Strange Scrawls

Reading a secondhand copy of Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine, a reader encounters another consciousness in the margins.

I’d like to say that I stumbled upon this book on a rainy night as it lay alone in the gutter, but the truth is that a regrettable ex pawned off this paperback like another pretentious thing to eventually jettison. While the front cover still bears the author’s name, it has yellowed from sleek pearl to dusty bone, stippled with innumerable stains that could very well be rheum or nasal mucous from a dozen previous readers. If you’ve ever perused a secondhand bookstore, this fits the description of a typical binding on the shelves.

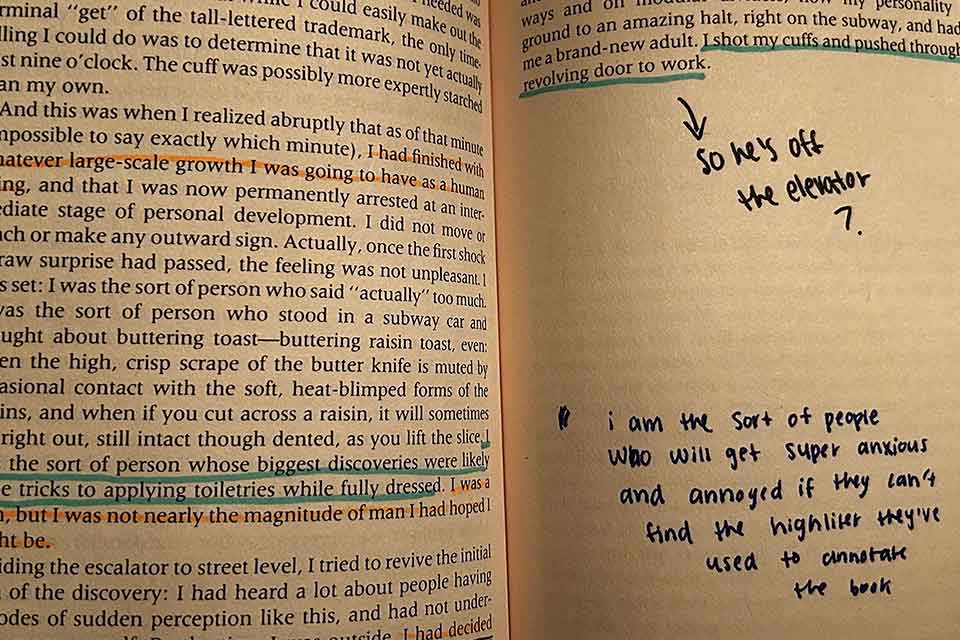

But what distinguishes this old copy of The Mezzanine is the annotations left by a former owner who signed their government name in the cyan of a Crayola marker—like graffiti scribbled on boulders and the ruts of wagon wheels that commemorate those pilgrims who came before to navigate this narrative route. And when I finally embarked on my journey through this slim piece of literature, I found myself veering off course into an unexpected detour that is only to be found in this copy of Nicholson Baker’s 1988 debut novel. While proceeding over the footsteps of an English student whose name came to represent a disembodied intellect, I began to address my companion in the margins by the more succinct acronym of AG out of respect for their anonymity—I know that I wouldn’t want anyone name-dropping me if my annotated texts from high school hit the shelves of a book depository.

Although I pulled it off the shelf to take a ride with Nicholson Baker, I soon discovered that AG’s literal color commentary actually helped propel my momentum through The Mezzanine as I found myself scouring the margins for the smallest crumbs of insight into AG’s mind. If Baker’s footnotes in The Mezzanine serve as an apparatus to introduce new anecdotes from the narrator about objects, AG’s marginalia are a second apparatus comprised of strange scrawls and cursory remarks that inject another consciousness into the fold of this particular binding. Thus, I wasn’t only interfacing with one author but another reader whom I knew nothing about, from a long line of readers whose hands eventually placed this copy in my library. To better understand my place in this chain of secondhand ownership, and to document my newfound obsession of slowly constructing a mental picture of AG as a reader, I soon classified AG’s annotations into three categories.

(1) Reactions: “so weird,” “awkward!,” “childish” are the most common, reappearing every ten or so pages. And when the narrator laments on the shuttering of a business such as home milk delivery, AG scribbled the drollery of a frowny face. Besides this flourish, AG did not leave any other pictograms that clue us into any emotionally potent passages that might have kept AG at least mildly engaged in a text that mostly provoked, from what I can surmise, a bemused attitude toward the quirks of the narrator. The predominant characterization of AG’s annotations are the majuscule abbreviations of texting like “LMAO WTF,” “WTF is he on,” “did NOT understand anything,” “his connections to PPL are so shallow,” “but who TF remembers this in detail?,” “FINALLY stops talking about towels . . . NVM.” And whenever the word mezzanine appears in the text, AG has helpfully circled it for us like this book is also a word search. But after adjusting to AG’s typical remarks, I found it conspicuous how they didn’t mark certain passages with “so weird,” as if they fell asleep behind the Crayola when the narrator recounts how he stole the paper from his parents’ shoebox to “poke a hole in one of them, using a pencil or toothbrush, push [his] crayon sized penis through the hole and urinate into the toilet.” When given the choice to select passages for the class to read aloud and examine, students tend to avoid those unseemly paragraphs with racial expletives or sexual details, even if they may be pertinent to an argument like AG’s observations about an emotionally infantile office worker in The Mezzanine.

(2) Questions: at the end of the first chapter, AG posed a question that rivals even the most vivid images that Baker limned for me; AG seated in class while dictating their professor’s instructions for an undergraduate essay on whether “Baker achieved a literary work of profound complexity or is The Mezzanine a trivial novel completely lacking plot.” From the evidence, it seems AG’s reading of The Mezzanine falls into the latter. And while reading this copy, I intermittently wanted to scream at AG as a way to declare that I refused to allow their captious comments to tint an iota of my textual relationship with the principal author. I couldn’t just sit around and read. I finally had to click my ballpoint pen and bring the fight to AG’s domain of the margins, countering their jabs with the fact that the narrator’s acute awareness of social minutiae and their obsession with the evolution of mass-produced objects is not only comedic but also poignant, as it demonstrates the isolation of the average white-collar Joe who can only sustain a meaningful relationship with another person through mundane sundries like the milk carton or stapler and communal spaces like the bathroom or the mezzanine.

I couldn’t just sit around and read. I finally had to click my ballpoint pen and bring the fight to AG’s domain of the margins, countering their jabs.

(3) Interpretive dead ends: I think everyone, at least once, has formed a prediction about the trajectory of a story that later proved to be wrong by the dénouement. It’s natural for everyone to form their own deductive hypothesis about where things are going, but as any teacher will say, there are readings founded on evidence and readings based on baseless assumptions. And when AG writes “does he have a good relationship with his dad + where is his mom,” and “finally mentions mother,” and “has mom + sis yet mentions dad more,” they seem to be probing an area the story isn’t pointing toward but, instead, where they want the novel to go. If I’d never crossed paths with AG, these questions would have never entered my mind because the dynamics of gender and narrator’s family aren’t even a passing concern for the novel. It’s like AG wants to put down the pavement to a road that isn’t even on the map. There are certainly benefits to teaching students how to write an essay about a novel in clearly defined parameters, such as a Freudian reading, a feminist reading, or a Marxist reading, but if a student is to take their training outside the confines of a carefully curated syllabus where their knowledge from the classroom neatly pertains to the texts on their literary diet, they could be looking for the shadows of an interpretation that takes no solid form in the work of an author who does not play into the critical compartments of their education.

I like to think AG always intended for someone, a friend or a stranger like me, to enjoy their marginalia with meta sort of admissions that they are “the sort of people who will get super anxious and annoyed if they can’t find the highlighter they’ve used to annotate the book,” which AG wrote in a black pen that deviates from the previous annotations, all written in blue ink. In high school, I also annotated all my books. But after graduating, I got reacquainted with those strange scrawls and inscrutable logical leaps on subsequent rereads of my paperbacks from eleventh grade; my attention invariably strayed from the story that I initially flipped the cover to read in the first place to the cringy, illegible remnants of my younger intellect.

I take issue with annotations now because they only offer a glimpse into the mind of a reader during one pass through the story.

I take issue with annotations now because they only offer a glimpse into the mind of a reader during one pass through the story. What if you’re to reread a novel twice or ten times? Can you legibly write over your old annotations? This is the problem: the physical book falls from the realm of the ideal where it can be read countless times—with each experience being different from the last as the reader’s relationship to the text evolves—to the reality of how a physical copy is permanently marred by the nearsighted marginalia left by the reader’s first pass through the story. However, there’s also a solution. If annotations help you get more out of a book, they only help you work through one reading of the text, leaving a mess that you or another reader in the future will have to wade through.

After confronting those blockheaded guesses left in the margins of various novels by my less developed frontal lobe—which is like looking at a photo that isn’t quite old enough for any sense of nostalgia to compensate for how it may not have been an especially photogenic moment from the past—I switched to the apparent solution: sticky notes. As many people already know, they provide the utility of directly annotating without permanently tainting the page, which leaves the book clean for the reread and allows for more space to jot down some ideas I might later crumple and toss into the trash.

The next time I pull off the shelf one of those novels with the margins stuffed with my juvenile insights from high school, I might gift myself a fresh replacement before I drop the old copy in the gutter, for real this time, to let the next link in a secondhand chain discover a window into the erstwhile Connor like I did with AG.

San Jose, California