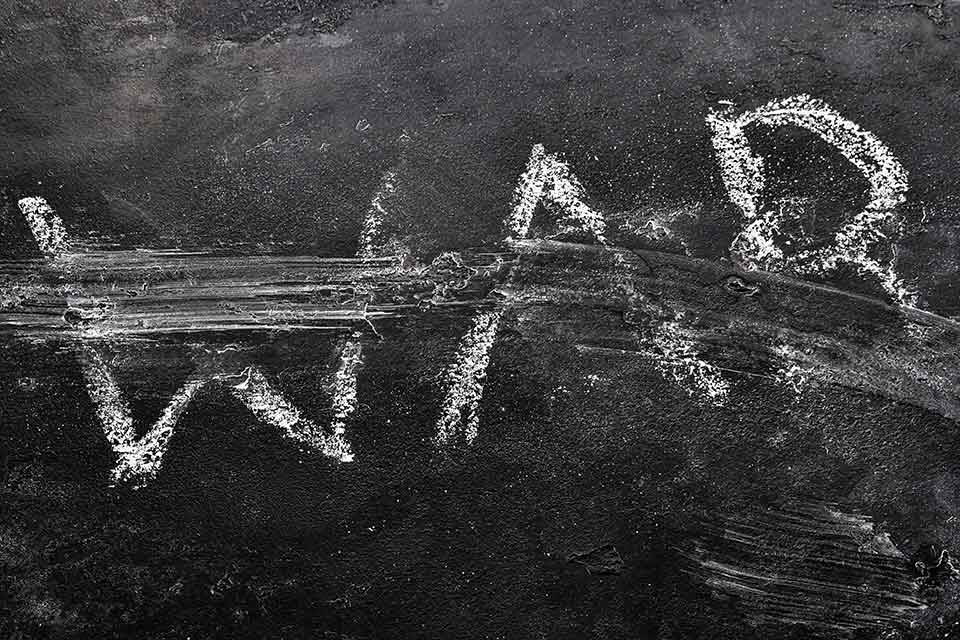

History as a Battlefield in Putin’s Russia

When Irina Flige visited the University of Oklahoma to receive the 2022 Clyde Snow Social Justice Award earlier this year, she delivered the following public lecture, based on her work with the Russian human rights network Memorial.

When Irina Flige visited the University of Oklahoma to receive the 2022 Clyde Snow Social Justice Award earlier this year, she delivered the following public lecture, based on her work with the Russian human rights network Memorial.

I’ll begin my lecture in the Russia, not of Putin, but of Gorbachev—the time of the first battle for history. I could also start in the Soviet era, when history as a scholarly discipline was annihilated, not just because of retrospective censorship and falsification, but because historical methodology was destroyed. Churchill’s old joke, that “Russia is a country with an unpredictable past,” remains relevant.

“Perestroika” was conceived by its initiators as a large-scale reform to improve “real existing socialism,” but it evolved into the complete deconstruction of the Soviet regime. By the 1980s, the decrepit communist doctrine had stopped being the basis of the “socialist order”; it was merely fulfilling decorative and ritual functions. Now, the myth of “the glorious Soviet past” had taken over the role of Soviet society’s ideological foundation. As a result, the battle for history that took place between 1986 and 1991 was not a secondary factor but perestroika’s pivotal element.

The prohibition on previously taboo historical subjects was relaxed “from above,” in early 1987, through the gaps in censorship. A huge surge of texts on history—literary and journalistic—swamped the pages of Soviet periodicals. Over the next few years something incredible happened: people’s interest in the recent past found expression in mass street action. Thousands, sometimes tens of thousands, attended rallies under the slogan “We demand the whole truth about Soviet history.” This wave gave birth to the Memorial Society—the largest civic movement of the perestroika years, with branches in almost all regions of the USSR.

The public was mostly interested in the history of Soviet state terror. This unprecedented interest in history had obvious political underpinnings—the crimes the authorities had committed cast doubt on the legitimacy of those very authorities. Hence the overall slogan of the perestroika era, “The comprehension of Soviet terror is the guarantee for permanent political, economic, cultural, and moral change,” appears justified. The Great Terror (1936–38) was identified as the quintessence of criminal state policy, followed by a struggle for the recognition of the fact that the government had been committing crimes against its people both before and after.

The mileposts marking the progress of society’s understanding of Soviet history as a chronicle of crimes emerged sequentially: the Great Terror was preceded by the collectivization of agriculture and the persecution of the kulaks (peasants deemed wealthy) in 1929–32; prior to that there were the fake political “trials” of the late 1920s; in the early 1920s the Bolsheviks persecuted the political opposition, the Church, and the critically minded intelligentsia; and finally there was the “Red Terror” during the Civil War (1918–21). The Great Terror was succeeded by the deportations of entire peoples during World War II, the mass arrests and ideological purges of the postwar years, and the persecution of dissidents from the 1960s to the 1980s.

The authorities’ ideological retreat continued for four years: they admitted to ever more crimes committed by their predecessors, until by summer 1991 it was clear that the Soviet regime had been criminal from the very beginning, which meant that its vestiges had lost all legitimacy in the present. What followed was the August Coup of 1991—an attempt by hardliners from the Communist Party to seize power—which was inspired, among other things, by the rallying cry “Hands off our glorious past!” The coup failed within three days, and reflection on the past lost its significance in public consciousness, because the issue of the party’s legitimacy had resolved itself. Public demand for historical publications disappeared, too: “Enough, we’re sick of it!” or “We know that already!”

Contemporary politics and the growing economic crisis became more important, while seventy-four years of Soviet history shifted to the periphery of public interest and remained there for the remainder of the 1990s.

Mechanically, and straight after the suppression of the August Coup, on August 23, President Yeltsin issued the order to hand over the KGB and Communist Party archives to the state. However, throughout the thirty years that followed, the majority of the KGB archives have remained under the control of its successor, the FSB. Yet, although independent researchers had only limited access to some Soviet secret service archives in the early 1990s, they could nevertheless use them—the archives were opening up. Nowadays, international researchers call this time “the great Russian archive revolution”; it was then that the most important documents initiating and regulating the NKVD’s mass-scale operations were discovered and the basis for the scholarly reflection on Soviet history as a whole was established.

However, since the mid-1990s these collections have become ever harder to access, and now secrecy has been imposed once again on the collections and documents detailing the activities of the NKVD-KGB. Most importantly, the “archival revolution” was not really noticed by the public and failed to provide the impulse for another revaluation of the Soviet past. The majority of studies on Soviet history, as well as the many thousands of archival documents made accessible to the academic community over the last decades, have never been in demand outside specialist circles and had no influence on the formation of historical consciousness. The public’s knowledge of the terror and the Gulag remains fragmented, consisting of isolated snippets of information about individual events that aren’t connected by an overall conceptual understanding.

The symptom of (and ideological basis for) the refusal of a serious confrontation of the past was a law, adopted in autumn 1991 and supported by the democratic forces in Russia, including the Memorial Society: the Law on the Rehabilitation of the Victims of Political Repression.

The adoption of this law signified a rejection of radical transformations and a refusal to regard the August Coup as a rupture of legitimacy, favoring legal succession instead. As a result, the “renewed” state accepted the legacy of the Soviet past in full. By declaring itself the legal successor of the Soviet Union, the new Russia effectively “annulled” the victory of August 1991.

In the 1990s, only limited support emerged for lustration (a mechanism that temporarily stops individuals who implemented the policies of a totalitarian regime from practicing specific professions). Galina Starovoitova, a deputy of the Russian Federation’s Supreme Council, introduced a bill “On Lustration” in December 1992 and again in March 1997. But the majority of the democratically minded public rejected this idea, and the law was never adopted.

Following brief debate, the Memorial Society also rejected lustration and didn’t insist on the creation of a judicial mechanism to evaluate the crimes of the past in legal terms. That was our greatest mistake. When they saw that the crimes once committed in the name of the state were going unpunished, the security services, and subsequently the so-called law enforcement agencies, went about committing these crimes again, first during the armed conflict in Chechnya and then all over Russia.

Historical reflection almost completely disappeared from mass consciousness. But nature abhors a vacuum: the “black hole” in the memory of the Soviet era filled up quickly, at first with a vulgar but understandable nostalgia for “the good old times.” Public demand for “the bright past” emerged from below in plain view. At the top, “political technologists,” ideologues, and propagandists added spice to this dish, turning the past not only bright but also heroic. The black hole began to fill with Soviet templates of imperial and great-power narratives, leaving out communist narratives.

The image of the Russian state as a sacrosanct Great Power from Rurik to the present day was reborn. By the late 1990s it had put down roots not only in mass culture—in entertainment literature, in journalism, and on TV—but also among the elites.

The new political elites were very keen on “new legitimacy.” The background nostalgia for the past had taken shape more or less already, now the main actor had to be brought onto the stage: the sacrosanct and eternal Great Power, regardless of its current name—Russian Empire, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, or Russian Federation.

In May 2000 the citizens of the Russian Federation elected a new president. The clear victory in the first round went to a career secret service agent: Vladimir Putin, who undoubtedly drew on the stereotypes of mass consciousness.

Two events defined the new ideological space:

On May 7, 2000, the Patriarch of all Russia, Alexy Ridiger (a former KGB agent known as “Drozdov”), blessed the accession of a colonel of the KGB, Vladimir Putin, to the Russian presidency.

And on December 20, 2000, on the “Day of the Chekist, the holiday of those working in state security, the State Duma approved the national anthem of the Russian Federation. The text was a lightly edited version of the old anthem of the USSR, with the classical triad (“Lenin–Communism–the Party”) replaced by a new one: God–Motherland–Great Power. The tune remained the same.

The words of the old-new anthem accompanied the emergence of a cult of statehood that embraced the imperial, the Soviet, and the contemporary period of Russian history in equal terms.

The words of the old-new anthem accompanied the emergence of a cult of statehood that embraced the imperial, the Soviet, and the contemporary period of Russian history in equal terms.

The public revaluation of the Soviet period, this time led by the authorities, probably began with Putin’s speech at a meeting with historians in November 2003, where the president declared that history textbooks “must foster in our young people a feeling of pride in their country.” Four years later, at the Munich Security Conference, he would openly refer to the collapse of the USSR as the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the twentieth century.”

The indifference to history that had been characteristic of the 1990s became impossible to maintain. Putinism foregrounded history almost immediately, at first in the form of a heroic mythology, intended to satisfy popular demand for the resurrection of national identity.

The main point of reference for the resurrection of historical mythology was the victory in the Great Fatherland War (the USSR, and later Russia, don’t use the term World War II; here, the war began with the German attack on the USSR on June 22, 1941). Indeed, in Soviet people’s memory, the war with Germany (1941–45) always remained the main event of the twentieth century. But even during the Soviet years this memory was imbued with humanitarian, antifascist, and distinctly anti-Stalinist tones, at least in literature, cinema, and theater. Now the memory of the war transformed into a justification of the regime: yes, there was terror, but in return we defeated Hitler. A single substitution was sufficient to achieve this effect: the memory of the war was replaced by the memory of the victory. Gradually, the remembered images of the war were cleansed of the awareness that Russia had been fighting a war against fascism as part of an antifascist coalition, and of the role of the Allies in the victory.

The memory of the war transformed into a justification of the regime: yes, there was terror, but in return we defeated Hitler.

As relations with the West kept deteriorating, this memory became purposefully suffused with anti-American and anti-European notes. Suddenly it was remembered that General Franco’s “Blue Division,” as well as volunteer formations of collaborators from occupied European countries such as France and Belgium, had participated in the Siege of Leningrad, so, it turns out, “we were fighting against all of Europe.” True, at the official level this happened only after the beginning of the full-scale war against Ukraine. And the sinister slogan “we can do it again,” meaning “we can repeat the Red Army’s victorious march across Europe” (1944–45), only appeared after the annexation of Crimea in 2014. But the cult of victory that emerged in the 2000s was nourished by imperial resentment and engendered militarist and chauvinist tendencies from the very start.

In autumn 2021, all-out state propaganda began to cast doubt on the right to existence of Russia’s neighboring states (the former Soviet republics)—not just on their right to national independence but even to cultural, ethical, and linguistic self-identification. The main target was Ukraine: it was not just progovernment journalists who made such claims but also high-ranking functionaries. In fact, this started even earlier, with the claim that the Ukrainian national resistance of the late 1940s was identical with Nazism, a highly contentious thesis. Subsequently, this thesis was extended to include any sympathies toward “ukrainianism” as such. Today, to challenge it means to “justify Nazism,” and that’s a crime.

All ideological underpinnings of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, starting with the annexation of Crimea and the hybrid war in Donbass in 2014, and culminating in the invasion of February 24, 2022, are sustained by pseudohistorical arguments. History has once again become something to be manipulated in order to justify aggression and consolidate a fascist dictatorship.

As for the memory of Soviet state terror, the new myth has managed to integrate it completely. Of course, it’s been marginalized. Yet unlike in Soviet times, it’s not forbidden; moreover, it occupies a clearly defined place within state mythology as the memory of the victims. The victims are victims not of the crimes the authorities committed against their fellow citizens but a sacral sacrifice brought at the altar of the Fatherland. The terror is what made the people’s victories and achievements possible. The victims exist, but the crimes—and the criminals—do not. It’s pointless to look for a rationale within Putinist mythology—there isn’t any, and nobody needs one anyway. The monuments to Stalin, which appeared in Russian towns throughout the 2010s, calmly coexist with memorial cemeteries for the victims of repression.

However, the second update to the Soviet past within thirty-five years, this time provoked by Putinism, has acquired new and unexpected aspects. What has kicked in is a specific trait of historical memory: when history is not reflected upon, it inevitably turns into a legacy for the present and into a key component of sociopolitical life. The memory of the terror is alive and actively present in public consciousness.

It’s become impossible to talk about the terror and the Gulag in the past tense—they constitute prolonged historical reality. In 2011 oppositional tendencies increased sharply, and mass protests erupted in many cities, mostly in reaction to vote rigging during the elections. In 2012 the police began to brutally disperse the protests; those arrested were accused of “inciting disorder” and imprisoned. Since 2014, the beginning of Russian aggression toward Ukraine, society has been developing its own “anti-Putin” demands for a revaluation of Soviet history.

What emerged in response was something akin to a united front of human rights organizations, which defend those under arrest and organize support for political prisoners, etc. Simultaneously, opposition activists, especially younger ones, are showing a noticeably greater interest in history.

The current demand for reflection on the practices of Soviet terror comes from the oppositional stratum of Russian society; it’s above all an attempt to comprehend today’s political reality and the regime’s current crimes. This demand emerged during the struggle for the liberation of political prisoners and protests against torture and violence.

The network of organizations that make up the Memorial Society is the addressee of two separate demands: for human rights support and for reflection of current events in the light of history. Memorial is once more a visible component of the country’s intellectual and political landscape, no longer as a reference point for the preservation of historical memory but also as a center that consolidates the opposition, forced from the field of politics.

In the mid-2010s, civil war broke out between different forms of memory. The creators of the new state ideology don’t intend to retreat. They are energetic and aggressive, and they have huge resources in the fields of propaganda, education, and legislation at their disposal. Their ambitions are boundless: they are firmly resolved to restore the state’s control over history. This is a real war, with victims, prisoners, and “purges” of newly acquired territories. Simultaneously, interest in the experience of Soviet-era resistance—mostly the dissidents of the 1960s–1980s—has reached new heights.

In the mid-2010s, civil war broke out between different forms of memory.

However, the archaic myths of Putinism, the political murders, torture, arrests, and persecution of the opposition, the falsification of criminal cases against opposition activists and protesters, have refreshed the memory of Soviet terror. Today the focus is on the issue of state violence as such and on how people have resisted it yesterday and today. Tens of thousands of people participate in the “reading of the names” (a new rite of memory for the victims of repression that emerged ten or twelve years ago). Sites of memory, such as the Solovetsky Stones in Moscow and Petersburg or the Sandormokh wasteland in Karelia, have become sites where people express their solidarity with political prisoners “of all times and all peoples”—first and foremost with the new prisoners of today’s regime.

In 2021 heavy artillery entered the battlefield of history: the FSB, the Public Prosecutor’s Office, and the Investigative Committee. The events enfolding around the Memorial Society illustrate how it happened. Before 2021, Putin’s regime waged a proxy war with Memorial, using pseudohistorical propaganda organizations (Sergei Kurginian’s “The Essence of Time,” Aleksandr Dyukov’s Historical Memory Foundation, Vladimir Medinsky’s Russian Military History Society) as well as thugs from far-right organizations (the “National Liberation Movement,” the “South-Eastern Radical Coalition” [SERB]). But in autumn 2021, the authorities stopped hiding behind the GONGOs (government-sponsored nongovernmental organizations) and set in motion first the administration and then the judiciary. (It’s worth mentioning that back in 2015, the Ministry of Justice had declared several organizations within the Memorial network “foreign agents,” impeding their day-to-day activities.)

The “International Memorial Society,” uniting the Memorial networks in Russia and Europe, has been disbanded by the courts. During the last few weeks, the authorities searched and ransacked the offices of Memorial in Moscow. They opened a criminal case because of publications that purportedly “rehabilitate Nazism.” A different case accuses Oleg Orlov, the director of Memorial’s human rights operation, of “circulating fake information about the activities of the Russian army during the Special Military Operation”—he is being prosecuted for antiwar protests.

Today’s main task for those of us who work with the memory of the terror is to work on our mistakes: where did we get it wrong? Because after the war, after the fall of Putin’s regime, we have to be prepared to work with the memory of today’s crimes and the current humanitarian catastrophe, and we must not repeat the mistakes we made the first time around.

Translation from the Russian

The Clyde Snow Social Justice Award

In April 2023 Irina Flige visited the University of Oklahoma campus to receive the 2022 Clyde Snow Social Justice Award. The award is named after Dr. Clyde Snow (1928–2014), a prominent Oklahoman and an internationally known anthropologist and forensic scientist who committed his knowledge and skills to the pursuit of social justice through the recovery and identification of victims of human rights abuses around the world.

Flige (b. 1960) is one of the founders and the longtime director of Russia’s Research and Information Center “Memorial,” the human rights network that has its primary branch in St. Petersburg. She was also a longtime board member of Memorial International in Moscow, which the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation ordered closed in 2021 as part of a larger crackdown on civil society and human rights organizations. In 2022 Russia’s Memorial network as a whole shared the Nobel Peace Prize with a human rights advocate from Belarus and a Ukrainian human rights organization.

In addition to her work with Memorial, Flige is the world’s leading expert on what she terms the Gulag “necropolis”: the network of mass and individual graves that resulted from the waves of repression that convulsed Soviet society during the Stalin period. Source: The WGS Center for Social Justice | www.ou.edu/cas/csj

Read an web-exclusive interview with Flige conducted while she visited the University of Oklahoma to receive the Clyde Snow Social Justice Award.