A man in a white shirt on his way to somewhere stopped, looked, and saw . . .

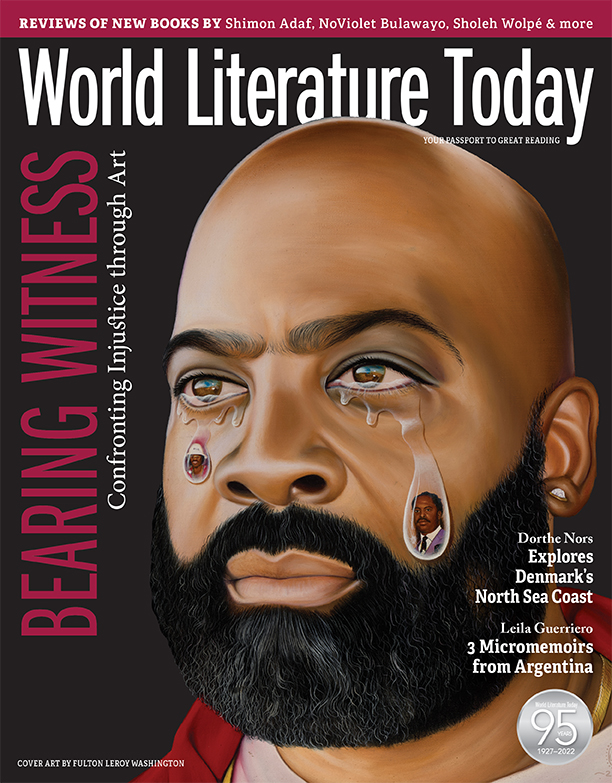

“There are presumptions, in the world as it is now framed, of who the worthy victim is and who merits the power of full witness,” writes Caine Prize winner Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor. In the following essay, she reflects on how witness frames what it means to be human.

BUT FIRST:

On June 18, 2022, at 14:06 hours, the Kenya Wildlife Services posted a notice to the world on Twitter:

A King has rested.

The message continued: “Sirikoi, one the most iconic lions of @KWSNairobiPark was born in January 2014 in the Sosian Valley. He came from the MF family one of the dominant and charismatic pride. He was a majestic lion with tactical [and] amazing hunting skills that enabled him take down big preys like giraffes and buffaloes [on his own].”

The syntax and worldview has the signature of East Africa, where throughout history, the great ones do not die, they rest. That this witness and eulogy is offered to an iconic lion, a nonhuman, does not take away from this call by custodians, to the world, to make note of this passage.

There is a beckoning embedded in this seemingly mundane notice that for perhaps a billion others reads like an exercise in wastage. Yet it points to a fundamental issue that sometimes gets overlooked: that of the meaning of the power of being, or the life that infuses us all under this mysterious cosmos, of the point that life, however it is lived, matters. But there is also a gesture to a particular vulnerability: the need to be attended to. Sirikoi’s feats are noted because his presence was attended to in a city that had made such “witness” possible.

Another animal fable, adapted from Chinua Achebe’s Anthills of the Savannah (1988) and elaborated on in a long-ago conversation with the outstanding Kenya British visual artist Michael Armitage as we contemplated the idea of the artist as witness. Amplifying this idea, he remembered Achebe’s fable.

Here is a simplified version from Anthills:

The Leopard who had a craving for a tortoise-flesh gourmet meal sought Tortoise avidly all over the land. Tortoise became aware of Leopard’s lust for his flesh and proceeded to manage his presence, treading the earth with extra caution, staying close to shadows as he traversed roads that were far from Leopard’s usual roaming range. But as fate would have it, one dawn, Leopard, who was in a bad mood, was crisscrossing the savannah and turned down a lonely road. Lo and behold, there was Tortoise ambling along, whistling and ready to experience the brand-new day.

“You! At last!” Leopard exclaimed. “I have caught you! Resign to your fate. Prepare to die.”

Tortoise sighed.

He had had a good run. Submitting to the inevitable, he said, “Fine. But allow me a final request?”

Leopard, feeling magnanimous in this moment of triumph, agreed.

Tortoise began to churn the soil with force. He scraped wide lines into the soil, creating holes, tearing and dumping vegetation over quite a significant radius.

Leopard became alarmed. “What are you doing? Why?” he cried out.

Tortoise replied: “When I am dead and gone, all who pass by will bear witness to this place. They will read the disordered ground and conclude: “Two great beings struggled. It was a long and good fight. It was right here that a fierce and brave soul met his match.”

***

EAVESDROPPING ON A fascinating conversation in a coffee shop in Nairobi. I do not know who the individuals are, but one keeps going back to the notion of the “sovereign person.” It feels like a fresh amalgamation of ideas; it probably isn’t. Sovereign has linkages with authority and power, of independence and a certain supremacy over a situation. It perhaps implies a certain supra-ability to choose and act. I want to lean over and ask that person, But given the character of the world today, and a document conjured in the USA I have just read in disgust (the H.R. 7311 – Countering Malign Russian Activities in Africa Act) in its blithe subsuming of and cannibalizing of even the idea of African self-will, a document that is quite emblematic of the state of the world today and its denials, refusals, delusions, and presumptions, I want to ask the “sovereign personhood” advocate, What gives him the confidence that one can still mull over individual sovereignty today?

My Kenya coffee latte is cooling, and I am suddenly reminded of another human who I did hold in awe, who went against the grain, no matter how the world looked at him for doing so, the lamentedly late lawyer Jacques Vergès, born when Thailand was still Siam, of Vietnamese and French heritage, brought up on Reunion Island and of Algerian and French citizenship, who defended Algerian National Liberation Front revolutionaries during the Algerian war for independence. He suffered for that and his other choices, which included spirited defenses of high-profile individuals accused of heinous crimes against humanity and society, including “Carlos the Jackal” and Khieu Samphan, former head of state of the Khmer Rouge. “I’d even defend Bush (George W.),” he is reputed to have stated, “but only if he agrees to plead guilty.”

Evil will not have the last word about what it means to be human.

Jacques Vergès had this capacity of laying open the respectable veneers and the mainstreamed virtue-signaling that has characterized so much of our age, the projection of the most vicious crimes against existence on select individuals while ensuring that the sepulchers of our actual lives remain whitewashed by consensus. His was one of the most defiant and furious witnesses against the cult of human hypocrisy that has shoved the world to this terrible crisis point, and yet, in all this, in an interview he gave before his death, he observed almost as a side-thought that he chose this path to prove to himself that even in the anguished void of human failings, in the dark holes of choices that elementally offend, evil will not have the last word about what it means to be human.

Vergès refused to succumb to the cult of human scapegoating, the projection of every human transgression on a single person without ever bothering to look within and play witness to our own shadows. He cut through the official euphemisms, the doublespeak, thinkspeak, newsspeak lexica. It is this visceral and almost solitary adherence to conscience and truth (capital “T”) that seduces me the most, to which I desire to adhere as Homo testor. It is so rare to find such a human in this world, as the woeful and nauseating example from the cognitive warfare linked to securing a common thinking around the recent European war reveals. The war on conscience, will, and the evidence of the senses is a war on witness and testimony of being. Thankfully, there are vestiges of resistance in spots of the world.

The war on conscience, will, and the evidence of the senses is a war on witness and testimony of being.

Back to Vergès, what his life means for some of us is that whatever else is presented to me the human being, in this time and place, one of my sovereign choices in this wrestling ground of being is to endeavor to consistently shine a light deep into the abyss, using an arsenal of words that cut to the marrow, to affirm the highest ideals embedded in the human spirit, to deny power to that which violently intends to consume, deny, desecrate, divide, and mock our existence. It requires not so much an act of will as much as an act of unrequited love for humanity and life, even in its failings, faults, suffering, offenses, and woundedness.

I turn around again, this time hoping to see the face of the “sovereign personhood” defender and to catch his eyes. But their table is empty, the remains of drinks shared in three empty glasses. A petite waitress approaches to clear them.

I tell her, “Two human beings struggled there.”

“They did?” she asks, her eyes wide.

“Yes, secretly, with eavesdropping ghosts and their friends.” She stares at me.

I laugh. She laughs.

“Who won?”

“I’m not sure yet.”

***

ON JUNE 24, 2022, several humans from different parts of the African continent, having made their ways to Morocco, strived to jump a fence to reach the site of their illusions, Spain. It culminated in a massacre noted for the promulgation of stories—when they appear—that reduce the number of casualties, despite the visual evidence of the harrowing of hundreds of mostly young men. The news, and the horror, is treated in the mainstream channels as not-news, barely mentioned, and there are no flag-supported hashtags or voices raised in outrage tearing their metaphorical hairs at the sight of this human aberration, this offense to decency and meaning. It is the in-between spaces that are the sites of revelation; the silent witnesses for whom the vision and the neglect of the consensus will inform choices, now and in the future.

The sundering of the world into “The Rest” and “The West” is well underway. The attempts of the West to unite the world around the scapegoating of their designated enemy while elevating their chosen victim fell flat and has elicited an excess of strange emotion and overreaction (the H.R. 7311 – Countering Malign Russian Activities in Africa Act) by the West and a hardening of a posture of indifference by most of “The Rest.” Reading the entrails and the reality of multilateral agency helplessness, the rupture will only widen, is widening, as evidenced by general “global” indifference to the Melilla Massacre.

There are presumptions, in the world as it is now framed, of who the worthy victim is and who merits the power of full witness. The fin-de-siècle zeitgeist, the historical shifts that are unfolding, the coalition of well-dressed warmongers (“arsenal of democracy”) who have decided that theirs is an existential battle of Armageddonian proportions—the overt envy at the ascendance of China at the expense of a five-hundred-year-old hegemonic condition. Raging against a season of human transformation—multidecade wars for which no accounting has been rendered, the restoration and ascendance of previously dominated civilizations, pandemic patterns, climate travails, wars and rumors of war, energy, food, and meaning crises—suggests, although it shouldn’t, that humanity is likely to slither into yet another self-inflicted conflagration, to put out yet another summons, mostly to boys and men to offer their lives as a sacrifice in the service of war gods.

A liturgy of lofty words and soaring rhetoric conceal the reality: a resorting to atavistic tribalism, a primordial beastliness (“ethnonationalism”) that finds full flourish and ecstasy in the ritual wasting of human blood, in all the hideous groans that are the soundtrack to extreme human suffering. Within ourselves, we know this; we are, after all, history’s witnesses, except that we will bury our knowing within mythologies and an overintellectualization of our shadows so that we can foolishly justify the inevitability of a Götterdämmerung. What was supposed to be the great window to objective witness is so hopelessly intertwined with the chaos and has, at best, become a mere mouthpiece for sociopolitical positions. Hubris guarantees that humanity has learned how to ignore the canaries down the mine shaft. The public and humiliating flight from Afghanistan after twenty years of violence and horror, in a war against the underarmed, who because of their refusal to succumb to willful terror are being punished by those they defeated, who are facing universal poverty as is the once-thriving Libya with its now emblematic open-slave markets, while the perpetrators manufacture new forms of outrage for bespoke wars and, in more hysterical tones, affirm their supremacy as once did the Wizard of Oz.

Mine canaries are the disastrous consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic, the very public collapse of much-vaunted health systems that led to extreme mortalities in the parts of the world that had wished those high mortalities on “The Rest.” It is those piled-up bodies of newly broken men, joining the forgotten heaps of previous ones, that evoke sites of previous human genocides, the most resonant being those from the last Euro-American firestorm known as World War II. Atavism blinds; a pathology framed as “whiteness” and “blackness” (and the proximities) or those who share “our interests, security, and values” ensure that the necessary and thoughtful conversations about implications of a human situation get sidelined. The necessity of collective witness that would reveal a truth that might set free is abandoned, and we collectively collude in our own destruction. Anyway, nations have allotted most of their budgets to its realization.

***

WITNESS STATEMENT:

“Quos Deus vult perdere, prius dementat.”

(Those whom the god wishes to destroy they first turn mad.)

***

A MAN IN A white shirt on his way to somewhere stopped to look and see, to really see, and all his body held in stillness the disgust of a conscientious world.

On January 19, 2010, a beautiful fifteen-year old child, Fabienne Cherisma, was killed by a stray bullet while looking to salvage something from out of the horror that was her earthquake-hit city, Port-au-Prince, Haiti. She fell into the picture frames she had retrieved.

Her father’s name is Osam, her mother, Armante. “She was very intelligent,” Osam said. “Her head was full of knowledge.” (The Guardian, January 26, 2010)

There is a beautiful child in pink and white lying dead. She clutches picture frames, with her legs outstretched. She looks asleep on the white ground. But in her dying, she is being subjected to the most awful and rapacious gaze of gluttonous men, angling their twisted bodies for a “money-shot,” desecrating, defiling, and adding to her wound and that of humanity.

We saw it, too, what witness looks like when it is degraded.

We saw it, too, what witness looks like when it is degraded. When it becomes a grotesque signal, a revelation of a people’s intrinsic moral disorder that gestures to indescribable ugliness.

A different kind of witness, photographer Nathan Weber captured the moment and evidence of egregious awfulness. Later, one from that wake of vulture-photographers, Paul Hansen, was awarded a “Swedish Picture of the Year” award, a case study in our still-unacknowledged clash of ethics, values, and morality, that which we differently live from our unique responses to the question: What does it mean for me/you to be human? What does the humanity of the other mean for you/me? The witness of Weber’s photograph illustrates the shadow gulfs between our worlds, site of secret objections and conflicts.

What does it mean to be human? Not this.

In my lore, lexica, and world, necrophilia and the disregarding of the rights of the dead are like necromancy, an existential abomination. For the Swedes and most of the Occidental tribes, these habits are listed in the category of “art.” Still, a light in this labyrinth of Minotaurs, a gesture to the space of sacred humanity: the acquisition and use of the images of Fabienne’s death stirred global discomfort and elicited a debate on ethics. There were overexplanations and justifications that in an oblique way do affirm an awareness of a shared sense of right and wrong, even if the wrong was defiantly propped up and reinscribed as an “act of witness.”

What does it mean to be human?

Not this. Never this, never like this. Not this will to close up on the face of a dying/dead human without choosing to accord dignity, to cover the nakedness, to protect, to grieve, to cry out as a human should; to shield the vulnerable, even the vulnerable dead.

But.

See that tall man standing in a white shirt, who gapes with clenched fists at the coalition of scroungers in that tableau of horror?

Horror cannot have the last word.

His disgust says it all.

Still, light.

Nairobi