Landlines

Family news still travels, but not as it once did, when families huddled together over landlines.

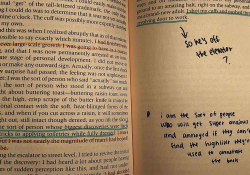

Though I was only seven, my memories are clear. It was 1960. Chubby Checker had given us the twist, Gunsmoke had given us law and order, and the country had given us JFK. I was a second-grader at Sabal Palm Elementary School in Miami. We didn’t have a big house. My sister and I shared a bedroom. My brother, being the eldest, had his own. But when Grandma came to visit, he gave up his bed and slept on a couch in the den.

Eunice was the only grandparent I ever knew. Most of the year she lived with my aunt Yetta in Brooklyn, but during the winter months she moved in with us. How lucky we were to have her! She and a younger sister had fled pogroms in Poland before the First World War. The stories were the stuff of family legend. A ship sailing into Ellis Island. Learning English at night school. Building a business from scratch. Those who remained in Europe died in the Holocaust.

Built like a block, she was five feet square, her bosom huge, her face like an overripe apple.

Built like a block, she was five feet square, her bosom huge, her face like an overripe apple. Every day she read The Forward, her finger following the print, her mouth moving as she read the Yiddish words. When she spoke on the phone, her speech was heavily accented. She overenunciated to make herself clear.

“Operator, I vant to make a person-to-person call. To Mrs. Yetta Schwartzbaum. S-C-H-W-A-R-T-Z-B-A-U-M. She’s at Dickens 65240. Yetta Schwartzbaum. Yes, I’ll vait.”

We could only afford one long-distance call a week. But a succession of people always picked up the receiver before you reached the right one. That was the beauty of person-to-person calls. The charges didn’t start until the connection was made. Meanwhile, you’d speak to uncles, cousins—whoever picked up. Then a three-way conversation would ensue between you, the operator, and the chatty relative on the other end of the line. Since it sounded like you were speaking from a tunnel, everyone shouted. Snapshots of our lives would always sneak in.

We’re heading to softball practice soon!

Dad’s nursing his knee again!

Mom’s busy dyeing her hair!

There was one day when my grandmother was particularly patient. Rumors and innuendo had trickled our way. Who knew if the gossip was fact or fiction? Finally, my aunt picked up.

“How’s by you?” Grandma threw out for openers.

I remember we were in the kitchen, the telephone cord snaking from the wall to the chair then wrapping around my grandmother’s arm. I watched her hand smooth the plastic peeling on the table. A cat swung its tail on the wall. One minute passed, then another. My God, the expense! But Grandma just sat there, nodding and clucking her tongue, her dentures going up down up down with the clucking.

Grandma just sat there, nodding and clucking her tongue, her dentures going up down up down with the clucking.

“I see,” she said. “I see.” Then she repeated my aunt Yetta word for word to make sure she got it right. My cousin Valerie, it seemed, was pregnant. Nineteen years old and three or four months along.

“I see,” repeated my grandmother. “I see. I see.”

At first we all loitered in the kitchen. But now my parents didn’t want to miss a single sound. Mom flew to the family room extension while Dad hurried to the master bedroom. Since we only had three phones, my brother, sister, and I stood stone-still and eavesdropped. We pressed our backs to the wall. Then we tried our best to stop giggling.

“I see,” said Grandma. “I see.”

For the past year, Aunt Yetta had been preparing a wedding to beat all weddings. Everything was ordered for a party that was happening in six months’ time. Valerie’s pregnancy was a catastrophe of nuclear proportions. Yetta needed advice, needed it soon, and knew just where to turn.

Watching my grandmother, I had little comprehension of the dilemma the family faced. A widow for many years, she was everyone’s go-to person. The chin cradling the phone remained steady. Her voice was sure, her composure unshaken. We waited and waited while my aunt kept talking and my grandmother kept nodding. Finally, Grandma thumped her fist on the kitchen table and made her pronouncement.

“You’ll make another vedding another time,” she said. “Valerie should get married now.”

Of course, there was never another wedding. One child followed another. Then Yetta’s younger daughter broke her mother’s heart by eloping while in college in Nebraska. But that’s another story . . .

Life, as always, grinded forward. My grandmother died when I was in high school. My father passed when I was twenty-eight. Aunt Yetta lived long enough to see both me and my children married. Even in her nineties, no one partied harder.

Even in her nineties, no one partied harder.

Then suddenly, they were gone. An entire generation had disappeared like the snap of a finger! And though the family seemed smaller, in reality it had grown. For every burial, there was a birth. For every shiva, a simcha. News would fly like a tickertape across my screen. One email in particular left me shocked.

Did you hear about the baby?

I read the message once, twice, three times. Valerie, my oldest cousin, had become a great-grandmother. A great-grandmother! My first reaction was to turn on my cell phone and punch in her number. Again, the miles separated us. I was still in Miami while she still lived in New York. But her voice, when it reached me, sounded next door. “Congratulations!” I said. I couldn’t help smiling. “I’m so happy for you!”

Then I remembered that day we huddled in the kitchen. But now there was no crackling in the background. No fading in and fading out. No yelling to make your voice heard. I searched the shadows for a familiar face. But no. No one was eavesdropping and no one was interrupting. We were astronauts stranded on two lonely planets, unanchored and disconnected, our bodies floating in the ether, our voices shooting into space.

“Mazel tov!” I told her.

Somehow it wasn’t the same.

Miami, Florida