What Are You Doing Here?

In this creative nonfiction from London, a question once asked suspiciously becomes a question a man asks himself as a way of checking in.

The first memory I have of this question is when, as a child, my family had run out of food. Even now, I don’t know the circumstances surrounding this. I’ve never asked my parents, partly because it would embarrass them. They might deny it ever happened. Dad was self-employed, so maybe he was between jobs and not allowed to sign on the dole. Whatever the reason, one night he took me and my brother to a potato field out in the country, near where he grew up. He said my uncle owned the field and wouldn’t mind us helping ourselves to a few potatoes. I knew we weren’t supposed to be there, but, since I was only five and had relatives I’d never met, I believed him.

I had a great time, running through the field, grabbing at the roots of the short green plants, which looked like the dock leaves I rubbed my nettle-stung knees with every summer. We threw away the small pebble-sized potatoes and put the big solid ones, almost too large for my childish hands, into the sack Dad had brought. Dad kept telling me to be quiet when I’d get overexcited, but it was exciting, running up and down the field, the only light coming from the full moon overhead, which lit up the field. The moon seemed brighter than it did in town where we lived.

It was exciting, running up and down the field, the only light coming from the full moon overhead.

When a dog started barking up at the farmyard, Dad lifted the bag and we headed for the car. A security light came on at the house, but we’d driven away before anyone saw us.

On the journey home, my brother asked Dad what my uncle would have said if he’d caught us in the field. My brother was two years older and had maybe worked out, quicker than me, that it wasn’t our uncle’s farm.

“What are you doing here?” was Dad’s answer.

He said it in a jokey way that made me and my brother laugh. I’d say if we got caught, it would have been the police asking that question, and it would be Dad, not me, who’d have had to answer. As we hadn’t been caught, we forgot about the question and headed home for a feed of chips.

I’d hear the same question from the police many times during my teens. Usually when I was out with friends in local parks, too young to get into a pub. The police seemed to be there on routine patrols, or maybe they only bothered us when they received complaints from local dog walkers, who looked at us with our long hair and band T-shirts, and thought we were devil worshippers. That isn’t a far-fetched notion, as one week it was the front-page story on the Ballymena Times. SATANISTS IN SENTRY HILL read the headline. We’d often build fires when we were cold and drunkenly sing songs, so I can understand their wrong assumptions. The paper reported that chicken bones had been found in the fire. The implication was that we had sacrificed the animal to Satan. One of our group had a part-time job in KFC, and sometimes, at the end of his shift, he would bring takeaway to eat. A more likely explanation for the chicken bones, but why let the truth get in the way of a good story?

When the police would stop us, they would ask, among other things, for our addresses. I didn’t hang out in the part of town where I lived. Mostly because, since I was into rock music and dressed accordingly, plenty of local hard men wanted to kick my head in. When the police asked what I was doing there, it seemed to carry an implication that I shouldn’t be there, because, since I was from a council estate, I shouldn’t be in a nice part of town.

On one occasion, a friend and I planned to go to the school disco as the Super Mario Brothers. Being taller, I’d be Luigi, so I put my green shirt into a sports bag and went uptown with Mario to look for dungarees. When we couldn’t find any, we went to smoke dope instead. As the wind blew strong that evening, we took shelter at the nearby bus station toilets. Now we were out of the wind, I put my green shirt on while Mario skinned up. Just at the time when we finished smoking the joint, heavy banging started on the wooden door, which we’d locked and stuck the key back into to block another key from opening it. Someone, obviously a police officer, shouted in the open window, too high and too narrow an opening for them to climb through, for us to open the door.

I didn’t even wait to see them. Mario flushed the roach while I scranned the dope, an eighth, wrapped in cellophane. It didn’t go down easily.

“What are you doing here?” one of the policemen asked.

“We came in here so I could put on my green shirt,” I said, rasping the first few words as I struggled to swallow the lump of dope.

“Why were you carrying your green shirt around in a bag?”

“Because I was going to my school disco as Luigi from the Super Mario Brothers, but I couldn’t find a pair of dungarees.”

The policeman was furious. Without access to the backstory, he likely assumed I was taking the piss, but also, without finding any dope, he had to let us go.

Another time the police asked me the question was when I got attacked by the Ahoghill Mad Dogs (Ahoghill pronounced with the—gh—as if you were clearing phlegm from your throat, not A-hog-hill). I don’t know if they thought up their nickname themselves; given that they came from Ahoghill and liked to beat up random strangers, the name suited them.

Shouting for help, I jumped into a random garden and thumped on the front door. This part of the story might damage the cool tough-guy persona I tried to cultivate with the previous anecdote, but I was two or three years younger than, and heavily outnumbered by, my attackers. The residents of the house, a young couple, made me stay outside while they called the police. When the police showed up and asked what had happened, the man from the house told them about me furiously hammering his door. I had to interrupt and tell the policeman about the Ahoghill Mad Dogs (I didn’t use the name). Luckily, the police had received several complaints about them that night as they tore up the town with their “wild-boy antics” (a quote from the local newspaper).

When the policeman took my details, he asked the question, “What are you doing here?”

When the policeman took my details, he asked the question, “What are you doing here?”

I’d developed a smart mouth by this age, but I still had enough gumption to mumble a story about being with two friends who lived in the area. We had become separated when we were attacked. I’d begun to feel the question was rhetorical. A way of saying, without saying, that I should stay in my own part of town.

London, where I live now, is different. Once you go outside of Zone 1, you find yourself in interlinked little towns, which each have their nice parts and rough parts, often only separated by a few streets. During my first year in London, myself and my wife, then girlfriend, gained a solid working geography of the various parts of the city by housesitting for a few months at a time, taking in Seven Sisters, Stoke Newington, Dalston, Islington, Putney, Ealing Broadway, and, for some reason, East Acton. During that year, the question of what are you doing here wasn’t asked, although it was always lurking at the back of my head. When would we finally find a place to settle? When would I earn a decent enough wage to pay regular rent, not the reduced holiday rates we paid for each housesit?

Lewisham ended up being where we settled, Catford at first, where we lived for a few years, and where we got our cat, who is named after the area, because she has a similar coat to the giant fiberglass sculpture on top of the Catford Centre.

In many ways, my life seems to have progressed: I wear a suit to work, so I doubt the police would be as likely to ask me what I was doing in a nice area; we own the lease on a flat in Grove Park; and we don’t have to rethink owning a cat, because of the cost of food, litter, and trips to the vet. Despite my seemingly middle-class life, I’m aware that, because I don’t come from a wealthy background, if I were to even miss one month’s wage, I’d be in difficulty. I try to save, but as the month goes on, a reason will come up for me to dip into my savings. I’ve tried to discipline myself to be stricter with my spending and expect unexpected financial necessities every month.

At the end of February, two days before payday, I was walking beside the Ornamental Canal in Wapping on my lunch break when I spotted a ten-pound note resting between some sticks in the stagnant water. Until a few years ago, seeing a tenner in water would have made me weep, but due to the introduction of plastic bank notes, I knew I could retrieve it intact. Breaking a branch off a tree, I laid flat on my stomach and nudged myself slowly off the path, one hand holding onto the chain safety barrier, which I hoped could bear my weight if I began to slide in. The thought of falling in bothered me more than someone seeing me. This was confirmed by a six-pack of joggers thundering past, each of them trying to beat their personal best (I don’t know. I don’t jog). I looked up, ready to give them my best rascal grin, but they ignored me: beating your personal best takes focus.

After retrieving the tenner, I realised it looked a bit wonky. I dried it off with a tissue and pocketed it. When it came to breaking the note in the nearby Waitrose, I tried to buy some hand sanitizer, in case I was now dosed with waterborne lurgy. The lady at the till refused to accept the note, telling me it looked fake. She even showed it to her manager, who agreed. I reckoned it was just dirty. Upon arriving back at my office, I spent the next half hour in the disabled toilets, cleaning both myself and the tenner. I took it to the local Tesco and bought a chocolate bar. I paid via the self-service till. The Tesco robot trusted the money more than the human at Waitrose. A victory for the machines.

The Tesco robot trusted the money more than the human at Waitrose. A victory for the machines.

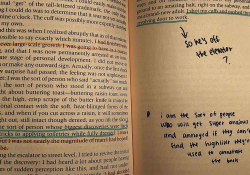

It was a Wednesday, after lunch. The working week was now closer to Friday afternoon than Monday morning. To celebrate, I ate my chocolate bar, a chocolate orange Lindt, with a cup of coffee. I stared up at the unnecessary glare of the strip lights and listened to the tick one of them constantly does, but which I manage to ignore most of the time. I thought about the paperwork I’d agreed to finalize before close of business. Paperwork I could just about understand but couldn’t care less about, that I suspected very few people would ever read or care about after signature. Payday was on Friday. In my blazer pocket, I could feel the weight of the change from the canal tenner. That would buy me lunch tomorrow, and a cheeky coffee on the way home, either tonight or tomorrow. Maybe another chocolate bar. What are you doing here? I asked myself. The answer is money. I need to pay my mortgage, my bills, my train fares, and the expenses of living a pleasant day-to-day life. Still the screen beamed at me, unflinching, as if it was it that had asked the question and was waiting for a better answer. Unlike the ropey answer my dad would have given his “brother” or my mumbled half-arsed answers to the police, under scrutiny, my answer seemed watertight, logically sound, but still, in a significant but ineffable way, it was missing something, like the hole that defines the donut. And I found myself repeating the question: What are you doing here?

The question used to have negative implications, but now, when I use it, I’m doing so to force myself to rethink things, to do a spot-check on my current situation, to ensure I’m taking care of myself. The answer isn’t as important as the thoughts involved in obtaining the answer.

London / Tallinn