The Little Despairs of Despedidas

A Filipino writer now living in Boston explores a tradition of farewell parties that share felicitations to send off people facing the uncertainties of a foreign land—a fête before a leap of faith.

“How was your despedida?” I asked Regie about his farewell party in Manila, between his bites of chicken wings and sips of red wine from a coffee mug. He and Chuck, a friend from Los Angeles, were crashing at my apartment in Boston, before we made our way to New York to meet three others from our high school barkada, or friend group, of twelve. It was a reunion of sorts.

“Nothing is for sure yet,” Regie reasoned, referring to his longer-term plans. After he left Manila in April of last year, he traveled to see our friends in Vancouver and LA, and his sister in Wisconsin, scheduling job interviews along the way.

I pressed for an answer. Though he felt tentative calling it a despedida, he admitted having gone to a bar with two friends on the eve of his flight.

A despedida is an ironic ritual. I was seven the first time I encountered the word as my uncle and his family were preparing to migrate to Australia in the early nineties.

“A party to say goodbye,” my mother replied curtly in Tagalog when I asked what it meant. I was confused by the festivities surrounding a life-defining departure—what was there to celebrate?

I was confused by the festivities surrounding a life-defining departure—what was there to celebrate?

My family went to see them off at my grandparents’ place north of Manila, the street in front of their house lined with parked cars. Inside, guests filed up and down the hallway between the dining area, where they balanced platefuls of food, and back to the living room where the spillover crowd had gathered. It was still months until Christmas, yet the spread on the table had the air of an early nochebuena, the big meal on Christmas Eve. When my family visited my grandparents that Christmas after they’d left, the house felt too quiet and roomy. Also missing was my aunt’s delicious fruitcake, until then a staple on our nochebuena table.

Growing up in the Philippines, I became accustomed to attending despedidas as a familiar social function. My family trooped to the US military base to see my godmother and her husband who served in the US Navy, when the looming shutdown of the base meant he would be deployed with his family to San Diego. Years later, it was to send off an aunt’s family migrating to Ontario, joining her two brothers whose families had settled there in the seventies. But for a cousin who was leaving to work overseas as a physical therapist, a celebration was out of reach. Instead, her family heard Mass dedicated to her safe passage to Saudi Arabia.

Is a despedida warranted only for those leaving for a foreign land, or even for a place that simply feels foreign? My maternal grandparents were subsistence farmers, too poor to hold a proper despedida for my mother as she left their hometown to study in Manila. Instead, they simply sent her off from the bus terminal with bags of nuts, crabs, and fresh produce, as she embarked on a twelve-hour bus ride without air-conditioning. One despedida was too early to recall. Even before my first birthday, my father left for Australia, then overstayed his visa. I was seven when I saw him again.

Were departures necessary before our colonizers came?

As a child, I wrongly assumed despedida to be a homegrown Tagalog word, just as I did barkada. I wasn’t aware of its Spanish origins, meaning “farewell” or “farewell party.” It isn’t the negation of pedir—“to ask”—as the prefix des- misled me. Neither is it a cognate of “despair.” I wonder if my ancestors had a Tagalog equivalent for it. Were departures necessary before our colonizers came? Was Enrique of Malacca, the Malay enslaved by Ferdinand Magellan, afforded a despedida before being forced to board a ship headed to Portugal?

The most heartrending farewell must be the Irish Goodbye. Long before the phrase became synonymous with sneaking out of a party, it meant something more devastating. In Ireland, during the potato famine of the mid-nineteenth century, it was a sendoff tacitly acknowledging that a person who “crossed the pond” would never again hear from their loved ones back at home. And in popular culture, I immediately think of Bilbo Baggins, who threw a lavish party and gave an impassioned speech before disappearing from his own despedida.

In popular culture, I immediately think of Bilbo Baggins.

The first despedida our barkada attended was for Kiko. It was the summer break after our second year of high school. His family invited us to spend the weekend at a hot-spring resort south of Manila. I don’t recall joining them, but I was at the final gathering at his house, mere days before his family’s flight to Vancouver.

One Saturday four years later, our barkada gathered to visit another friend whose family was migrating to the US. Two years later, it was Chuck’s family’s turn.

In 2007, in the weeks leading to my departure to attend graduate school in Germany, I sent out invitations to my own despedida. Actually, it comprised a series of smaller celebrations. Of course there was one for close relatives; another with colleagues who ordered the perfunctory skewered pork barbeque and bilaos of pansit for special office occasions; a lunch with work friends at a local restaurant; and a post-workday snack with my team at a coffee shop. Two weeks before leaving, en route to a dim sum place to meet a former colleague, I got mugged and surrendered my wallet. She picked up the tab instead of me treating her, as is customary in my country. As my date of departure drew closer, the weekly dinners with my barkada soon turned to nightly ones, little farewells stretched out over time, as though an attempt to dilute the sadness of separation. Meanwhile, in the years I’ve been away, my barkada’s despedidas continued: for Regie to work in Hong Kong and later Kuala Lumpur, and for four others who have left for good to Saskatoon, Vancouver, Rotorua via Jeddah, and Copenhagen.

* * *

The six of us only had three full days in New York City, a short yet rare opportunity to catch up beyond the confines of a group chat or Zoom call. On our first night, we stood in the middle of Times Square debating where to eat, though we were mostly preoccupied taking group photos, awestruck by the flashing billboards and marquees, just as much by finding ourselves gathered in one place, halfway around the globe from southern Manila, where we first met in high school twenty-five years ago.

Our reunion was all the more special for Regie and another friend, Gene, who were visiting New York City for the first time. Gene arrived in the US the year before. Once over dinner, I also asked how he spent his despedida. Like Regie, he answered with a variation of “none,” though he confessed having had lunch with family at a seaside restaurant. Not many were aware of his departure. He wanted to avoid jinxing his plans and the ripples of embarrassment if he were unable to leave due to Covid restrictions.

Is a despedida warranted only for those leaving their country with a sense of permanence and finality?

Regie and Gene eschewed a proper sendoff, acceding to their situation’s uncertainty. They each left under the guise of an extended vacation, taking their chances and stretching their patience and finances, willing to undergo the calisthenics of visa applications in pursuit of a longer stay. I know this all too well, having returned to the US in 2016 without a job. Eventually I found work at my old job at an international organization, where for years I strung together short-term contracts. Because of the blurred line between staying and going, we only allowed ourselves a muted acknowledgment of our departure.

* * *

We jam-packed our New York itinerary given our brief stay. We scanned the vastness of the city from the Edge observation deck, circled the Statue of Liberty, and dined at Olive Garden after watching a Broadway show. We lumbered through the August heat, and by the third day, exhausted from our excursion to Liberty Island, I opted to head back to the hotel and stayed in for the rest of the day.

Four friends still lived in the Philippines on my last visit in 2019. One week into my stay, we got together for dinner at a hibachi restaurant, a despedida for another friend’s family who were moving to Canada.

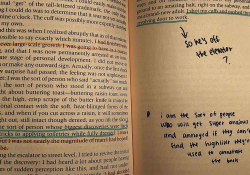

The merriment makes sense now, but only as self-indulgence. Maybe we’re simply finding an excuse to gather and eat well to dissociate from a despondent occasion. The pansit and lechon in our bellies provide comfort from the looming loss for those left behind. I came to accept that the circumstances behind a despedida—the parents’ salary that couldn’t make ends meet; a country that exports its people as seamen, domestic workers, and healthcare professionals; or a life one could only live fully elsewhere—or understandably its absence, comes from a certain kind of despair. We share felicitations to honor people facing the uncertainties of a foreign land, a fête before a leap of faith.

Regie stayed one more week in New York, toured Washington, DC, then came back to Wisconsin in time for Labor Day weekend with his sister’s family. At the party, he shared food photos in our group chat in real time. First was an assortment of grilled meats and condiments arranged neatly on a picnic table, then a canned cocktail served cold, as evident from the condensation. Two hours later came a photo of their dessert, a mocha-colored cake sprinkled with chocolate shavings. On top, made from icing, a greeting in bright turquoise cursive: “Have a safe trip Regie!” I learned he’d found a new job. Five days later, Regie flew back to Manila.

One evening the week I returned to Boston, I found myself quickly swiping through the hundreds of photos we shared in a OneDrive folder. I slowed down upon seeing a series of pictures without me: on a bench in Central Park, over the Brooklyn Bridge, at a seafood restaurant in Dumbo, and at a bar after several rounds of drinks. I skipped joining because I was dog-tired from the long days, or to avoid what appeared to be several rounds of little farewells again, just as I had arranged fifteen years ago. Looking at our photos, I thought about our despedidas back home in the Philippines. I realized the departures relented only because I myself had already left.

Boston