Negotiating Four Generations of Voices (with a Little Help from Google Earth)

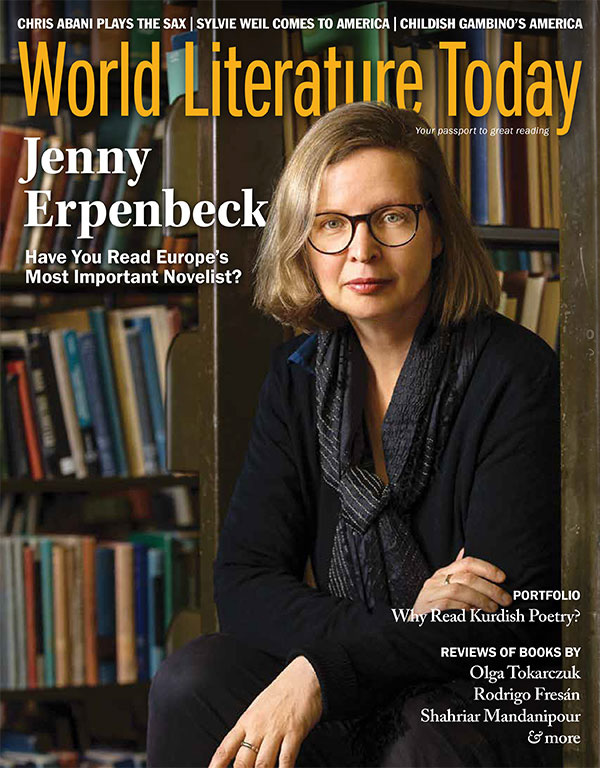

The Herring and the Saxophone (Le Hareng et le saxophone), a hybrid work by Sylvie Weil, is listed as a novel, yet just as in Tim O’Brien’s The Things We Carried and Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, the narrator’s voice carries the author’s own name. It’s written in the first person, but the narrator doesn’t fully introduce herself until chapter 5. An autobiographical work centered on family more than self—if the two can be separated. Not Weil’s own family, but her in-laws, generations of them, down to the little boy Ricky, who would one day grow up to be Eric, Sylvie’s husband.

“The Cadillac,” recounting a family gathering to celebrate a bar mitzvah, is the first chapter of this family saga that skips back and forth through time and space, without the vast arc of an epic narrative. One moment, we’re in early nineteenth-century Ukraine; then, it’s 1980 and we’re in the Bronx. The stories are at once iconic and idiosyncratic: fleeing the Russian pogroms, petitioning to acquire an anglicized name in the New World, only to see the magistrate restore its Jewish flavor, giving us a glimpse of America’s limited religious tolerance. Chapters are like the snapshots occasionally referenced by Weil, and reading the novel is like flipping back and forth through the pages of a photo album: we point at familiar faces peering out from different moments in their lives and ask, wanting to weave together the strands of this family history, “Which cousin is he again? And how was he related to that woman? Are they the ones who left Ukraine and somehow ended up in Ontario, or did they come to New York?” Weil takes us back and forth from Uman to New Rochelle, with detours to Nikolayev, Brooklyn, Toronto, Queens, Connecticut.

As the daughter-in-law, the reluctantly accepted Franco-American object of curiosity “just off the boat” from Paris when she met the man she would marry, Weil as author/narrator sits both inside and outside the family. In “The Cadillac,” we meet four generations of Shackmans. Many of the stories have been handed down to Weil by Clara, wife of Mounya of the Cadillac-with-Dagmars. Clara, the family historian, carried oral archives in her memory across time and borders, almost two centuries of lore stretching back deep into the old country.

As co-translator Catherine Zobal Dent and I work our way into this cast of characters who have already worked their way into our hearts, we are constantly negotiating voices, places, and eras. Using Google Earth, we follow the peregrinations of the various family branches from old Russia to New York. We research idioms, vocabulary, exclamations to choose words that fit time and place, personality and situation. One curious aspect of this project is that we are translating the younger generations of this family into their own language: in this chapter, for example, we understand from the French original that everyone but the elderly cousin from Toronto is speaking English. The original itself is a translation, making our work something of a reclamation.

Our method involves each of us translating a draft of a given chapter independently before we meet for our collaborative sessions. Sitting together at the screen, Catherine and I comb through our drafts one sentence at a time, discussing them, melding them in a process that spawns surprising solutions. Working together helps us keep our eye on the immediate sentence and the larger narrative, simultaneously. We’ve learned to articulate our choices to each other and, ultimately, to integrate our varying interpretations. We find it rewarding to let go of our egos and focus instead on bringing these voices alive for a new readership.

Read Palermo and Dent’s translation of Weil’s “The Cadillac” from this same issue.