saw the door open. They didn’t see any student taking a bathroom break or bringing chalk or papers or anything else.

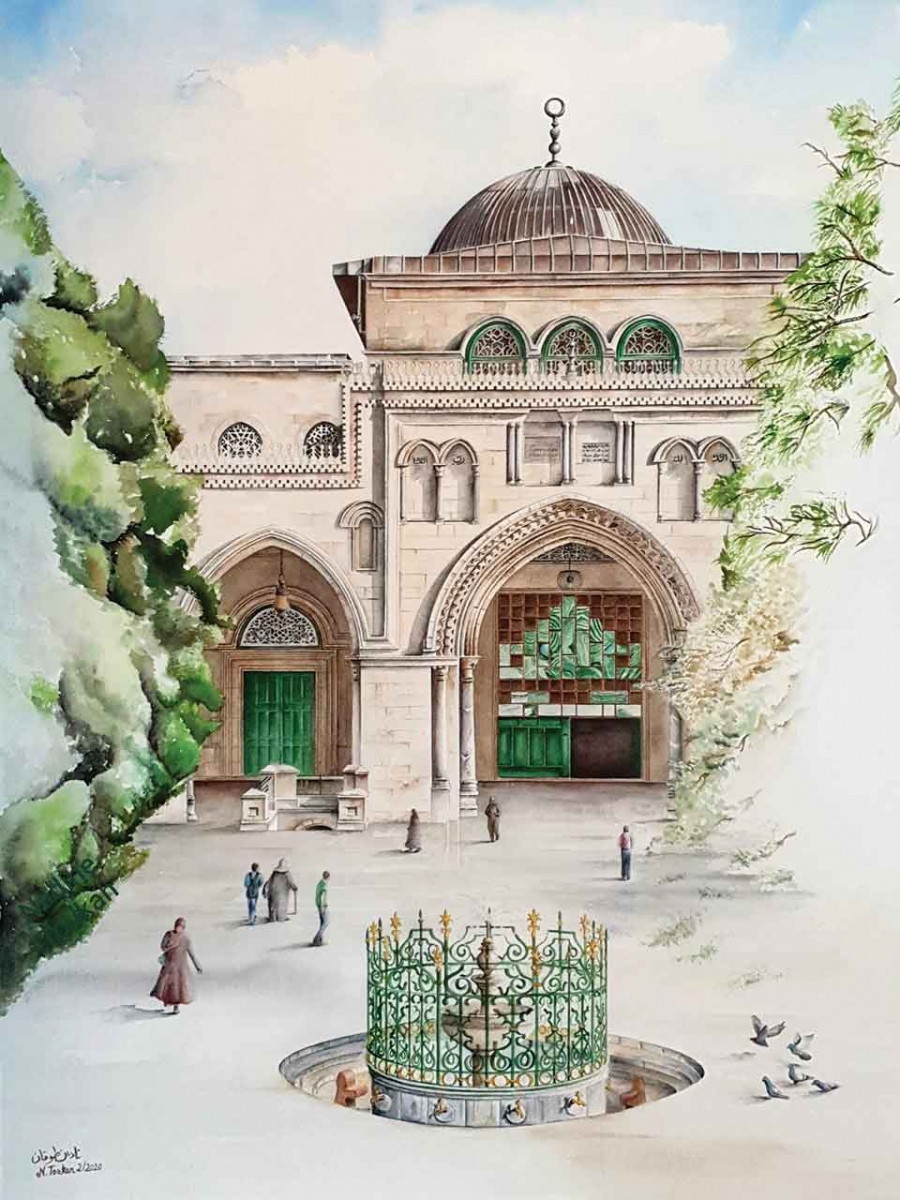

The principal told us that he was never comfortable with that teacher ever since he was appointed two years ago: “He doesn’t converse with teachers, spends most of his breaks in the library, shuts the door on himself, and strange music interspersed with the sounds of birds, animals, and people crying, dancing, and praying can be heard coming out of there. Since his appointment, the relationship between that class’s students and that teacher with his tree-patterned shirt, treelike eyes, and treelike hair was strange. Almost from his first class, the students changed suddenly; they became inclined to silence. When they entered or left the school, they’d walk as if they were preparing to depart on an upcoming flight. They looked at the sky a lot, and they no longer played and ran after one another. They spent their break inside an ancient house with a circular roof, a scattered floor, and thick and messy walls. People in the neighborhood say it’s the tomb or dwelling of Sidi Negm, a saint who died five hundred years ago. Only that strange teacher has the key to that house. He’s an art teacher, after all.”

In his testimony, the school’s caretaker mentioned that he heard two students from the class whispering to each other the following sentences:

The first student to the second: I chose to be a wild bird.

The second to the first: I chose to be a wild horse that does nothing but run, wit a back that no one but the wind can ride.

The first to the second: Lower your voice! If people knew what we intend to do, our plans would fail. We would remain ordinary human beings driven like sheep in the temple of eternal obedience.

The second to the first: Do you know what it means to be a wild horse that does nothing but runs? With a back that no one but the wind can ride? It means I’ll taste the wind as it melts in my nostrils, and I’ll mix with the wind till I am no longer able to identify myself: Am I a horse or wind?

It means that I won’t be scared when the teacher says, “The exam is tomorrow, so be prepared or . . .” It means that I won’t consent to the headmaster’s threats when I cut my hair the way I like it to be or attend with a dress chosen by me, not by the rules. It means I’ll protest when the math teacher smacks a classmate for his constant smiling during class.

The first to the second: Oh my God! What did this crazy teacher do to us? And do you know what it means to become a wild bird? It means I won’t stand in the morning assembly listening to the boring national anthem and yawning with hundreds of other yawns from my colleagues. I won’t be subject to their orders: “Bend up! Rise up!” It means I’ll have a perspective different from the ant’s narrow one.

The second to the first: Oh my God! What did this crazy teacher do to us?

The PE teacher’s testimony:

“While I was on the playground teaching fifth-grade section B students the art of bending before barriers, the disappeared students and their strange teacher passed me in silence. All of them vanished into the darkness at Sidi Negm. They shut the door behind them tight, and an incomprehensible silence followed.”

Testimony of Ayman, a student in fifth grade, section B:

“I swear I saw what looked like the tip of a shiny silver wing implanted in a student’s waist.”

Statement of Um Ahmad, the school’s neighbor:

“From my balcony overlooking the vanished students’ classroom and with my own eyes, I watched the classmates drawing strange shapes in the air with their hands. Their tree-eyed teacher, with the tree-patterned shirt and treelike hair, was also drawing. His eyes protruded, and frightening emotions flowed in his face. Suddenly, I saw them either embracing or wearing their drawing, then they disappeared from before my eyes. At first, I thought my weak eyes were imagining such strange things.”

From my balcony overlooking the vanished students’ classroom and with my own eyes, I watched the classmates drawing strange shapes in the air with their hands.

The investigators were confused.

The head of the Investigations Department at the Madinah Police Station gathered the principal, students, caretaker, PE teacher, the old lady, and teachers and presented them to the investigators. The office space was overwhelmed by a sense of great helplessness. The president felt a great embarrassment in front of the journalists who poured into the center. The cries of the students’ families, their violent commotion at the center’s gates, and their threatening demands to reveal the secret of their children’s disappearance only heightened confusion and chaos.

The Israeli occupation denies arresting students:

An official source of the Israeli occupation forces denied any responsibility in arresting eighth-grade section C students in a school in Ramallah. The source stated that no incidents in the area were reported to justify their detention.

News of the disappearance in a local newspaper:

“An entire classroom, along with their art teacher, disappeared in a school in Ramallah. Police sources stated that the circumstances of their disappearance are very ambiguous. An official source in the ministry of education said there’s no evidence of a criminal or political crime and that the investigation is still ongoing.”

The art inspector’s report on the disappeared art teacher:

“I wasn’t too fond of his appearance. His hair is long and messy. The way he teaches drawing is suspicious; he doesn’t believe in colors. The air is his primary material; his brush is his hand and mind. The teacher didn’t utter a word; his finger and eye gestures are his methods of teaching. I recommend that you pay attention to him and follow his behavior. He might pose a danger to the students’ minds.”

The principal’s report on the art teacher:

“I don’t know precisely the nature of that teacher. Sometimes I feel that he’s straightforward, and sometimes I feel afraid of his thoughts and behavior. He doesn’t mingle with other teachers nor shake their hands. He suggested that I cancel the national anthem from the morning assembly because continuing to hear it causes students to get bored, frustrated, and nihilistic. He suggested replacing it with songs by Fayrouz or Abdel-Wahhab.

Once he suggested canceling the uniform and letting students choose their own clothes, each according to their taste, thoughts, and dreams. I recommend sending a committee to examine this teacher’s psyche, as he might be a danger to coming generations.”

A sad night’s revelation by a mother of a missing student:

“Lately, he used to look at the stars a lot. His physical energy had recently weakened, while his inner mental strength had escalated, dangerously so. He locked himself into his room. I observed him from the peephole drawing strange shapes in the void. One time he drew what looked like a horse, another time a sun, then three high houses like mountains, remote islands, birds of different shapes and colors, and strange trees with massive trunks. He always told me that the freedom of his hand, while he was drawing or digging in the air, leads him to a delightful feeling. To paint while focusing and denying the material presence inevitably leads to the drawn figure’s embodiment and true existence. He told me that the tree-eyed art teacher once told him that while he was drawing a horse in the nighttime void over a high, barren Jericho hillside, in a time when the world was silent and sleeping, a horse suddenly crouched in his hands. Hence, he rode it back to Ramallah.”

What did the spirit of Sidi Negm say?

“They used to come to me lightly, drunk with silence. Their teacher is a crazy being who instigates transformation and dissolves in things as a way of learning, love, and life. He tells them in a dreamlike voice: transformations are the secret of this universe; people in their ordinary preoccupations are oblivious to their surroundings, like rocks, trees, rain, and clouds. So if we stare at a tree’s huge trunk, we would’ve heard breathing, crying, or a call, prayer, or dancing. The problem with people in our world is that they don’t know the meaning of the word ‘gazing.’ If they knew its taste, their lives would have changed; they would’ve discovered how broad, beautiful, and powerful they are. Gazing allows you to regain the meaning of your invisible powers. Gazing purifies the air that you breathe and portrays the tree for you as your mother and the cloud as your grandmother or neighbor.

Their teacher is a crazy being who instigates transformation and dissolves in things as a way of learning, love, and life.

The students carried their teacher’s words with a quiet joyfulness. I used to see them gazing at my rough, cracked walls or a green herb persistently peeking out of the cracks of my hard circular roof. They’d spend the duration of the class gazing without any movement. They were not bothered by the sound of students playing outside; that tree-eyed teacher trained them to fight the outside, freeze it, or arrest it in the grip of their concentrated separation. I loved that teacher, and those students charmed me. It was the first time that such a group of people visited me. They respected my space’s prestige, and they knew my values and history. I’ve been accustomed to the superficial and noisy: messing with my guts, rudely plucking my grass, scraping my walls with their stupid legs, stealing stones from my yard, and cursing my roof’s history with their acrobatic jumps.”

The disappeareds’ short messages:

In a press conference, the city’s police station finally reported that the investigators had found paper scraps with short messages written by the eighth-grade section C students jammed inside Sidi Negm’s walls. They also found drawings of the objects and tools they’d used to vanish.

The teacher: “I am not in hiding. I’m amongst you. Don’t you see me?”

Ahmed: “I Am a fish in a nearby sea. I will never return to your land. From the water, I learn to expand.”

Radi: “God, how beautiful the wind is billowing my horse’s neighing. From the wind, I learn the art of arousing my lost roots.”

Saleh: “You idiots! You eat my fruits and claim my disappearance?! From fruits, I learn how to draw out life from my death.”

Khalil: “My death is indeed near, but I keep the flame’s secret and the flower’s sweetness, learning tolerance and the nobility of departure from butterflies.”

Shaker: “Come to my waves; for I Am a friend of rocks, ducks, birds, children, and boats. From the sea, I learn the true history of things.”

Muhammad: “I Am the messengers’ refuge, and you are a refuge for boredom and emptiness. From the caves, I learn how to hide the ones fleeing tyrants.”

Yasar: “My flesh is white, my soul is blue, and you are hungry coals. From whiteness, I learn the pleasure of emptiness when it refuses to sell itself.”

Malek: “I Am the idea; you are the hesitation. From the mind, I learn to link a kingdom’s fall to its king’s sexual impotence.”

Osama: “My steps are wide, O ye servants of geography! From flying, I learn the energy of expansion and depth of vision.”

Hashem: “With no past nor future, I breathe eternity. I Am time. From eternity I learn energy’s expansion.”

Yusuf: “A cloud I Am, hanging over your necks. I watch your desert and smile. From clouds, I learn pride.”

Translation from the Arabic