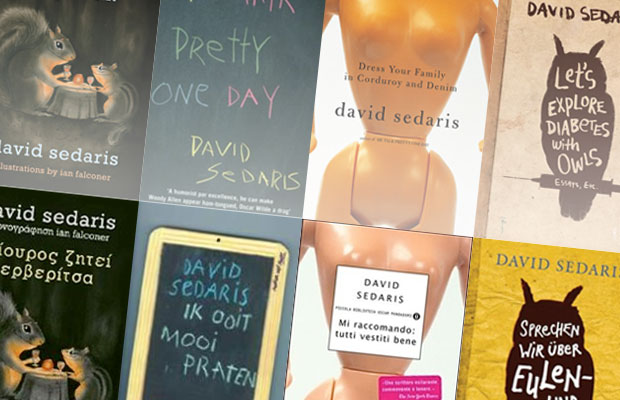

David Sedaris on His Humor in Translation

WLT: Translating humor across cultures is particularly challenging. What has surprised you most about how your translators have re-created your work in other languages?

David Sedaris: Occasionally I’ll tour another country and sit on stage as a native Italian or German or Spaniard reads a story out of whichever book I’m promoting. I follow along as best I can, thinking, This next line works in the US, but I won’t possibly get a response here. What surprises me is how often I’m wrong. It’s one thing to translate a joke, and another to translate timing, which is where a lot of my laughs come from. It’s especially difficult when the sentence structure is so very different in German, for instance, when the verb comes at the end of the sentence. In my last collection, one of the laughs was based on the way people in Toronto say “about.” The joke didn’t make sense in German, so the translator focused on another word in the sentence—“kiosk”—and moved my Canadian to French-speaking Quebec. It was a brilliant save, but nothing could salvage the ending of another essay. The laugh is based on the phrases “your trash” and “you’re trash,” and I don’t imagine it will work in anything but English.

WLT: The New York Times quotes Myrsini Gana, saying, “I feel that when the translator is laughing, the humor will manage to get across.” Do some cultures “get” your humor more readily than others?

DS: I know my books do better in some countries than others, though that might have more to do with the publisher’s willingness to promote me, and with the population’s willingness to read things written by foreigners. On the one hand you have the Germans, who will happily pick up something translated from Laotian, and on the other hand you have the Americans and the French, who, generally speaking, are pretty reluctant to read foreign books. I’m not great at it either. Whenever I tour another country I’m asked who my favorite Brazilian or Dutch or Korean writer is. In Italy my answer is Bruno Vespa. He’s a newscaster whose memoir I saw in the window of a bookstore in the Milan airport a few years ago.

“Bruno Vespa!” the journalists all say. “How do you know him?”

“Oh,” I tell them. “He’s very famous in America.”

As for countries “getting” my humor, I was surprised by how well I went over in the Philippines, and in the Netherlands. Two countries with “The” in their name.

DS: It’s axiomatic that something always gets lost in translation; what has your work gained in translation?

WLT: I think that being from the US puts me at a definite advantage when it comes to a foreign audience. American popular culture is ubiquitous. People the world over watch our sit-coms and action movies. They know what our suburban houses look like, and our police cars and our high school classrooms. As writers, Americans can be lazy in ways that, say, writers from Lithuania or Yemen cannot. What has my work gained in translation? Perhaps it underlines the feeling of foreignness I bring to most of my stories. Does that make sense?